An excerpt from the Mindfulness workshop given by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo in 1999

In practicing bodhicitta in a mindful and discriminating way, one has to understand first of all the faults of samsaric existence. One has to understand the basic logic if it. If we are giving rise to the aspiration to be of benefit to beings, it only makes sense if we understand why and what the connecting factors are. Otherwise it is just acting.

One of the greatest obstacles I’ve seen, is the current pop religion culture that says, “Everything is perfect; the world is perfect.” So many people are into the idea of seeking happiness that on some level they must realize that there is suffering, because they’re trying to cover up that suffering. They’re trying to affirm it away by saying that suffering doesn’t exist. They tell themselves everything is light and love and suffering doesn’t exist and that’s wonderful, and so the world is a great place. We don’t have to practice compassion, because everything is already blessed and very holy. The world is perfect. Can you hear the superficiality in that? What you need to hear next is what’s really going on in the world because if you’re in that mind state, you haven’t been watching, you haven’t seen.

There is such an extraordinary amount of suffering in all the realms of cyclic existence. In this world alone, just look at the human condition: the extraordinary, unconscionable suffering. How can you look at these people marching out of Kosovo and think that’s perfect? How can you watch children and innocent civilians being torn up, with no understanding as to how this could have happened to them? They are modern people like us. How can you look at that and say everything is love and light; that everything is perfect?

If you’ve had the good fortune of knowing one person throughout the course of your life, think of all the different ages and stages they’ve gone through. Watch what it’s like to be a child and to go through all the struggles that children go through? It’s tough being a child. They don’t really understand what’s happening to them. They don’t really understand why it is when certain things happen, other things happen. It’s tough being a child. That little brain is forming. It doesn’t work in its entirety yet. And then watch that person grow up to be a teenager. It’s tough being a teenager. It’s awful being a teenager. I remember being a teenager. I don’t think there are words for that! You have all these feelings and your body is all grown up and your head is still childish and nothing works. And then you grow up, and suddenly you’re supposed to be an adult. You don’t feel any different, though, than you did when you were a teenager or a child. You still feel like you don’t understand diddly-squat, and yet suddenly, because you have a child maybe, you’re supposed to be an adult. You think, “Wow, I’ve waited all my life to be an adult. This is great. Now I can vote. I can drink.” Yeah, you can also get up early every morning and go to work. You can also work every single day. You can also have very little fun.

Do you remember what it was like when you were just trying to build your life? There’s an obsession with that. You think, “Ooh, I’ve just got to do this. If I don’t do this, I’ll never be happy.” All that reactive delusion kind of beats you up. Then, when you get to the point of maturity and you realize that not all the things you thought really mattered actually matter, there’s a little spaciousness. Maybe you have a pause that lets you know that maybe now it’s time to relax a little bit about getting all these material things lined up; maybe now it’s time to stop and smell the roses and then even beyond that, plan for your maturity. Maybe you think, “I should think about my death. I should think about how to take care of my children.” So you get this glorious moment of thinking, “Yeah, okay. I’m pretty stable now. I’ve got a car, got a house, got some kids, so things are okay.” You have about five minutes of that before everything you have goes south, and I mean the body. This thing that we put so much energy into shining up and growing up and waiting until it is matured, and then everything you have from the waist up is now from the waist down.

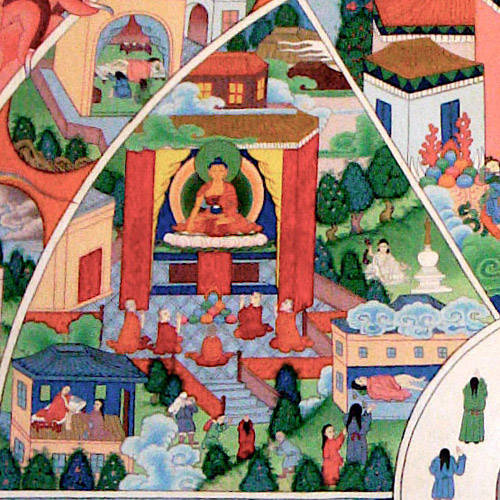

As Buddhists we are required to study these images of a young woman or a young man, middle-aged or mature and then older, and then see that this is the same person. Understanding what that’s all about is the key. For us to not wander through life with everything happening to us unexpectedly. That’s the most amazing thing about us. Everyone around us gets old; everyone we see gets old; we’ve got old people everywhere, but it’s always a surprise when it happens to us. How can we possibly go through life in any meaningful way when it constantly surprises us? Instead, what we need to do is to really study the conditions that we are involved with and do so truthfully and honestly.

In the practice of bodhicitta, the first things that we can understand are the faults of cyclic existence. Cyclic existence is impossible. It’s ridiculous. It’s not only flawed and faulted, it’s a real pain in the neck. The amazing thing about cyclic existence is that no matter what you do in the material realm, in the realm of experiences, if it arises from samsara and is within the realm of samsara, it’s all going to come to nothing because anything that you accumulate, build, or create, you lose when you die. You won’t be able to take that with you.

The saddest thing and the thing that we have compassion about and try to become mindful about, is watching someone who is no different from us, wanting to be happy just like we do; spend all of their time pulling stuff together, accumulating or not accumulating, setting up their little gigs, their little power things, all their little personality dramas. We watch people that are so entrenched and lost in that, and generally, before we’ve had any training, we’d think that was normal. But having had training, we think, “Oh, maybe that’s not so good. Maybe that’s not the way to go.” We might judge that person as being superficial. We might have a lot of judgment about that person. But in order to be truly discriminating and mindful and to actually benefit our practice, we should be saying, “Yes, that’s what it’s like here. That is the fault of cyclic existence,” and feel compassion for them.

Creating mindfulness in the arena of practicing bodhicitta is like that. We have to constantly caution ourselves not to simply go down the road in the way that we ordinarily do, but instead, to be in a state of recognition and awareness. When we see ourselves act in a superficial manner, just going through the motions of life thinking, “Oh, I’ve got to have this money or this power or this fame or this fortune or this car or this family or this whatever” — instead of judging these terrible faults in ourselves or in each other, simply say, “This is the fault of cyclic existence.” Rather than saying that person is superficial or that person is lost or that person is damned, we ought to say, “What a fabulous opportunity to study the faults of cyclic existence.” You should look at that person, and say, “Oh, I’m so sorry, because that’s how it is here. What can I do to help? How can I benefit sentient beings so that it is no longer the case?” It increases your bodhicitta practice rather than taking it down by judging others. To say, “They’re so material; they’re just about money” or, “I’m just about money, I’m just about material things.” is not beneficial because you are not contributing to mindfulness; you are contributing to judgment. Can you see the difference? You are not contributing to a state of recognition. You’re only recognizing appearances. Big deal! Dogs can do that! Do something dogs can’t do.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo