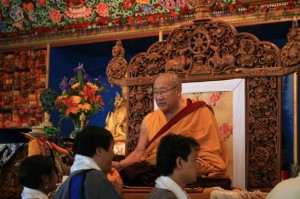

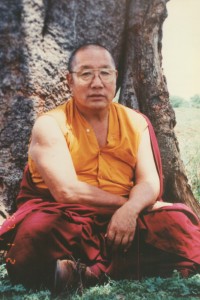

The following is respectfully quoted from “The Dorje Chang Thungma” composed by Benkar Jampal Zangpo a commentary by Chamgon Kentig Tai Situpa

Now going into a little bit more detail, the first is (and this is going with the particular order) zhen log; the literal meaning of which is one thing but it really means turning our minds towards enlightenment instead of samsara–turning our mind from samsara to enlightenment. It means that instead of going in circles, we now decide to go straight; because if we go in circles, no matter how big or how small the circles are, we still end up in the same place. The masters of samsara are going in such big circles that they don’t even know that they are going in circles–they don’t feel [that]; that is what we call ‘success’. But then after many lifetimes they end up in the same place, they don’t get anywhere. But those of us who are not good at samsara, our circle is so small that sometimes we just spin, then we get sick and we know something is wrong right away, but we still do it again and again and again. So that is both of us in samsara, going in circles.

Now the real meaning of zhen log is, instead of having attachment to samsara we turn our mind away from it by knowing that there is no point. For example, each one of us has been the king and queen of the universe countless times in the past; also each one of us has been born as a worldly god countless times in the past; each one of us has been born in the hells countless times in the past; each one of us has been born as an animal countless times in the past, and in the same way as a human being–right now we are human beings, right here. And each time we have done similar things to what we are doing right now–we want something, we don’t want something, we try to achieve something, we are very happy about achieving it. It is like trying to hit a target with a stone. For example, get the smallest thing you can and put it way over where it is almost impossible to hit, then find something very small and try to hit it. When you hit it you’re happy and when you can’t hit it you’re very upset; that is how samsara is–we make our own conditions for happiness; ‘If I get this I am going to be happy and if not I am going to be upset.’ You can get so many things, but you don’t even see them because you are not getting what you want. You might get so many things on the way but you want to get rid of something, and you will not be happy until you get rid of it, but on the way you are getting rid of so many things you don’t even see that, because you are focused on getting rid of one particular thing. So achieving something, avoiding something, all of these things are the kinds of conditions that we make, that we create.

Just go and look at the people in the street and you will know. For example, some people have their hair one way and they think it’s nice, other people have their hair another way and they think it’s nice, and other people have it backwards and they think it’s nice, then other people make it another way and they think it’s very nice. It is all created by us, all of these things, including money, including power, everything, what is precious or not so precious, everything we create and then we follow that. We follow that and make such a big deal about it, we invest so much of our time and energy in these things; that is samsara. It doesn’t mean bad and doesn’t mean good, but I guarantee you, a the end of the day it is exactly the same: whether youy are the Maharaja (Great King) of planet Earth or a guy in the street begging for a coin, in the end it is the same. If you are the Maharaja of the planet Earth you will be crying on your throne, which can be made out of gold inlaid with diamonds the size of your fist, all around, above and below, everywhere, but you will be crying there. The tears that come out of your eyes are the same tears. And if you are a beggar sleeping on the pavement under a tree, being bitten by mosquitos, adorned with cockroaches and all kinds of things everywhere instead of big diamonds, and you are crying, the tears are the same. The suffering is the same, the happiness is the same. At the end of the day it is the same. We often say that when we die it is the same–the beggar goes alone and the king goes alone, the most powerful go alone and the most powerless go alone. But in my opinion you don’t even have to die, right now it is the same. For example, you can eat chapati (bread) and dhal (beans) in a cheap dried leaf bowl or you can eat the rarest dish on a plate of gold, but the purpose of both is to fill your stomach. You are hungry so you eat; after eating bread and dhal you get pait naram (a smooth or full stomach) and after eating from a gold plate you also get pait naram, it is the same thing. Anyway, I am talking about pait naram and all of this in a Mahamudra context–of course Mahamudra is about everything so it has to include that.

This is in the context of turning the mind away from samsara, but this doesn’t mean against samsara, it is for samsara. Because, what would be the best thing for all sentient beings in samsara? To best thing would be to have a Buddha to guide one, and each one of us wishes to be that Buddha. In that way we turn our mind away from samsaric way to the dharmic way and the Mahamudra way.

Zhen Log Gom Gyi Kang Par Sung Pa Zhin,

As is taught detachment is the foot of meditation,

Ze Nor Kun La Chag Zhen Me Pa Dang,

Please grant your blessing,

Tse Dir Doe That Cho Pay Gom Chen La,

To this meditator who is no longer attached to food and wealth, and has cut ties to this life,

Nye Kur Zhen Pa Me Jin Gyi Lob

So that there is no attachment to honor and gain.

That is the first four sentences of the prayer. It means that turning the mind away from samsara is like the feet, legs, it is the foundation; that is number one, the first step. How we do that is by overcoming attachment for anything that is related to samsaric comfort, such as food, material wealth (fortune), fame, all of these things, try to overcome attachment for them, clinging to them. Also there is emphasis, tse dir doe thag cho pay gom chen la–gom means meditation and chen actually means meditator–the meditator should be free of all kinds of ambitions for this life. If I want to be famous, if I want to be rich, if I want to be powerful, then I am not a good meditator. But if I wish to be in peace, if I want to have wisdom, if I want to be able to make others happy, if I wish to be able to become a source of aspiration for others, for their wisdom, their happiness, their joy and their harmony, not struggle, not conflict, that is tse dir do thag cho pay, a person who has decided not to have any interest whatsoever for anything of this life; that is a good meditator. I’m not claiming that I am a good meditator, but anybody who is a good meditator, a good yogi, is a person who is not attached to the so-called nice things of this life and any ambitions for this life; that is a good yogi. Therefore, please bless me so that I will not have attachment for the respect of others and the offerings of others–material offerings and mental respect. I should have no attachment and clinging for that. That is the first four sentences.

This gives a very clear description of why Milarepa ran away from one cave to another–because others were making offerings to him and others were coming to seek his blessings and having a lot of respect for him and all of that. So if he stopped practicing in order to bless them it would be a very good thing, but then he would not have become enlightened. He would just be a quarter of the way to enlightenment, and then he would be using that so he would not go further. Then if he got attached to all of that, then he would have gone backwards and have become less than what he had achieved. It is like charging a battery: you charge a battery and then you use it and the battery goes down, then you have to charge it again. So it becomes like that, therefore nye kur zhen pa me par jin gyi lob.

This is really a very, very serious aspiration prayer of a serious and really dedicated yogi; that we have to understand. It doesn’t mean that all of you right now should have no ambitions for this life, no plans for this life and no attachment for anything. If you can that is wonderful, but whatever project, whatever business, or whatever kind of job you have, it will fall apart. Everything will fall apart, that is for sure, because if you just stop right now, everything you have planned will fall apart. But to get enlightened for the benefit of all sentient beings is worth it. But if you just get excited [about that] and give everything away, then after a couple of months think, “I miss this and I miss that” and try to come back, you will have a very, very hard time because you’ve made a big mess of everything and you have to fix everything. For example, if you abandon everything and then after two years come back and want to claim everything back it will be very difficult, because the minute you abandoned it everybody grabbed it, so when you come back after two years, everything that was yours will belong to someone else. You might have to file twenty court cases, which you may win or lose, but you will not have the money to pay for the lawyers, so it will be a big mess, a practical mess. So if you really want to be a yogi that is one thing, but if you just want to have a try then that is another thing. You can have a try for one week, just make a program so that for one week your attention is not required; you know, your telephone doesn’t have to be answered for that week, your emails don’t have to be answered for that week, so for that week you can be a yogi, a ‘yogi week’. So if you want to have a try you can do that, people do that, they call it a weekend retreat or a holiday retreat, all these sorts of things, but that is not a real retreat. A retreat for a real yogi is until you attain realization. For example, what kind of vow did Milarepa take before he went into retreat? He said, “I will not return to society until I attain enlightenment. If I do, I want all the dharma protectors to punish me.” He said that, that was an ultimate vow that he took. Then he said, “If I die without attaining enlightenment may I die in a cave in the wilderness so that nobody knows I am dead, and nobody will be there to cry for me. An may my body be consumed by little insects and sentient beings so that there will be no trace of me left.” He literally said this in his gur (people call it songs but it is ‘gur’). That is a real yogi’s vow. Without that sort of thing, trying to imagine that we will become a Buddha in this life is not really a possibility. That is my understanding, but of course I can be wrong, but it doesn’t look that way to me–I haven’t seen anywhere in any text about a great being attaining enlightenment without totally renouncing samsara.

But renunciation has many ways–no attachment at all is renunciation. For example, the King of Shambhala, Buddha manifested to him as the three mandalas of the Kalachakra and empowered him on one seat (without getting up from that seat the King was enlightened). That means he was ready for it; renunciation and everything took place right there on his seat. Buddha manifested above as the mandala of the stars, in the middle of the mandala of the deity, and below as the mandala of sound. So sound, the deity and the stars, three mandalas manifested to the King of Shambhala, empowered by the Buddha in the form of the Kalachakra deity (which has about nine hundred manifestations within the mandala itself). Inthat we he was enlightened right there. That is another way, but that is also renunciation in itself, non-attachment in itself. So that is the first four sentences.