A Teaching by Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

In Vajrayana Buddhism (literally the Diamond Vehicle), which is the form of Buddhism preserved in Tibet and Mongolia and the one followed in my temple, one of the foundational teachings is the understanding and practice of compassion. I personally find that a religious philosophy based on selfless compassion is deeply satisfying, and I believe that it strikes a chord with many Americans.

However, although there are many people who embrace the idea of compassion as love and a deep caring for others, they do not realize that to actualize the mind of Great Awakening requires a deliberate and disciplined path. Human beings are not born with great compassion automatically realized. Thus, the Diamond Path can be described as a technology for spiritual development.

From the Buddhist point of view, there are primarily two ways to approach compassion: aspirational compassion and practical compassion. When one begins to practice on the Diamond Path, one begins straightaway to make wishing prayers, cultivating the idea of being of benefit to beings who are revolving helplessly through cycles of existence. This is aspirational compassion.

Every practice in which we engage, every teaching we hear, every empowerment we receive, every prayer we chant, can all be dedicated to the liberation of all beings from all forms of suffering.

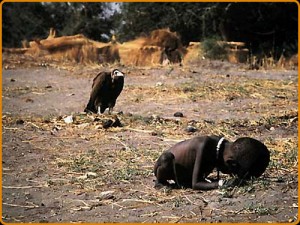

Thus, aspirational compassion is practiced in the beginning by many repetitions of wishing prayers. These prayers are meant to benefit beings through developing the sincere desire to utilize all one’s activities — from the mundane to the sublime — as a means of eliminating the causes of suffering in all its forms. One prays for the cessation of war, poverty, sickness, death and rebirth, loneliness, hatred, greed and ignorance. One adopts a posture of pure intention based on the idea that every portion of this life, as well as future incarnations yet to come, might somehow be useful to sentient beings.

As an example of this type of wishing prayer, I will paraphrase a famous practice:

If there is a need for nourishment, let me return as food. If there is a need for shade, let me be a tree. If there is a need for shelter, let me be a house. If there is a need to cross over, let me be a bridge. If there is sickness, may I manifest as the doctor, the medicine and the nurse who restore health. May I be land for those requiring it, a lamp for those in darkness, a home for the homeless, and a servant to the world.

While this may sound very kind and loving, the intention here goes far deeper than the apparent words because one must strive to be of benefit not only to fulfill the immediate needs of beings, but also to bring future benefit. Providing things such as food, housing, and medicine bring about benefit, of course, and this type of kindness is profoundly virtuous. We should all strive to meet the needs of others in just these ways. Yet, from a Buddhist perspective, being able to practice only this type of compassion does not bring ultimate benefit. For instance, if it were possible to feed an entire nation or perhaps even the world and completely eliminate hunger and hopelessness, we still would not be solving the root of the problem.

According to the Buddha, there is no condition or circumstance without a cause. Just as the fruit does not manifest without first appearing on a tree, which came from a seed, neither does any circumstance, good or bad, in which we find ourselves manifest without a cause. These causes may not be found in this life only, but may come from previous lifetimes.

It is not possible for people to be born randomly into difficult circumstance or to suddenly experience the onset of tremendous suffering and upheaval. These events are always the result of a tapestry of cause-and-effect relationships (karma) woven around the delusion involving the definition and maintenance of an ego. Thus, to solve the immediate needs of beings may bring some relief, but it does not guarantee that they will not experience great difficulty in the future, because it does not break the continuum of cause and effect that ripens unexpectedly and constantly. This continuum originates from the belief in an ego self and the desire that results from that belief. It is through the pacification of desire that one can begin to transform one’s karma. When the delusion of ego begins to dissolve, karma also begins to dissolve. But if the mindstream is not purified of the karma of suffering, the potential for suffering remains.

We were raised to believe that reality can be manipulated. Our libraries are filled with books of great American success stories. These tend to be about material successes. But the spiritual aspirant must ask: Will this success last? Even if it lasts for an entire life, will it survive death? If we had the power to bring peace to the world, to disarm nations and maintain order and harmony, would that peace last beyond our lifetime? Many leaders have exhausted their lives forging great nations and empires only to have them destroyed shortly after their deaths.

To provide beings with the ultimate benefit of freedom from all suffering, one must apply the ultimate technology. The aspiration to be of benefit to beings, the cultivation of pure intention, the continued observance of human kindness, the making of wishing prayers, and constantly hoping from the core of one’s mind and heart to be of lasting benefit to others, are practices to develop compassion. Yet at some point the ultimate step must be taken. This begins with the realization that temporary happiness is not enough, that feeding and clothing people, along with other acts of kindness, are not enough. These things cannot undo the certainty of death, which puts people beyond our reach. How can we follow them into future incarnations to ensure their safety?

There is only one way to cease the ripening of the seeds of suffering: enlightenment, which dissolves the belief in ego, pacifies all cause-and-effect relationships or karma, and reveals one’s true primordial nature. The Diamond Path utilizes many techniques to purify the five senses and the mindstream itself. When these practices are engaged in, not only for one’s own benefit but also to purify the karma and suffering of others, the practical aspect of the Awakening Mind — practical compassion — is engaged. This is “practical” because it is the technology to completely rid oneself and others of the causes for suffering. Buddhists view this type of compassion as the act of ultimate kindness.

While ordinary kindness is a valid undertaking and should be part of the activity of every spiritual aspirant, one must address the question of ultimate benefit, of eliminating suffering at its roots.

We should take to heart what the great Indian Buddhist Shantideva wrote a thousand years ago. “May I act as the mighty earth or like the free and open skies to support and provide the space whereby I and all others may grow. Until every being afflicted by pain has reached to nirvana’s shores, may I serve only as a condition that encourages progress and joy.”

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo