The following is respectfully quoted from “Reborn in the West” by Vicki Mackenzie, recounting the life of Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo:

After she felt she could go no further with this particular meditation she prayed for guidance on what to do next. She had another dream which told her to examine all the probabilities that could come out of her life.

‘I use to imagine all these white picket fence scenarios–the typical Western dream,’ she continued. ‘I did these meditations where I would suppose my husband and I were always happy–like in the commercials where you run laughing towards each other through the wheat fields. And my son would grow up to be doctor–he’d be wealthy and loving. And I would have other sons and daughters and they would grow up to be successful and happy too. Then I asked myself: supposing I attained every material dream a woman could have in America, then what?

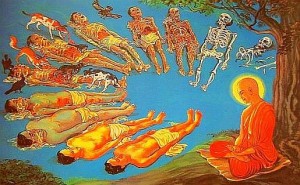

‘I meditated on that. It was turning the mind. I saw that these things, these dreams and hopes were pointless. Where did it lead? After all this, you die. I began to see that there was no future in these kind of endeavors. Even if I were to be totally happy in the world and invested all my time and money in it, there was ultimately no point. I might get the admiration of my peers, and all the riches I could dream of, then I would die. Then what?’

What she was describing was the basic Buddhist meditation on death and impermanence that I myself had done in Kopan back in 1976.

‘I remember meditating on this, holding my son in my arms and thinking how I wanted to protect this little being and feeling I would do anything for him. I remember thinking “I absolutely commit myself to making you safe.” And then I realized in my meditation that I couldn’t make that commitment. If my son were to become terribly ill and die there would be nothing I could do about it. I couldn’t follow him into the after-death experience. I realized I was lying to my baby,’ she said.

This relentless scrutiny of her life, the various ways it could go and the inevitable outcome in death was to have a critical impact on her life. From then on she turned her back on worldly pursuits. In Buddhist terms she had achieved renunciation–the lack of fascination with the ups and downs, the dramas and the joys, of mundane existence. It is said that only when you achieve renunciation do you truly step on to the spiritual path, because only then do you stop believing that following the goals of material existence is the way to happiness.

My heart swells with love for you, Jestunma, and I am filled with awe and gratitude.

Thank you my dear teacher