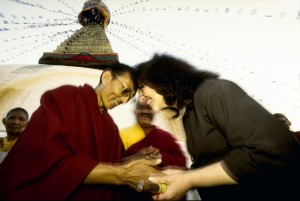

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “The Lama Never Leaves”

What I would like to talk about today is our opportunity right here. We have a tremendous opportunity. Whenever lamas come to this temple, they say, “This is a living jewel in America.” That’s what they say. They say that this temple is a living jewel; that it’s the real thing. They use phrases like that. This is really Dharma; this is the right stuff. They also say that we have all the objects of support here. We don’t really know what that means, but we’re glad we have it. So I’ll tell you.

We have these visible objects of support, meaning that, for instance, right in front of us, we have the cosmological display of the mind of enlightenment. That is the sand mandala that remains there. His Holiness [Penor Rinpoche] allowed it to remain so that we can have with us that display and take refuge and meditate and be mindful of that and to learn. It is the very display of the mind of enlightenment. Each object in the mandala has specific meaning and so we are delighted to have this.

Then we also have beautiful statues. The statues are not specifically the objects of refuge, but they are physical supports for the objects of refuge. In other words, our eyes are allowed to rest on these objects. Our eyes are allowed to, for instance, study the hand positions, the objects that are being held and to learn from them the meaning of the objects, because each of the objects that any of the statues hold has to do with a quality of the Enlightened Buddha. So each and every object that is held has to do with quality or maybe in some cases activity, like in the case of, statue of Mahakala that may hold a great lasso. He lassoes the negativity and pacifies it. So it has to do with the qualities and the activities of the enlightened mind. We ourselves use the same images in our practice so that we can practice these very qualities and these very activities. For instance, if we generate ourselves as Manjushri, we then are holding the sword that cuts the darkness of ignorance.

Then we have an altar where we can make many offerings. We try to make the offerings as extensive and as beautiful and as exceptional as possible. Maybe we wouldn’t think to have so many flowers in our own home. Maybe we wouldn’t think to offer so many bowls of rice. Why would you want to have so much rice or so much water or so many candles? Why would you put so many sweets and delicacies and things on the cabinets like that? You wouldn’t do that in your own home. And that reminds you that here we are in this amazing temple with these objects of refuge and we are making many offerings. It reminds us that these are offerings; and we again, in some subtle way, offer them when we see them being offered that way. So that is a condition by which we can practice virtue and gather merit. Anytime we make an offering to an altar, there is a great deal of merit in that, and our minds become more purified and more virtuous. And so that is a cause for happiness.

Here are the statues. They’re not just ordinary statues, that is to say, lumps that are formed to look like the Buddha. Each of them has been empowered, and there are specific mantras that are within each one of them. Usually there are mantras that are general and there are mantras that are specific to the deity. Inside there is a central channel, as though it were a living deity where the central channel is the beginning emanation of the deity’s form. Inside each and every one of them is a a copper tube, or maybe it can be wood, like the spine of the deity. And so in every single one, there are profound prayers and many offerings. Some of them have relics in them. Some of them have jewels, no really fabulous diamonds, so there’s no sense stealing any of them. We actually had somebody in Poolesville steal a ring from the stupa once and he lost his finger—the finger with the ring on it— so he returned the ring. You don’t want to do that. You want to think of whatever offerings are in there as being the very jewel of enlightenment and that that is something precious.

By the lama’s power, each and every statue is empowered; that is to say, the lama generates the deity and invites the deity to remain. And so the deity actually remains as this statue. That doesn’t mean Guru Rinpoche is here and not there, or there and not here. It doesn’t mean that, but it does mean that these statues should be treated like living Buddhas. And that is the cause for great merit. There are many practices that are done, particularly during Losar [Tibetan new year], where we take a statue of the Buddha and we carefully wash it and say many prayers. We say, “Although the Buddha does not need washing, by this washing may all sentient beings be cleansed of the suffering of non-virtue.” And so the cleansing of the Buddha is a tremendous virtuous offering to make, you know, to cleanse the Buddha with saffron water and to offer the Buddha a cloak. Although the Buddha is never cold, one would offer that cloak in the hopes that, “By this offering may all sentient beings be free of the suffering of want, of nakedness or of cold, or of not having any clothing, and may they be clothed eventually with the gorgeous array of Dharma.” So we make these kinds of wishing prayers.

When we make these wishing prayers for others, we are making them for ourselves, as well. In fact, there’s almost no need to include ourselves in those prayers, although we certainly may, and many of the prayers have words like that, “May I and all beings…,” or “May all beings and myself included…,” like that. But whenever we make prayers for the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings, for the end of their suffering, for their continued advance upon the path, then surely you must know that by the merit of that, we also are accumulating a great deal of merit to do that very same thing. So that merit is ours as well. In fact, when you accomplish something meritorious, by dedicating that merit, the minute you dedicate it, you can no longer burn it up in an adverse way. It’s like you put it in the bank. You can’t spend it anymore. And even though it goes to benefit all sentient beings, it’s still in your bank. It’s awful we have to explain it that way, but ours is a materialistic society, and that’s how we understand things.

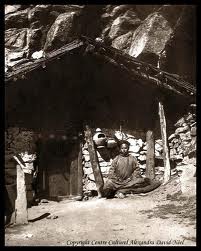

So whenever we commit some kind of virtuous act, we should immediately think, “This I dedicate to the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings.” Whenever we go round and round the stupas—even trying to relieve our own suffering, which many of us do and should really, because we have had cures around the Stupas—we have had amazing turn-arounds in people’s mental states, their habitual tendencies, even mental illness. We’ve had amazing events come about through circumambulating the stupas and making many prayers. The minute we do that, we should absolutely dedicate that to the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings.

When we pray for our own health, we should not do so without praying for the health of others as well. When we pray for our own happiness, we should think, “Oh, here I am in this land of great fortune; and here I am securely, hopefully, upon the path, and here I am in front of the objects of refuge and yet I can be so miserable. If this is possible, then how much more miserable than I am must other sentient beings be—those who have no food, who have no home, who are in war, who experience earth changes or tsunami or terrible events. Here I am in comfort and I am suffering, then therefore I pray that their suffering will cease also.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved