An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo from The Spiritual Path

We never lose sight of how we feel. We are always monitoring ourselves. We want to feel free of suffering, free of stress. Sentient beings strive endlessly to be happy, so it is very difficult to achieve a sustained, sincere practice of generosity. Think what you have done over the last 24 hours. Work? Practice? Television? Family time? Social obligations? Was your first and foremost thought to benefit sentient beings? Or were you doing things to strengthen your ego in some way, to make you feel better? Mostly the latter, I think. Even our Dharma activity is often done to make us feel better about ourselves—to make us feel busy, wanted, necessary, energetic. Or, perhaps, spiritual, holy, and pure. We always have our selfish purposes, so it is difficult to be generous.

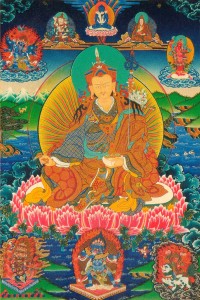

How should one be generous? How should we think about generosity? To begin with, we should not consider phenomena something we can have or not have, something that attracts or repels us. We should view all phenomena as a pure celestial offering that we can actually make to the Three Precious Jewels. We should view our entire world as an exquisite, vast celestial mandala. We should think of phenomena as Mt. Meru, surrounded by its beautiful continents. We should think of all sights, smells, sounds, sensations as precious jewels that we offer to the Three Precious Jewels themselves. It is a more profound version of what we do in our Ngöndro as mandala offering. The deepest way to engage in the practice of generosity is to offer one’s environment continually. But how many of us do that?

Think, for instance, about the way we react to food. We eat food with desire. We taste it with lust, more lust than we think. Shopping for food, we want the best apples, don’t we? The purest, the finest. We want the best carrot cake, the best vegetables. We even lust after color. Our eyes, our feelings are drawn to it. We think we look good or bad in a certain color. We perceive color with attraction or repulsion. All our senses function like that. Actually, generosity should be practiced in such a way that we offer the very senses that we have. But do we offer our taste? Our hearing? Well, we might say that. But we can’t wait for the next sound, the next taste. We cling to our existence as a sentient being, a feeling being. We long for the next touch, the next sight. When you go for a walk, what do you do? You look at the flowers and trees. You sniff the air, smelling everything. The senses are yours. And you have no idea of offering, no intention of offering them to the Three Precious Jewels. And yet, that would be true generosity.

What is the basis of that generosity? How can such an offering be of benefit? You may think: “If the Buddha wanted my taste, my sight, my hearing, my touch, he’d get his own! A truly enlightened being can manifest all kinds of incredible siddhis, or powers. So why do I have to offer this phenomenal existence to the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas?”

Well, why do you have to do that? There’s a real logic behind it. How long are you going to have your senses? You’re going to have sight until your eyes go. Even if your eyes last until the end of your life, they will die when your head dies. You will only have touch as long as you have skin to touch with. Your perceptual experiences will not outlast your body. So what are you holding on to? The traditional teaching says that at the time of death, we cannot take with us so much as a sesame seed. You take only your cause-and-effect relationships and habitual tendencies. So if you have clung to your experiences, establishing your particular neuroses at every moment, that is what you will continue to do in the bardo. If it has been your habit to look for approval and to gather things, situations, people around you for that purpose, you will not be able to take any of that into the bardo. All you will have is the habit of that longing, that desire—and the karma you have engendered from reacting to that need.

How much better to practice generosity—to offer your five senses and all phenomenal existence to the Three Precious Jewels. Why? You create a stream of merit. Offering is one of the major ways to accumulate merit, and that merit can be dedicated to benefit sentient beings. In fact, you can visualize yourself and all sentient beings offering the five senses, offering consciousness itself as we know it. You can think of all sentient beings gathered together with you making offerings of the three thousand myriads of universes purified into a precious jeweled mandala.

What is the value of such an offering? It cuts to the bone. It is so profound that it transforms the entire perceptual process. This deep level of offering pacifies our habit of clinging to cyclic existence. It purifies our self-absorption and selfishness, and we can offer the merit to the countless beings who are themselves constantly involved in selfishness and self-absorption, unaware that they can make any offering at all.

Unfortunately, we are afraid. If we offer something, the Buddha might take us up on it. If I offer the experience of being the mother of my beautiful daughter, maybe they’ll take her away. If I offer all my clothing to the Three Precious Jewels, they might take that away. We fear that something will be lost to us. But you can see that this is a product of our delusion. Our experience of phenomena depends entirely upon karma. As our karma becomes more purified, more virtuous, as our minds become more spacious, more relaxed—our experience can only be better. Suffering only happens due to clinging and desire. In our delusion, we continue to lust after experience, and that lust continues to cause our suffering.

The practice of generosity is an antidote to all that. There is literally nothing to hold on to and no one to do the holding. Everything you have ever experienced—all you will ever experience—is the result of the condition of your mind. Why not then practice this deep level of generosity? Why not view phenomenal existence for what it is? You will in the end, anyway. You’ll see it disappear before your eyes. At the time of your death, you will see the elements disappear, dissolve. Whether or not you will recognize what is happening is another story. (You may merely pass into unawareness, and that would be for one reason only: you lived in unawareness.)

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo