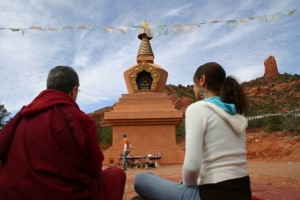

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love Series

In the West we have a certain context through which we understand. There’s a certain karmic format that we all participate in; our thoughts are shaped a certain way. When we are children and form our ideas we all receive, individually and collectively, a certain kind of input. These things have a very important influence on us. So the way a Westerner and an Easterner might approach the Buddha’s teaching is probably slightly different.

All of the cultures that practice Buddhism on a grand scale practice them from birth. The basic ideas of the Buddha’s teachings permeate the entire culture. But that’s not so with ours. In fact, there are some ideas that we have been brought up with that seem to be contradictory to the Buddha’s teaching. From this point of view, teachings of the Buddha have to be presented in a way that we can understand that while they seem to be contradictory to what we have learned, in fact they are not.

There is a universal truth being presented that isn’t contradicted by our culture, although the language and understanding is different. If something is a universal truth, then it must be true wherever it is, or it isn’t true at all. So what we’re looking for is a way to explain some of the basic thoughts to those that have never practiced Buddhism and haven’t heard any of these teachings before.

Compassion is a foundational thought that occurs again and again in the Buddha’s teaching. But Westerners define compassion differently than Easterners, because Western ideas surrounding the concept of suffering are different than Eastern ideas. From a Westerner’s point of view, we tend to think of compassion as meaning you feel sorry for somebody. It seems to be understood on a relatively superficial and ordinary level. If I say to you such and such is a compassionate person, you would think, “Oh probably he or she is kind. They probably speak nicely. They probably feed hungry people and put seed out for birds.”

Now, perhaps for a people or culture more schooled in the Buddhist teaching, when you say compassion or Bodhicitta, levels and levels of understanding occur within the mind simultaneously, and a more profound understanding takes place. So although as Westerners we might think it would be valuable to be compassionate, if we understood the full implications of compassion on the many different levels that it exists, we would think compassion is not only desirable, but essential. There is no life without compassion.

One of the things I would like to do is deepen our understanding of compassion so that it becomes essential. If it doesn’t become essential, we have the potential at any given moment to choose to be compassionate or not. We can fall into being not compassionate. We can accidentally forget to be compassionate. All these different things can happen. You know that this is true, if you look at your life: if you remember and are mindful, you sometimes do a fairly good job. Then if you go into your natural habits, or become tired, have indigestion or PMS or whatever, you may forget and not be mindful of compassion.

If we had a deeper understanding of compassion it would be part of our foundation and there would be no choice, in the same way that there’s no choice about breathing. You would never think, “Well, I’m in a good mood now, I’ll breathe,” or, “Well breathing is okay now because I’m relaxed,” or, “I can manage that now.” That doesn’t happen because you know that to breathe is to live. If we understood that compassion is as much a part of our being and as essential to our existence as breathing, then there would be less choice about it. It would more naturally and gracefully be part of our mind state. In order for that to happen, we have to understand what compassion really means, and we have to understand the nature of suffering.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved