The following is respectfully quoted from “The Way of the Bodhisattva” by Shantideva as translated by the Padmakara Translation Group and published by Shambhala:

Vigilance

1.

Those who wish to keep a rule of life

Must guard their minds in perfect self-possession.

Without this guard upon the mind,

No discipline can ever be maintained.

2.

Wandering where it will, the elephant of the mind,

Will bring us down to pains of deepest hell.

No worldly beast, however wild,

Could bring upon us such calamities.

3.

If, with mindfulness’ rope,

The elephant of the mind is tethered all around,

Our fears will come to nothing,

Every virtue drop into our hands.

4.

Tigers, lions, elephants, and bears,

Snakes and every hostile beast,

Those who guard the prisoners in hell,

All ghosts and ghouls and every evil phantom,

5. By simple binding of this mind alone,

All these things are likewise bound.

By simple taming of this mind alone,

All these things are likewise tamed.

6.

For all anxiety and fear,

All sufferings in boundless measure,

Their source and wellspring is the mind itself,

Thus the Truthful One has said.

7.

The hellish whips to torture living beings–

Who has made them and to what intent?

Who has forged this burning iron ground;

Whence have all these demon women sprung?

8.

All are but the offspring of the sinful mind,

Thus the Mighty One has said.

Thus throughout the triple world

There is no greater bane than mind itself.

9.

If transcendent giving is

To dissipate the poverty of beings,

In what way, since the poor are always with us,

Have former buddhas practiced perfect generosity?

10.

The true intention to bestow on every being

All possessions–and fruits of such a gift;

By such, the teachings say, is generosity perfected.

And this, as we may see, is but the mind itself.

11.

Where, indeed, could beings, fishes, and the rest

Be placed, to shield them from suffering?

Deciding to refrain from harming them

Is said to be the perfection of morality.

12.

The hostile multitudes are vast as space–

What chance is there that all should be subdued?

Let but this angry mind be overthrown

And every foe is then and there destroyed.

13.

To cover all the earth with sheets of hide–

Where could such amounts of skin be found?

But simply wrap some leather round your feet,

And it’s as if the whole earth had been covered!

14.

Likewise, we can never take

And turn aside the outer course of things.

But only seize and discipline the mind itself,

And what is there remaining to be curbed?

15.

A clear intent can fructify

And bring us birth in lofty Brahma’s realm.

The acts of body and of speech are less–

They do not generate a like result.

16.

Recitations and austerities,

Long though they may prove to be,

If practiced with distracted mind,

Are futile, so the Knower of the Truth has said.

17.

All who fail to know and penetrate

This secret of the mind, the Dharma’s peak,

Although they wish for joy and sorrow’s end,

Will wander uselessly in misery.

18.

This is so, and therefore I will seize

This mind of mine and guard it well.

What use to me so many harsh austerities?

But let me only discipline and guard my mind!

19.

When in wild, unruly crowds

We move with care to shield our broken limbs,

Likewise when we live in evil company,

Our wounded minds we should not fail to guard.

20.

For if I carefully protect my wounds

Because I fear the hurt of cuts and bruises,

Why should I not guard my wounded mind,

For fear of being crushed beneath the cliffs of hell?

21.

If this is how I act and live,

Then even in the midst of evil folk,

Or even with fair women, all is well.

My diligent observance of the vows will not decline.

22.

Let my property and honor all grow less,

And likewise all my health and livelihood,

And even other virtues–all can go!

But never will I disregard my mind.

23.

All you who would protect your minds,

Maintain awareness and your mental vigilance.

Guard them both, at the cost of life and limb–

Thus I join my hands, beseeching you.

24.

Those disabled by ill health

Are helpless, powerless to act.

The mind, when likewise cramped by ignorance,

Is impotent and cannot do its work.

25.

And those who have no mental vigilance,

Though they may hear the teachings, ponder them or meditate,

With minds like water seeping from a leaking jug,

Their learning will not settle in their memories.

26.

Many have devotion, perseverance,

Are learned also and endowed with faith,

But through the fault of lacking mental vigilance,

Will not escape the stain of sin and downfall.

27.

Lack of vigilance is like a their

Who slinks behind when mindfulness abates,

And all the merit we have gathered in

He steals, and down we go to lower realms.

28.

Defilements are a band of robbers

Waiting for their chance to bring us injury.

They steal our virtue, when their moment comes,

And batter out the life of happy destinies.

29.

Therefore, from the gateway of awareness

Mindfulness shall not have leave to stray.

And if it wanders, it shall be recalled,

By thoughts of anguish in the lower worlds.

30.

In those endowed with fortune and devotion,

Mindfulness is cultivated easily–

Through fear, and by the counsels of their abbots,

And staying ever in their teacher’s company.

31.

The buddhas and bodhisattvas both

Possess unclouded vision, seeing everything:

Everything lies open to their gaze,

And likewise I am always in their presence.

32.

One who has such thoughts as these

Will gain devotion and a sense of fear and shame.

For such a one, the memory of Buddha

Rises frequently before the mind.

33.

When mindfulness is stationed as a sentinel,

A guard upon the threshold of the mind,

Mental scrutiny is likewise present,

Returning when forgotten or dispersed.

34.

If at the outset, when I check my mind,

I find some fault or insufficiency,

I’ll stay unmoving, like a log,

In self-possession and determination.

35.

I shall never, vacantly,

Allow my gaze to wander about,

But rather with a focused mind

Will always go with eyes cast down.

36.

But that I might relax my gaze,

I’ll sometimes raise my eyes and look around.

And if some person stands in my sight,

I’ll greet him with a friendly word of welcome.

37.

And yet, to spy the dangers on the road,

I’ll scrutinize the four directions one by one.

And when I stop to rest, I’ll turn my head

And look behind me, back along my path.

38.

And so, I’ll spy the land, in front, behind,

To see if I should go or else return.

And thus in every situation,

I shall know my needs and act accordingly.

39.

Deciding on a given course,

Determining the actions of my body,

From time to time I’ll verify

My body’s actions, by repeated scrutiny.

40.

This mind of mine, a wild and rampant elephant,

I’ll tether that sturdy post: reflection on the Teaching.

And I shall narrowly stand guard

That it might never slip its bonds and flee.

41.

Those who strive to master concentration

Should never for an instant be distracted.

They should constantly investigate themselves,

Examining the movements of their minds.

42.

In fearful situations, times of celebration,

One may desist, when self-survey becomes impossible.

For it is taught that in the times of generosity,

The rules of discipline must be suspended.

43.

When something has been planned and started on,

Attention should not drift to other things.

With thoughts fixed on the chosen target,

That and that alone should be pursued.

44.

Behaving in this way, all tasks were performed,

And nothing is achieved by doing otherwise.

Afflictions, the reverse of vigilance,

Can never multiply if this is how you act.

45.

And if by chance you must take part

In lengthy conversations worthlessly,

Or if you come upon sensational events,

Then cast aside delight and taste for them.

46.

If you find you’re grubbing in the soil,

Or pulling up the grass or tracing idle patterns on the ground,

Remembering the teachings of the Blissful One,

In fear, restrain yourself at once.

47.

When you feel the wish to walk about,

Or even to express yourself in speech,

First examine what is in your mind.

For they will act correctly who have stable minds.

48.

When the urge arises in the mind

To feelings of desire or wrathful hate,

Do not act! Be silent, do not speak!

And like a log of wood be sure to stay.

49.

When the mind is wild with mockery

And filled with pride and haughty arrogance,

And when you want to show the hidden faults of others,

To bring up old dissensions or to act deceitfully,

50.

And when you want to fish for praise,

Or criticize and spoil another’s name,

Or use harsh language, sparring for a fight,

It’s then that like a log you should remain.

51.

And when you yearn for wealth, attention, fame,

A circle of admirers serving you,

And when you look for honors, recognition–

It’s then that like a log you should remain.

52.

And when you want to do another down

And cultivate advantage for yourself,

And when the wish to gossip comes to you,

It’s then that like a log you should remain.

53.

Impatience, indolence, faint heartedness,

And likewise haughty speech and insolence,

Attachment to your side–when these arise,

It’s then that like a log you should remain.

54.

Examine thus yourself from every side.

Note harmful thoughts and every futile striving.

Thus it is that heroes in the bodhisattva path

Apply the remedies to keep a steady mind.

55.

With perfect and unyielding faith,

With steadfastness, respect, and courtesy,

With modesty and conscientiousness,

Work calmly for the happiness of others.

56.

Let us not be downcast by the warring wants

Of childish persons quarreling.

Their thoughts are bred from conflict and emotion.

Let us understand and treat them lovingly.

57.

When doing virtuous acts, beyond reproach,

To help ourselves, or for the sake of others,

Let us always bear in mind the thought

That we are self-less, like an apparition.

58.

This supreme treasure of a human life,

So long awaited, now at last attained!

Reflecting always thus, maintain your mind

As steady as Sumeru, king of mountains.

59.

When vultures with their love of flesh

Are tugging at this body all around,

Small will be the joy you get from it, O mind!

Why are you so besotted with it now?

60.

Why, O mind, do you protect this body,

Claiming it as though it were yourself?

You and it are each a separate entity,

How ever can it be of use to you?

61.

Why not cling, O foolish mind, to something clean,

A figure carved in wood, or some such thing?

Why do you protect and guard

An unclean engine for the making of impurity?

62.

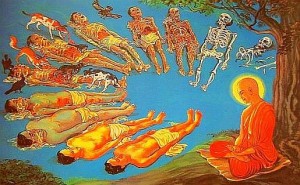

First, with mind’s imagination,

Shed the covering of skin,

And with the blade of wisdom, strip

The flesh from bony frame.

63.

And when you have divided all the bones,

And searched right down amid the very marrow,

You should look and ask the question:

Where is “thingness” to be found?

64.

If, persisting in the search,

You find no underlying object,

Why still cherish–and with such desire–

The fleshy form you now possess?

65.

Its filth you cannot eat, O mind:

Its blood likewise is not for you to drink;

Its innards, too, unsuitable to suck–

This body, what then will you make of it?

66.

As second best, it may indeed be kept

As food to feed the vulture and the fox.

The value of this human form

Lies only in the way that it is used.

67.

Whatever you may do to guard and keep it,

What will you do when

The Lord of Death, the ruthless, unrelenting,

Steals and throws it to the birds and dogs?

68.

Slaves unsuitable for work

Are not rewarded with supplies and clothing.

This body, though you pamper it, will leave you–

Why exhaust yourself with such great labor?

69.

So pay this body due remuneration,

But then be sure to make it work for you.

But do not lavish everything

On what will not bring perfect benefit.

70.

Regard your body as a vessel,

A simple boat for going here and there.

Make of it a wish-fulfilling gem

To bring about the benefit of beings.

71.

Thus with free, untrammeled mind,

Put on an ever-smiling countenance.

Rid yourself of scowling, wrathful frowns,

And be a true and honest friend to all.

72.

Do not, acting inconsiderately,

Move furniture and chairs so noisily around.

Likewise do not open doors with violence.

Take pleasure in the practice of humility.

73.

Herons, cats, and burglars

Go silently and carefully;

This is how they gain what they intend.

And one who practices this path behaves likewise.

74.

When useful admonitions come unasked

To those with skill in counseling their fellows,

Let them welcome them with humble gratitude,

And always strive to learn from everyone.

75.

Praise all who speak the truth,

And say, “Your words are excellent.”

And when you notice others acting well,

Encourage them in terms of warm approval.

76.

Extol them even in their absence;

When they’re praised by others, do the same.

But when the qualities they praise are yours,

Appreciate their skill in knowing qualities.

77.

The goal of every act is happiness itself,

Though, even with great wealth, it’s rarely found.

So take your pleasure in the qualities of others.

Let them be a heartfelt joy to you.

78.

By acting thus, in this life you’ll lose nothing;

In future lives, great bliss will come to you.

The sin of envy brings not joy but pain,

And in the future, dreadful suffering.

79.

Speak with honest words, coherently,

With candor, in a clear, harmonious voice.

Abandon partiality, rejection, and attraction,

And speak with moderation, gently.

80.

And catching sight of others, think

That it will be through them

That you will come to buddhahood.

So look on them with open, loving hearts.

81.

Always fired by highest aspiration,

Laboring to implement the antidotes,

You will gather virtues in the fields

Of qualities, of benefits, of sorrow.

82.

Acting thus with faith and understanding,

You will always undertake good works.

And in whatever actions you perform,

You’ll not be calculating, with your eye on others.

83.

The six perfections, giving and the rest,

Progress in sequence, growing in importance.

The great should never be supplanted by the less,

And it is others’ good that is the highest goal.

84.

Therefore understand this well

And always labor for the benefit of beings.

The far-seeking masters of compassion

Permit, to this end, that which is proscribed.

85.

Eat only what is needful;

Share with those who have embraced discipline.

To those, defenseless, fallen into evil states,

Give all except the three robes of religion.

86.

The body, apt to practice sacred teaching,

Should not be harmed in trivial pursuits.

It this advice is kept, the wishes of all beings

Will swiftly and completely be attained.

87.

They should not give up their bodies

Whose compassion is not pure and perfect.

But let them, in this world and those to come,

Subject their bodies to the service of the supreme goal.

88.

Do not teach to those without respect,

To those who like the sick wear cloths around their heads,

To those who proudly carry weapons, staffs or parasols,

And those who keep their hats upon their heads.

89.

Do not teach the vast and deep to those

Upon the lower paths, nor, as a monk,

To women unescorted. Teach with equal honor

Low and high according to their path.

90.

Those suited to the teachings vast and deep,

Should not be introduced to lesser paths.

But basic practice you should not forsake,

Confused by talk of sūtras nd of mantras.

91.

Your spittle and your toothbrushes,

When thrown away, should be concealed.

And it is wrong to foul with urine

Public thoroughfares and water springs.

92.

When eating do not gobble noisily,

Nor stuff and cram your gaping mouth.

And do not sit with legs outstretched,

Nor rudely rub your hands together.

93.

Do not sit upon a horse, on beds or seats,

With women of another house, alone.

All that you have seen, or have been told,

To be offensive–this you should avoid.

94.

Not rudely pointing with your finger,

But rather with a reverent gesture showing,

With the whole right hand outstretched–

This is how to indicate the road.

95.

Do not wave your arms with uncouth gestures.

With gentle sounds and finger snaps

Express yourself with modesty–

For acting otherwise is impolite excess.

96.

Lie down to sleep with posture and direction

Of the Buddha when he passed into nirvāna.

And first, with clear resolve,

Decide that you’ll be swift to rise again.

97.

The bodhisattva’s acts

Are boundless, as the teachings ay,

And all these practices that cleanse the mind

Embrace–until success has been attained.

98.

Reciting thrice, by day, by night,

The Sūtra in Three Sections,

Relying on the buddhas and the bodhisattvas,

Purify the rest of your transgressions.

99.

And therefore in whatever time or place,

For your own good and for the good of others,

Be diligent to implement

The teachings given for that situation.

100.

There is indeed no virtue

That the buddha’s offspring should not learn.

To one with mastery therein,

There is no action destitute of merit.

101.

Directly, then, or indirectly,

All you do must be for others’s sake.

And solely for their welfare dedicate

Your actions for the gaining of enlightenment.

102.

Never, at the cost of life or limb,

Forsake your virtuous friend, your teacher,

Learned in the meaning of Mahāyāna,

Supreme in practice of the bodhisattva path.

103.

For thus you must depend upon your guru,

And you will find described in Shrī Sambhava’s life,

And elsewhere in the teachings of the Buddha:

These be sure to study, reading the sūtras.

104.

The training you will find described

Within the sūtras. Therefore read and study them.

The Sūtra of the Essence of the Sky–

This is the text that should be studied first.

105.

The Digest of All Disciples

Contains a detailed and extensive explanation

Of all that must be practiced come what may.

So this is something you should read repeatedly.

106.

From time to time, for the sake of brevity,

Consult the Digest of the Sūtras.

And those two works pursue with diligence.

The noble Nāgārjuna has composed.

107.

Whatever in these works is not proscribed

Be sure to undertake and implement.

And what you see there, perfectly fulfill,

and so safeguard the minds of worldly beings.

108.

To keep a guard again and yet again

Upon the state of actions of our thoughts and deeds–

This and only this defines

The nature and the sense of mental watchfulness.

109.

But all this must be acted out in truth,

For what is to be gained by mouthing syllables?

What invalid was ever helped

By merely reading in the doctor’s treatises?