A Teaching by Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

When one begins to understand some of the ideas that are presented in Dharma, one realizes that the goal that we are engaged in “moving toward,” if you’ll forgive that bad choice of words, is actually Buddha Nature itself. We tend to consider that the path is like a thing that goes from here to there, like a movement toward, and it’s very hard not to conceptualize it in that way. But, in fact, when one practices Dharma, the ability to practice Dharma is actually based on the understanding of the innate Nature. If we did not have within us right now the seed of Enlightenment, if we did not have within us the potential to actualize ourselves as the Buddha, there would be no point of practice. The very basis for practice is that understanding. This is what the Buddha himself taught – that all sentient beings have within them the seed of Buddha Nature, and that Nature is their true Nature, in fact. However, they have not awakened to that Nature and so, in order awaken to that Nature, one engages in the path. The path should not be considered a ‘thing,’ a straight line that connects from here to there. The path should be understood as a method that one uses in order to awaken to that Nature which is already our Nature; which is complete, unchanging, and will never get any bigger or any smaller. One should understand that Dharma is actually an activity that is meant to awaken that potential. But the ultimate goal that one wishes for when one engages in Dharma, is, of course, Enlightenment itself. Now, what is Enlightenment? One understands that Enlightenment is actually the awakening to the Primordial Wisdom Nature, the awakening to the Buddha nature.

The Buddha never said that he was different from anyone else. He said simply, “I am awake.” He is indicating that he has awakened to the fullness of his own Nature and is able to abide spontaneously in that awakened state without any interruption or impediment. So, from that perspective, the basis of practice, the basis of the path itself is exactly the same as the goal. They are indistinguishable from one another. The path that one uses in order to achieve the goal is also indistinguishable from the basis, which is the Buddha Nature, and is also indistinguishable from the goal, which is the Buddha Nature. So, these three things, the basis, the method and the goal are indistinguishable from one another.

For us, however, it does not appear to be so, simply because of the way our minds work, involved in discursive thought as they are. We distinguish between what is potential and movement. We distinguish between movement and the goal. But in truth, you cannot distinguish between these three. If the basis for practice is the same as the goal, then anything in which you engage in order to achieve that awakening to your own Nature, must also be indistinguishable from your own Nature. The path, then, or the method, is not separate from the Buddha Nature.

Now, where we run into trouble is when we make our Dharma practice an outward movement that goes somewhere. When we do our practice, we project that there is going to be a certain result. That very subtle concept prevents the practice from doing all that it can do to remove obstacles from our own perception, because we cling to the idea of here-ness and there-ness, of such-ness and thus-ness, and in doing so, we cling to the idea of self. It’s very hard to understand that subtle difference, but that subtle difference is very important. If we did not view our Dharma practice as a subject, object, thing or as a linear movement in some way, we would more easily understand that the goal is the un-moveable, unchangeable, fully complete and spontaneously realized Nature itself, which is already present. The potential for the realization of that Nature would be much stronger in our practice, in terms of taking responsibility for our situation and utilizing our practice to its fullest capacity.

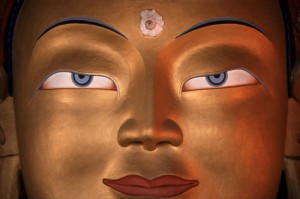

In order for us to consider our Dharma practice, or even the ability to listen to teachings, as a movement that ‘goes somewhere’ we have to be considering it in a very superficial way. But if the practice is understood as a natural and spontaneous manifestation, arising from the Buddha Nature that is our Nature, then the practice becomes less materialistic and more meaningful in a very profound way. In the same way, if we are in an ordinary environment and an ordinary teacher comes before us, we don’t respond as we would if the Buddha himself, with all the signs and marks, were sitting in front of us. If the Buddha appeared, we would respond with, “Whoa! Whoa! This is important! Something is happening here. The Buddha is here!” In truth, we should respond that same way to our own simple practice because that practice is indistinguishable from the Buddha Nature itself. The Buddha is here. But you see, the impact is different. Why the impact is different is because of the way that we consider and understand what we’re doing.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo