The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo given at Kunzang Palyul Choling in Maryland:

phowa

Birth and Generation Stage Practice

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

Should we pass through the bardo where we meet the wrathful deities, and still we have not been liberated, we have not exited, then we will continue on in the bardo. Here is a very interesting thing I want to tie together with all of you at this time. You may have noticed that in practicing Vajrayana there are certain patterns that appear again and again and again. And those patterns are that in generation stage teaching, again, as I explained to you yesterday, by seeing oneself the way we see ourselves now but lightly and in an illusory way, we sort of lighten up on the way we see ourselves. We do that by dissolving self nature into shunyata, and meditating temporarily, realizing that self nature and emptiness are indistinguishable from one another. We practice meditating on emptiness. This is before we accomplish generation stage practice. Then there is the reemergence or the reappearance. Birth. The dissolution into emptiness is the disappearance or death, the ordinary death. The disappearance of the physical self when you are beginning to practice generation stage teachings is the same as and fits in with the pattern of death. That is, ordinary death. Do you see what I am saying?

The meditation on emptiness is the dissolving of all of the elements; and the meditation on the black or clear path, or the appearance of the primordial wisdom nature as it happens in the bardo is, in generation stage practice, practiced by the meditation on shunyata. Then the reappearance, which is the reappearance as self nature or reappearance as the deity, often reappearing as the seed syllable first and then reappearing as the deity itself is rebirth. Literally, when we are practicing generation stage teaching we are practicing how to die and be reborn—how to die as ordinary and be reborn as supreme or extraordinary or enlightened. As the miraculous rebirth. This is what we are practicing; and that is the logic of Vajrayana practice and of generation stage teaching.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

The Blessings of the Wrathful Display

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

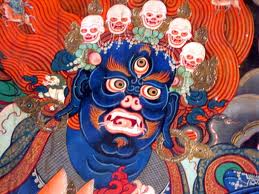

This is not separate from you when you see the Buddhas in their wrathful state. Do you really think that it is separate from you, that it is unfamiliar to you, that you yourself are not like that and should run? In fact, this is an indication to you, and a display of your own nature when you become a Buddha. Intrinsic within your Buddha nature is the capacity to liberate sentient beings in a forceful and active way. This is the aspect of your nature that you will come to rely on when you have completed giving rise to the bodhicitta, and your only hope is to be able to liberate sentient beings from suffering. You will look to that part of you, that element of your nature, that is forceful and dramatic and able to dominate samsara, to suppress samsara through a wrathful display.

Again, we can’t have the superficial view. We don’t understand wrathful display. Maybe a wrathful display to us might be having a temper tantrum. But you must understand that we are talking about the force and power, the enlightened force and power, and potential necessary to liberate beings, particularly during this age, which is the age of kaliyuga, the age of decay and degeneration. At this time, the wrathful beings are even more powerful, even more forceful, because their display is more in line with this time. It is more necessary. This being the time of degeneration, wrathful force is needed. And so in the bardo we should not only not be afraid of the wrathful deities, but we should look to them, look for them, expect them, and rely on them with confidence, because they may be the ones who are able to break through our own ignorance. This is the aspect of our own nature. Again, it is not external, but we have to talk in that way. We say we look to them to be able to break through our ignorance. In fact, we are relying on that aspect of our own Buddha nature to stamp out the hatred, greed and ignorance in our own minds, and the degree to which the hatred, greed and ignorance are ripening. These things are what we rely on the wrathful deities for, and so they are precious to us. And even though many of us like the pictures of the peaceful deities, we like to practice the peaceful deities, we just think they’re ‘friendlier’; we just like them better (prettier, better outfits, friendlier), it is, in fact, the wrathful deities upon which we should rely ultimately. We will need them at some point. There is not one of us that will not rely on that very power, that very display at some point in our spiritual development, to crush the ego, to pierce the veil of delusion, to whip apart the thick covering of grasping and desire that covers us and keeps our eyes closed to our inner awareness, to the awareness of our nature. Guaranteed, there is some point in your development, whether it is during the course of your life where you will have to practice some wrathful deity in order to remove obstacles, or whether in the course of your going through the bardo, it is that very force, that very energy on which you will rely to move you into enlightenment.

That very energy can also be seen sometimes in the guise of our teachers. Sometimes our teachers, in order to break through limitations that happen within our mind, will be very firm with us, very stern with us, very very forceful. I’ve had that happen to me. WhenHis Holiness Penor Rinpoche came here to give the Rinchen Terdzod, he saw an obstacle to my life. There are many reasons for that, and one of them is that I am teaching Dharma from my own habit of practicing Dharma life after life. I have had very little academic training in this lifetime, and so there are obstacles that come with that. These obstacles must be purified, and they are purified through continuing to gather the merit of teaching students as I am doing, and to fulfilling the instructions of my teachers, which is to continue teaching as I am doing. And in that way the obstacles are overcome.

In another way, I rely on my spiritual mentor, just as you rely on your spiritual mentor, and he relies on his spiritual mentor. That is how we look to our own innate nature. That is how we do it when we are physical: We look to our spiritual mentor. So he came and gave a wrathful display. He was extremely wrathful, and it would seem, from the ordinary samsaric point of view, unjustly so. My lama actually accused me of something that both he and I knew I would never do, and he knew that I did not do it, and I did not do it. And other people came and said, “But Rinpoche, she would never do that. She never did that,” There was no proof that it was done. There was no one who told him it had been done; he just picked it up somewhere. Manufactured it. Just pulled it out. So he threw this at me, and all I could do, as a good student, was to just take it, and try to understand how I could improve myself. There was no way to defend myself, because there was nothing to defend myself against. So when his wrathful display was finished, I, of course, was shaken and changed and crying and needing my spiritual mentor—his love and his guidance and his help. At that point he saw that he was finished and that the job was done, and he reached over and he touched my face, and he said, “Now, Ahkön Lhamo, that’s over with. Now don’t get mad.” And I was like, “Mad?” I was just trying to survive this moment. “We’re not mad, we’re trying to live through this!” So I didn’t get mad. And he said that because I didn’t get mad or have any judgment or anything like that, and because I understood what he was trying to do, then those obstacles to my life could be erased. And I remember that after he did that I felt ten or twenty years younger. I felt wonderful, really good, after I understood what had happened.

That is the kind of activity that we may even see on a physical level. That is the wrathful activity of a Buddha. It is necessary to be seen in that way because the obstacles that it is meant to crush are also violent and dramatic and forceful. The force of our own karma is violent, dramatic, and forceful. And so in order to be skillful we have to use that which is equal in strength and superior in strength to all the forces of samsara. That is the nature of that kind of wrath. Therefore you should not be afraid.

Train yourself, then, to recognize the images of the wrathful deities, to recognize their nobility, their purpose, their generosity, their kindness, the love that emanates from them, in order to remain ever ready, as they do, to suppress the obstacles that sentient beings face.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Impact of Karma on the Experience of the Bardo

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

Now listen to how this lama [Bokar Rinpoche] explains this—I think this is excellent. “Likewise the experience of death will be different for each one of you, although there are certain fundamental rules. Consider a house of rooms in which each wall is covered with mirrors. The man living in this house is dirty, has untidy hair, wears ragged clothing, and is always making faces. He goes from room to room, and the mirrors steadily reflect the faded image of an unkempt man with a grimacing face, untidy hair and ragged clothing. Similarly, when our mind is distorted by a lot of negative karma, each of the six bardos reflects suffering, just like the mirrored rooms in that house.” And they have a footnote here about negative karma. “Negative karma: All negative deeds, ones that deliberately make other people suffer, leave an imprint in our mind and will condition our experience and our vision of the world. And that is our suffering, that is what our suffering is.” That is the content of our suffering, that is our only suffering. That is the only suffering we will experience, but it is enough.

“The house occupant could also be clean, well-dressed and smiling. Everywhere he goes, from room to room, he sees a clear and smiling face. The house remains the same, you see, but there is no more ugliness nor appalling sights. Everything you see is pleasant and peaceful. When our mind is free of negative karma and the passions that disturb it, the six bardos reflect a picture that resembles us, full of peace and happiness. Whether pleasant or not, experiences do not depend on the six rooms. An individual fills the rooms with his or her own nature. Likewise, negative experience of the six bardos does not depend on the bardos, but they do depend on our own mind.”

Now, boys and girls, this is a very important point. It’s important because you are living the result of that right now. You are passing right now through the bardo of living. The experience that you have depends on and is resulting from the habitual tendency within your mind, the karma of your own mind, the causality that you have already brought into play. The experience of your present day life is due to that. All the suffering that you will ever experience during the course of your life, , including the cause of your death, and all of the happiness, is due to the habitual tendency of your mind and the karmic patterns of your mind. Literally, think about it this way. If your experience was that of the kind of person who is only here to see what they can get, and upon meeting other people only sees a potential source of satisfaction… And how many of us in samsara are like that? Here is a potential source of satisfaction, and we wheedle and we whine, and we feel sorry for ourselves, and ‘please love me and do this for me.’ Or we do the opposite, which is manipulative: We try to manipulate people into a position where they have nothing else to do but benefit us. And we’re real good at it. In fact, so good we hardly see it ourselves, but that’s what we do.

And then we have another kind of situation where we spend all of our life trying to dominate the people in our environment, and our environment—trying to force it to be what we want so that we can have what we want. The experience of the life passage or the bardo of living for persons like that will be very different from the experience of the person who goes through life saying, “How can I help? How can I contribute more love to the world?” The kind of person that goes through life knowing that it matters much less how much love they get than it matters how much love they give will have a very different experience from the other kind of person. And that’s what this lama is talking about there. Not only during life, but also during death. Our death depends on the habit of our lives. If we are neurotic and frightened and whiney and complaining and weepy and emotional during the course of our lives, think What will your death be like? What has your life been like? Think. This isn’t a great mystery. Everybody has this fantasy of climbing the Himalayas to get to the dirty guy on a rug at the top who knows everything, and he’s going to tell you the secret of life. This is the secret of life. Think. You know, think about this. If this is your passage through life, what will your passage through death be? You’ve got to fix it now.

On the other hand, if you are the other kind of person, if you have been a contributor, if you have been strong, if you have been loving, if you’ve tried to do your best, if you’ve tried to contribute love to the world, if you have tried to practice, if you have tried to calm your mind, if you have tried to make your mind an attractive and virtuous vessel, your death experience is going to be quite different. Absolutely different.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Amitabha Buddha and the Bardo

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

Lord Buddha Amitabha is considered to be that one who once looked upon the suffering of sentient beings as he was becoming Buddha, as he was moving into his fully enlightened state, and saw the condition of sentient beings and began to cry. He grieved in a terrible way. It was a kind of grieving that one can only understand if one has tasted the food of enlightenment. If one has tasted enlightenment and then looked at the condition and suffering of sentient beings and truly seen the difference. There is no other grief like that. One cannot understand that kind of grief. It is unlike losing a loved one or even losing one’s own life. The grief that one will feel, having tasted the natural bliss, the natural birthright that is your true nature, and then watching that while that is so, it is also so that sentient beings are suffering horribly; watching that they are suffering uselessly and senselessly, and that because of their own ignorance they are making themselves suffer, and making their own mistakes, and that all that they would have to do is stop… There is no grief that is stronger or more complete than that: to know, from the vantage point of bliss, what sentient beings suffer. And so Lord Buddha Amitabha gave rise to the most profound bodhicitta, the most profound kind of compassion, a compassion that colored him, that dictated his method, a compassion that filled his intention, that became his intention. And the compassion was so strong and dominating that he made the most profound wishes. And he made those wishes, not as we would make wishes when we circumambulate the stupa, even when we make wishes with faith, but he made those wishes from the potency of his enlightened accomplishment. He had fully accomplished the view of non-distinction. He had fully accomplished the primordial wisdom view of equanimity. He had fully accomplished the ability to see the nature that is the nature of all sentient beings. He had fully accomplished the ability to see the lack of separation between oneself and others.

So when Amitabha looked to the plight of samsaric beings he began to cry, and it was his very tears, they say, that became the emanation which is Chenrezig, the Buddha that gave us the mantra ‘Om Mani Padme Hung,’ that keeps us from falling into the lower realms. That is how strong and how forceful his grief for sentient beings actually was. And so Lord Buddha Amitabha actually practiced in such a way as to set up a pureland called Dewachen, which is the easiest of all the pure lands to enter. It is meant to be a home, a welcoming place, a source of refuge for those of us who have met with samsara and have been so damaged and hurt and traumatized and deluded, and have continued so much in our own habitual tendency without any understanding of what samsara actually is, that we have become almost drunk beyond repair. Even though we too are that nature which is indistinguishable, that nature that is both the enlightened nature and the samsaric nature—while we too have that Buddha seed, yet we are so deluded and so wrapped up in the delusion, that while it is potentially so, you can also say it is almost impossible to expect or to hope that any of us might attain the other Buddha fields.

The other Buddha fields are associated with the kind of accomplishment that sentient beings are very rarely able to have. Lord Buddha Amitabha saw that, and he wept and grieved for those students who would be prevented, due to their circumstances. He was angry and would not accept that some sentient beings would be excluded because of their inability to practice. And he became extremely angry and extremely upset that some sentient beings would be excluded because of their ignorance and their slothfulness. He became extremely angry and extremely upset that some sentient beings would be excluded because they had not understood devotion. He became so upset with these things that he practiced in such a way that the very nature of his pureland is easy to enter. There is an ease of passage. And he made it his work from this point until all sentient beings are finished. This is his work from now until all of us are finished. Think of that. That he would be available constantly—and he doesn’t have office hours either, this is the great thing—he would be available constantly. I have office hours; Lord Buddha Amitabha does not have office hours. No, just kidding! Lord Buddha Amitabha has said that he will always be available for those beings that cry out for him. And literally, if, in the bardo, if you can remember to cry out for him once, and to call his name and to ask him to come and rescue you, surely he will come. He will not be able to ignore your voice. He will not be able to keep away from you. He will come.

The way he has set up his pureland, it will be very easy for you to follow only on that small cry. He’s like a mother. He’s so tuned to the cry of the babies that only the slightest whimper—only the slightest whimper, that’s no effort on your part—will invoke his great compassion. Therefore you can have confidence and faith and trust in Amitabha. He is as sensitive as your own mother was when she heard you breathing and whimpering in your crib when you were unable to fend for yourself. He’s like that. And furthermore, Lord Buddha Amitabha has also given us this practice and he has made his very body, his very nature, accepting of us to the degree that he is instrumental in the transference of our consciousness. So, while his body is subtle, while his body is pure, still somehow he connects with us in a mystical way that we cannot understand, and uses his very appearance, his very nature, as a vehicle to carry us into bliss. It is because he is so frightfully sad for the suffering of sentient beings, who have no hope and have no method, and have such strong habitual tendency that is weighing them down. He is the kindest, the purest. There is no other Buddha like him; he is completely unsurpassed. There is nothing and no one that can meet the kindness and the quality of Lord Buddha Amitabha. He should be considered your singular protector. You should think that his face is always turned toward you, and that all you have to do, like a little baby, is to follow the voice of your mother. A little baby learns very early on where the milk comes from and learns to follow the voice of its mother. And so in this way you should understand that the nectar of Lord Buddha Amitabha is all-pervasive, and it’s easily digested, even for those of us who have no will to take care of ourselves, or to befriend ourselves in a firm and disciplined way. Lord Buddha Amitabha is such that he will not only offer you the nectar and the milk of loving kindness, but he would also take it into his own mouth and digest it within his own body, and give it to you in that way, already digested. That is the kindness and the nature of Lord Buddha Amitabha. You can have complete faith and trust in him. He does not prefer Tibetans; he does not prefer any one kind. He has developed his practice to the point where he has eyes and ears and helping hands that extend in every direction. Right now he hears your voice; there is no sentient being that is separate from his hearing. Even if the tiniest bird were capable of calling out his name, even if the tiniest of creatures, the meanest of worms, has any connection with Lord Buddha Amitabha, he will try in some way to resonate with that creature so that they will have a chance. He is extremely active, extremely persistent in benefitting sentient beings. And when it comes to those of us who have practiced very little and are not very confident, he is our sole guide and mentor and hope when it comes to the time for our own death. So when we see ourselves moving our consciousness into Amitabha, we shouldn’t think that we are moving ourselves into something that is strange or separate or unfamiliar or unpleasant. We should think that we are going home. We should think that we are going to our own kind mother. We should think that we are going to our own truest heart. We should think that we are bathing in our own true nature. There is nothing foreign or unfamiliar, or strange or unfriendly about Lord Buddha Amitabha. He is your greatest hope. And if you remember no other image in your life, if you can never call out to your teacher, if you cannot do anything, if you are utterly and completely helpless when it comes to your practice, then please at least remember the kindness of Amitabha, because he will remember you. You should think like that.

Lord Buddha Amitabha has developed his practice so that he himself is the doorway to liberation. It is through him that we can pass, because he has made himself available. Coincidentally, it is also true that the practice of the wisdom of equanimity is often one of the first accomplishments that we can practice through meditation. Interestingly, when we sit in practice, simple meditation like shamatha, we can think that in that meditation it is possible to practice the wisdom of equanimity. We can begin even in a simple, quiet meditation like that, or just watching the breath, or simply letting the attention rest lightly on space, which is a very simple and very wonderful meditation that all of us should practice in order to help our minds not be so heavy and fixated on samsara the way they are. Keeping the attention just lightly resting on space, one then begins to awaken immediately to the wisdom of equanimity in a small and subtle way. And then gradually through that kind of practice one progresses. So, you see, even then, it is Lord Buddha Amitabha’s wish that that should be the most easy and most accessible method for us. That we should be able to firmly and easily—even those of us who are not excellent practitioners—move toward his nature. Move toward our nature. Move toward Dewachen. And it is through Lord Buddha Amitabha’s practice that he has reached out to us, through making his practice such that it is easy for us.

If you could understand the philosophy of burning the candle on both ends: What is happening on one side is also happening on the other side from our point of view, but in truth there are no two sides. It only appears that way. Someday, some scientist is going to come up with something in quantum physics that will be a mathematical formula that will help some of you to understand that this is how reality actually is. This is what actually is. That it is possible for Lord Buddha Amitabha to practice in such a way as to grease our wheels: to practice in such a way as to create a chute, in a way, that we can just sled down, in a sense. An easy access, a very open method, a very accessible method. That that could be a truth. And it could also be a truth when I say that perhaps in simple meditation one could easily develop the wisdom of equanimity. These are not two separate statements; they are the same statement. When you turn to Lord Buddha Amitabha, ultimately you are turning to your own kind nature. Ultimately you are turning to that to which you will awaken. Ultimately you are turning to that with which you will know again, or awaken to, become cognizant of, the connection. It is that strong connection that I am trying to describe. Coincidentally, that connection will probably be through the Phowa.Then we will know in our heart of hearts that Lord Buddha Amitabha has touched us, just as right now it is Lord Buddha Amitabha who is speaking to you. Because if it were not possible, if it were not so, the truth about how to die and how to be reborn would not be available in the world. It is Lord Buddha Amitabha, therefore, who speaks to you now through these teachings and these words, and you should follow without hesitation, with full confidence, and without question. This is only done because Lord Buddha Amitabha grieves that you should wander any longer in samsaric existence. His nature is that of equanimity; his nature is that of compassion. His nature is that of ultimate depth that we cannot fathom, the depth that is the true empty nature that is our nature. And it is Lord Buddha Amitabha upon whom we can rely as a bridge, a bridge that is easily crossed between ignorance and bliss.

That’s all that we have time for today. I promise you that towards the end of the retreat we will have more teaching, and will have more questions. I know that you have lots and lots of questions. Lots and lots of questions. But I’m hoping that some of your questions will be answered by end of the retreat. Also, I would like you to practice waiting on the kindness of your teacher. Waiting on the kindness of your teacher—that is a hard one. Students don’t want to do that. They don’t want to wait on the kindness of their teacher. They want to ask questions now because ‘we want to know, and we are important.’ You’re not practicing being important; you’ve already practiced that. You’re so darn important we don’t know what to do with you. You are so important we just don’t know what to do with you. You are already important; that has been accomplished. You have accomplished the mantra of importance; you’ve accomplished the mantra of ‘gimme, gimme, gimme.’ You have accomplished the mantra of ‘I think, I want,’ and now you are going to accomplish the mantra of devotion. So what you need to practice now is waiting on the kindness of your teacher, trusting in the kindness of your teacher. Looking for what is already there, rather than defining what you don’t know. I ask you questions, because in the bardo there will be no one to ask questions. You will have done it, or not, you see. That is what we are training for now, so it is appropriate for us to train in that way. Require of yourself to mature. Grow up. Pull yourself together. That’s the kind of thing we have to do in the bardo. Rely on that stability of mind. That’s what we’re training for now.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Practice

The following is an excerpt from a teaching offered by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

I want to remind you. For many people, when they come to a retreat, the teaching section, to them, is the most important section. I can see why: Because you have to have commentary teaching; you have to have instruction. It is that instruction which prepares the mind and ripens the mind. And you have to be in the presence of your root guru in order for the mind to ripen. It simply will not ripen without that. So this is necessary. Plus, teaching is more entertaining. You know, we’re listening, and it’s interesting. So we think the teaching is the superior part of the retreat. Some of us may think, “Well, I’ll come to the teaching but I won’t come to the practice.” Don’t do that. Because while receiving this teaching is the first step and it will help you to recognize that you at least are in a bardo, and you may remember some of the things that I’m teaching you now while you’re in the bardo, the likelihood that you’re going to even remember what I’m saying now ten years from now is not so good. What has to be accomplished in Phowa practice is the practice. When you die, you won’t be doing this practice. You’ll be dying. You will be Phowa-ing for sure, but you won’t be practicing this practice. You will be dying. Get that.

The reason why you want to practice this practice now is because it’s the only chance you’ll have. You need to practice this practice until we receive the desired result: You become familiar with the images; you become entrusting of the images. You create the virtue and karmic connection within this; you gather the virtue and create the karmic connection with Amitabha; you create the karmic connection with this state. But most of all, you need to do the practice because the practice is going to purify your inner channels.

Now, once again, none of you are perfect visualizers, so you’re given a general visualization. That’s all Westerners are ever given. Did you know that? That’s all we are ever given, because there are extensive visualizations for every practice. Every practice has an extensive visualization, an intermediate visualization, and a condensed visualization. The extensive visualization is for people in retreat that have extraordinary capabilities for practice. We don’t even have that capability. There are many people that don’t even consider that they can visualize at all. So we are given a very condensed, abbreviated visualization, and even that you’re not going to be able to visualize clearly. Naljorma, the inner channel, Lord Buddha Amitabha, the little disc, all of that together is a big load to visualize, particularly for those of us who have not locked ourselves into a cave anytime in the last decade in order to visualize. But that’s not the point. Again, trust in your spiritual mentor.

If it were left up to the attributes of the sentient beings to accomplish Dharma, there would be no accomplishment of Dharma, because the Catch 22 is that as sentient beings we don’t have those qualities. It is only through the implementation of the path that we begin to awaken to our nature, that we are in touch with those sorts of qualities. So we’re not depending on your good qualities. You are depending on the good qualities of your teachers. And then eventually others will depend on your good qualities. That’s how it goes.

So, you can do the visualization as simply and as profoundly as you are capable of doing. Relax your mind. Do not allow your mind to become tense if you forget one aspect of the visualization. The tension is more detrimental to your practice than the absence of visualization. So rather than becoming tense, do not make a big deal. Don’t be such heavy breathers. Lighten up. Just relax. Do what you can. If all you can visualize is the tube, the jump, and the intention, and maybe even just knowing that Lord Buddha Amitabha, because of what I have said, is the kindest and most motherly, in a sense, of all the Buddhas—that confidence. You know, we pride ourselves on being so sophisticated: We’ve gone to school; we can think anything through; we are so proud of our Piled Higher ‘n Deeper little pieces of paper and all that stuff. We’re just so proud of that. And yet, here, in this case, if you can’t visualize, and you don’t have a brain of a goose, which I’m not sure any of us do, if you don’t have any kind of brains whatsoever, I mean, nothin’, (I get New York-y when I do this, I’m sorry, it sneaks up on me!), but common sense is common sense. Let’s think about this. If you don’t have the brains of a flea, and all you have is the simple trust that an infant would have when they cry and they have learned and they know that their mother will answer, that is superior to the kind of mind that’s going, “Let’s see now. What color was Wuma, and what color Amitabha? Oh, he’s red. Now what shade of red?” We have to know these things. And let’s see, “How is he facing, and where was his leg?” And that sort of thing. And that heavy energy that you’re using to fixate yourself in the mud of your own ego clinging is not very useful. So, drop it. Better to have the simple image, simple intention, and innocent visualization of a child who knows its mother will answer their cry. That will get you into Dewachen a heck of a lot faster than trying to be correct. Okay?

So remember that your spiritual guides, the teachers that give you these practices, do not expect you to be Buddhas now. It is not to be hoped for that you will do this practice excellently, but it is to be hoped for that you will do it with confidence and faith. Even if you cannot visualize at all, the simple intention is helpful. So you try to do the best that you can, and the more you visualize the more you learn. The easiest are the singular visualizations like this, where you have one character, then on top there’s another character, but basically you just have, in one line, two main characters. There are many practices where you have so many Buddhas and Bodhisattvas that you have to visualize so many different things. This is meant to be very simple. At the time of your death you may not even have the where-with-all to visualize anything, because, remember, as the elements begin to dissolve, those qualities which go to make up the kind of consciousness that can visualize will also be dissolving, and at that time you will have only your former training. When you actually do practice your final Phowa, when it is time to die, you will be relying on the training that you’re doing now. So this training you should do with faith, simplicity, strength of purpose, conviction, pure intention to benefit beings. Those are the things that matter. And the simple doing of the practice, the simple moving of the winds through the central channel, with the intention of devotion toward Amitabha, and understanding, this is the result that cleans out the central channel. And that’s what you want. Because when you get ready to die, you will need that central channel cleaned out.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Ph’owa: Precious Opportunity at Moment of Death

An excerpt from a teaching called Awakening from Non-Recognition by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

I would like to talk about a practice that we do in order to prepare for the time of death. This practice is called P’howa. In P’howa, we practice clearing the central channel, opening up the psychic apertures that block us, coming into a state of awareness of what the death experience is. In P’howa we practice ejecting or sending the consciousness through the central channel so that at the time of death we can die consciously—that is to say, not simply have the experience of death overtake us the way life has overtaken us, but rather die intelligently, participating in the transference of consciousness from ignorance to bliss.

In the practice of P’howa we are taught that at the time of death when the outer breath ceases, there is a period of time between that and when the inner or more subtle breath ceases. That time varies according to the conditions surrounding the death, the condition of the person’s mind stream, the karma of the person and his or her habitual tendencies. There are many different factors. But when death actually occurs and all of the breath ceases, both the outer breath that is very visible and measurable and the inner subtle psychic wind, at that moment there are three very important events that happen. It’s critical that as Buddhists we understand this, think about this intelligently, prepare for it and make choices.

The first event is the disengagement of the white Bodhicitta or male spiritual essence that we inherit from our fathers. We perceive this to be seminal substance but it is actually the white Bodhicitta in its mystical form. That white Bodhicitta disengages and drops from the top of the head to the heart area of the central channel. When that happens, there is a corresponding vision as we enter into the bardo state called the white vision. That white vision has two aspects and there are two results. We prepare for that in P’howa.

The second event that happens is the disengagement of the red Bodhicitta or female spiritual essence, which is the mother’s contribution. At the time of death that red Bodhicitta disengages and rises up the central channel to the heart. At that time we have the corresponding vision, which is called the red vision. That red vision has two aspects and two results. Again, you will learn about that when we study P’howa.

The event that I want to discuss is the third event, which occurs when these two substances, this red and white Bodhicitta, meet in the central channel. When that happens, there is the clear or black vision. That particular vision is extremely important because, while everything in the bardo depends upon our capability to move from a state of non-recognition into a state of recognition, the most glorious opportune time for this movement into recognition is when the worldly life-bearing constituents dissolve and we are in that state that I’m describing. Every method that we practice in Vajrayana is geared toward providing that kind of recognition both in the waking state and at the time when the red and white Bodhicitta meet.

That state is a very fortuitous state. To the excellent practitioner who understands the point of the path and who has practiced and achieved some accomplishment, that moment is a tremendous opportunity. The excellent practitioner will look forward to that moment more than to any other event in his or her life because that moment holds the strongest potential for recognition. A mediocre practitioner will say, “Well, you know, it sounds good to me, but I don’t know, I’d rather vacation in the Bahamas!” or something like that. The mediocre practitioner will have some fear about it, which will be more or less according to their level of competency, and will question whether or not that state of recognition could possibly occur at that moment. For the non-practitioner, that state is a complete unknown.

Now, why does this moment hold such a tremendous opportunity for the practitioner, and why is it a completely different experience for the non-practitioner? Non-practitioners are basically in the same position in that state as they were in their lives when they lived in an ongoing, confused and deluded state of non-recognition, thinking that I am this thing that is contained right here in this box of flesh and you are out there totally separate from me, and there is no connection. That state of non-recognition is the mind of duality. It is the mind that separates self from other. It is the mind that experiences acceptance or rejection, hope or fear, and hope and fear mixed up at the same time. There are many different ways to determine what our consciousness is like in the state of non-recognition. Simply look at what your mind is doing right now.

If we were awake as the Buddha is awake, we would understand that duality is not even logical. Coming from the perspective of enlightenment, of realization, of awakening, we would understand that is not realistic at all. It cannot be. So this state of non-recognition is the state in which we seemingly remain in a certain solid condition where everything other than our perception of self-nature seems to be projected outward and seems to be happening to us. We think life happens to us. We seem to be both victim and oppressor, and we seem to experience both the result and the condition of both. According to where we are at that particular moment in our lives, we will think ourselves to be either the victim or the oppressor.

Now, according to the Buddha’s teaching, nothing is happening other than the primordial wisdom nature that is the ground-of-being along with its display, which is very much like the relationship between the sun and its rays. The dance, the movement, the display of the primordial wisdom nature is as much a part of that nature as the sun’s rays are a part of the sun. Yet we experience things in an extremely deluded way. Everything seems to be separated, categorized, dualistic, and so we are lost in a state of non-recognition, not able to understand who or what we are or how things actually occur.

In P’howa, when the red and white Bodhicitta come together, the subtle material constituents, which bind us to our experience into this physical reality, into a time and space grid or a sense of continuum, naturally dissipate. When the body is ceasing its activity, that which we have called “I,” which seems to have existed since time out of mind, we do not perceive to disappear into nothing. We perceive that sense of “I” continues and remains, mostly due to ego-clinging and desire, through the idea of self-nature as being inherently real. However, at the time of death, again when this red and white Bodhicitta come together, there is this brief period of time when all of these constituents dissolve. This is almost like the space or pause between an inhalation and exhalation. Unfortunately, our language is a deluded way to communicate this information because it is not made to convey enlightenment. It’s made to convey only delusion. Please forgive me for that. So there is a moment when the constituents dissolve, when there is this pause where nothing new arises. Even though we are still lost in the state of believing in self-nature as being inherently real, some sort of subtle reassembly has not occurred just yet. The constituents have simply dissolved and there is a moment of pause.

Once the constituents disengage, most people (99.9% of sentient beings) who have not had the opportunity, or for whatever reason did not practice to some level of accomplishment, will not be able to recognize that the components that cause us to engage in the automatic projection of our karma and mind streams into external experience have momentarily ceased. To the ordinary practitioner at that time, consciousness simply faints or goes into what is very much like a sleeping state. That is the experience of dying. It seems as though something ends. There is no recognition of the primordial ground of being that is our nature and that is momentarily revealed at that time, revealed just as clearly as it can ever be.

Now here again listen to the language of delusion, “clear as it can ever be.” If we could conceptualize that nature as an “it,” we’d probably be able to see it at that time. But the constituents have dissolved, and we are simply seeing the naked reality, the naked face of the ground-of-being that is our nature. As non-accomplishers, as those who are still not awake, we do not recognize that moment. It appears to us that it is simply over. It is ended. We have had a certain white vision and there is a feeling of moving through a tunnel and all that stuff they write about in books. A lot of it is correct, but they don’t tell you about the part that happens after that, which is the red vision, and then the experience of dying. As we arise from the state of unconsciousness, our habitual tendency to conceive of self-nature as being inherently reasserts itself. When we’re talking of a habitual tendency, we’re not talking about 75 or 80 years, we’re talking about time-out-of-mind, inconceivable time, time that you cannot name, count or measure. So naturally a habitual tendency simply asserts itself. Then we continue to go through the bardo, again projecting consciousness outward, but it’s a very different experience without the rules and regulations associated with physical life.

What happens to accomplished Bodhisattvas or perhaps even to very good practitioners at that precious moment when all of the constituents dissolve? They recognize the clear, uncontrived, natural, conditionless face that is our nature, that state which is literally free of any and all conditions and therefore cannot be described, which is fundamentally complete and yet without beginning or end. That state is free of discrimination, free of any kind of determining factor, free of time and space as we know it, free of anything that we can name as distinction or condition.

At that moment that state is revealed, and for the practitioner, it is as precious, so close as to be beyond your breath, beyond your blood, beyond your marrow as you understand as a physical being. That state, then, when the constituents all dissolve, is suddenly tasted, understood, recognized—recognized in the same way that a child will recognize its mother and the mother will recognize its child. “Recognized” is the only word that really works.

Those of you who have been parents, particularly women I think, have this kind of experience more frequently. It’s not to say that men don’t have this experience, but women who have birthed a child have a mind bend to see something that was inside of them and now it’s outside of them and they know it. There’s this thing that happens. It’s there in the same way that a child begins to move toward its first cognition, the first thing to which it reacts. You can see this in newborn infants. They will start to look for the sound of their mother’s voice and even be comforted by being held close to the mother’s chest because they recognize the mother’s heartbeat.

This deep, intimate recognition doesn’t even touch the recognition that happens to the qualified practitioner or Bodhisattva when the constituents dissolve and they are free to see their true face. That nature that is revealed at that moment, simply because nothing else is going on, is more intimate than the experience that I have just described. Again, those of you who have borne children and know what I am talking about can really relate, and others of you can relate in your own deep, inmost experience, perhaps remembering from your own childhood.

The revelation of that arising is so intimate and so profound. It is that revelation that we look to accomplish, that we try to understand, that’s the game plan here. At the time of death when the constituents dissolve, we wish to arise from the darkness not filled with desire and habitual tendency continuing through the bardo and through samsara like a bee in a jar like we always do. Instead, we wish to arise in the state of recognition that is the same as what the Buddha described when he said “I am awake.” This is a state that brings us to awakening. That is what awake is: that recognition.

So for the excellent practitioner the hope is that at that moment we will recognize that which is not separate. What is the thing that we recognize at that time? It’s not a thing. It’s no thing, nothing. It is no thing, and yet it is that which is the ground essence that is our nature, the ground-of-being. Isn’t “the ground-of-being” a provocative phrase? We’re not talking about some external divine reality that we have to go toward. We’re not going toward the lake, you know. That’s not what we’re doing here. It is the recognition of that nature that is the ground-of-being, that ground-of-being that is our nature. In that state, indistinguishable, one cannot determine the appearance of phenomena or the appearance of self-nature, or the difference between. One cannot see differences. That recognition is of our true state, our true nature, which is that which is free of such distinction.

© Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

The Opportunity to Practice Phowa

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

The signs that you must see in order to know that you are prepared for death have to happen now. They don’t happen before you die; they will not happen before you die. You will not have time at the moment of death to prepare for your death. That isn’t going to happen. So the signs that have to happen now must be received at this time. We want them now. This book, this preparation, this Ngöndro, which helps us to gather merit and helps us to purify karma, and helps us to make it possible for our minds to have the kind of quality to be able to hold, like a good bowl without a crack, such a practice, this is for now. Now is when you have to do this. The winds have to be purified now. The channels have to be unkinked now. Your mind has to be stabilized now. You have to learn not to be such whiners now. You have to learn to renounce cyclic existence now. You won’t have time at the time of death. You’ll have time for maybe a quick thought. If you’ve already practiced renouncing cyclic existence, at the moment of death you will have time to simply give all of that to the Three Precious Jewels. That you will have time for. That kind of inclination, that kind of giving, you will still, even after the elements dissolve, have the wherewithall to practice. But of course you will not have time to practice every aspect of the visualization and the prayers.

Forgive my language, but I have to scold you a little bit. Do you think that the Dharma was written by enlightened beings that were so anal, excuse me, that they said, “Well, if you do every one of these prayers, especially the ones that I’ve written, then we’ll let you in! But if not,…” What are you thinking! You know it’s not like that. It can’t be like that. That would not be logical or realistic or sensible. What superficial view of reality do we have if we hold such bizarre and crazy ideas? What we are doing now is to prepare ourselves—through gathering merit, through accumulating virtue; through purifying our inner winds, channels and fluids; through understanding what bardo is, through studying and contemplating the nature of cyclic existence including the bardo, through having preparation as to how the bardo experience will actually take place; through developing devotion. All of these things have to happen now. If you’re waiting ’til, oh, a week before you drop dead, what is that? First of all, you don’t know when that will be, and second of all, what’s a week? Even if you have that much time, you don’t have enough time during the course of a week, or month, or even a year. Preparation starts now, and you do what you can as quickly as you can with as much devotion as you have now. With as much devotion as you can now. So that’s what has to happen.

At the time of one’s death, if you are fortunate enough to have spent a long time dying, and you have been in the bardo of the condition of your death, which means that the cause of your death is already within your body and is active in your body, so you’ve known for a long time that you’re going to die… And let’s say you have the good fortune that a physician—this would have to be a heck of a physician, wouldn’t it—would come into your room and say, “Well, looks like four o’clock today. That’s what I say. Four o’clock you’re on your way out. Toes up kid, four o’clock.” And let’s say everything is perfect, and somewhere around two thirty you still have your mental faculties complete so you pick up your book and think, “I’m just going to open my practice.” This could happen. I mean, it could happen; but really, what is the likelihood? There’s no likelihood that that’s going to happen. The rarity of such a situation is ridiculous. Plus the fact that when people are getting ready to die they’re not at their best condition, you know. They’re not necessarily right with the program. There are some people that remain alert right until they cross that threshold. Lucky them, but it is not [usually] the case. So don’t you think that, since this Phowa was authored and given to us by those who have achieved enlightenment, who have practiced Phowa successfully, that they would have taken into consideration that this Phowa is written for you, for sentient beings? It is written for sentient beings that have not solved their problems yet, haven’t got renunciation down, haven’t got anything down yet. In fact, this kind of Phowa is kind of Last Hopeville. It’s really designed for those who could not practice generation and completion stage practices excellently. Those kinds of practitioners who can practice those practices excellently probably will not [need] the Phowa. So you must understand that this is not only possible, it is not only accomplishable, do-able, but is also necessary; and it is necessary for you to step back and have a proper view about it. Lighten up. Give yourself a break. Give me a break. It will come to you; We’ll get it done, don’t worry.

So, now that I’ve finished spanking you I’ll teach you some more. That’s not a bad spank, is it? Nah.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

The Necessity of Training in Phowa

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

Last time I saw you guys you were dead; and the Buddhas appeared to you, and you were still dead. We spoke last about the section of the bardo where the Buddhas and the Bodhisattvas appear, and we spoke of the forty-two peaceful deities and the fifty-eight wrathful deities. I explained yesterday that on the appearance of the peaceful deities, one should understand, first of all, that one is unfamiliar with that. Remember, to understand in terms of Vajrayana why we act the way we do and how we should practice, we have to understand what an important part habitual tendency takes. Remember, when the Buddhas appear to us, the peaceful Buddhas that is, in the bardo state, they appear to us with extraordinarily brilliant lights. I have explained to you that in that state of the bardo those lights may even be so impactful that they will also impact the other senses—like a light so bright that you can almost hear it, if you can imagine such a thing. I actually had an experience like that. I once had a pulse of light flash to me from one of those newfangled flashlights that have big halogen bulbs in them. You’re not supposed to look at them. If you look at them, they will damage your eyes. You can’t look at them. I had a pulse of that sent at me and it actually registered in my ears. I don’t know whether, scientifically, it meant there was like a pulse of blood in my ears, as a strong reaction, or whatever. But your senses do shift like that, particularly in the bardo. There are no clean cut lines for your senses in the way there are now. Clearly, smell goes through your nose now; clearly hearing goes through your ears now. Well, of course, in the bardo, although you have those same habitual tendencies, you do not have the same definite places for this information to come into, and so there is something of a bleed through.

When the Buddhas come to you, again, that will be very unfamiliar if you have not practiced. The brilliance of the light of the Buddhas will be unlike anything you’ve ever seen; and it will be somewhat terrifying if there is no preparation. It will be much more comfortable to look at the corresponding other lights that come at the same time. We talked about Buddha Vairochana. He appears on the first day and his light is the blue light, and it will be so brilliant it will almost hurt—so brilliant—because it is not our habitual tendency to have awakened to that element of our mind, of our nature, that is in fact identical to and inseparable from that blue light nature that is Vairochana, you see. We will not have had time to do that so we are not familiar. It will be exactly the same phenomena that causes us not to see the black, or clear, path in the first part of the bardo experience. Unfamiliarity. We will, however, as I said yesterday, be familiar with the other light that shows at the same time, and that is the light of the god realm. In a sense, the light of the god realm, which at that point will be a very soft, welcoming, and very sweet kind of white, will be much more familiar because we will have exhibited some of the qualities that it takes to get into the god realm—that is, some accumulation of merit—and we will also have accumulated some of the unfortunate problems, or the obstacles, that cause us to be born into the god realm. So we have much more familiarity with them than we do with our own primordial wisdom nature. Interestingly, as the different Buddhas appear, and then as the different realms appear, you’re also looking in a sense at the flip side of the same cointwo different sides of the same coin. One is our pure nature, and the other is a display of our nature in defilement, in confusion. Of course, we will have the strong habitual tendency to go toward our nature in defilement, stronger than we will to go toward the purity of our own buddha nature because, simply, we have more familiarity and more habitual tendency with our samsaric nature than we do with our awakened nature.

So, of course, this is something that you are being prepared for right now. When you hear something like that you think, “Oh, that scares me. Of course I’m going to want to go towards a soft, glowing white light more than I’m going to want to go towards something that’s almost painful it’s so bright. So I want to be really prepared for that. How can I prepare for that?” Those of us that have no spaciousness in our mind and have not practiced very much, and have a tendency or habitual pattern for our minds to act in a very neurotic way will think things like, “Oh, I have to practice liking bright lights, . I have to practice not looking at soft lights and not liking them anymore.” really, that [kind of thinking] is completely unnecessary. Again, have faith in your spiritual mentor. You must know that you are already, right now, applying the antidote for whatever fear you might have had about going into the bardosimply training in the knowledge that there is a bardoand to the degree that when you hear this information, you hear it as a respectful student would hear it, hearing it from someone who has crossed the ocean of suffering, hearing it from the Buddha who has given us this information based on his many experiences of crossing the ocean of suffering himself, and also helping others to cross the ocean of suffering. So as a student our posture would be to listen and go, “Yes, yes, yes. Thank you, yes.” That really would be the perfect posture.

Of course our training tells us, “Well, we have to think things through. We have to be individuals.” But that very thought will prevent you from absorbing these teachings that you have to remember on a very deep level—a memory that is really deeper than the mind that you use to call yourself ‘I’ with. It will have to go much deeper than that. And the only way it’s going to go deeper than that is if the student practices devotion while hearing. Devotion is the bridge; devotion is the method. That is why it is a useful practice that connects the student and the teacher and makes the information, in a sense, go in even more. The student who does not take advantage of their teacher’s teaching simply has no devotion. It doesn’t have anything to do with how good a practitioner they are or how lazy or slothful they are. Of course, those are elements, but really, it has to do with the lack of devotion. The student does not have the karmic scenario to make a bridge by which the lama can reach them and touch them. We assume that the lama you have chosen is qualified. Once you have chosen a lama, you should have chosen them on the basis of their qualifications, on the basis of their ability to speak to you. Once that happens there is no room for any doubt. You should have spent your time considering and thinking and wondering and asking yourself, and looking and checking. But once you have chosen, there is no more time for the head games that you play as a student. Now you have to apply yourself, and that’s the only reasonable thing to do at that point. The time for doubt is finished. The time for practice and preparation has now begun. Now that responsibility becomes yours. The teacher can lead you; the teacher cannot force you. It is up to you to follow. So that is what has to be done.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

The Time to Practice Phowa is Now

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

I would like to explain one question that I think is necessary to clear up at this point, because if it isn’t cleared up, you will assume you know more than your spiritual mentor. You will assume that you know how things will go at the time of your death, and you will not follow through with your practice. Many people look at their books and they think, “Well, here’s a pretty thick book and here’s a kind of thin book. I have no idea whether, at the time of my death, I will have time to open my practice.” Well, you’re right, you don’t have any idea whether at the time of your death you will have time to open your practice. Now do you really think that wasn’t thought of? I mean, c’mon guys, lighten up. Remedial Dharma 101. This has been thought of. Really. Lots of people have died. We pretty much got it down. So worry not. Now here’s what actually has to happen. This book [thick] and this book [thin] are not for the time of your death; they are for now. They must be practiced now. There’s a really good chance that at the time of your death you will not be able to pick the books up in time. And you may drop them. And you may not have enough breath to finish. Really. This has all been thought of. Don’t worry. These books are for now.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved