The following is respectfully quoted from “Reborn in the West” by Vicki Mackenzie:

Before receiving her bodhisattva vows she had told Penor Rinpoche of her own vow that she was teaching to her students: ‘I dedicate myself to the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings. I offer my body, speech and mind in order to accomplish the purpose of all sentient beings. I will return in whatever form necessary, under extraordinary circumstances, to end suffering. Let me born in times unpredictable, in places unknown, until all sentient beings are liberated from the cycle of death and rebirth.

Taking no thought for my comfort or safety, precious Buddha make me a pure and perfect instrument by which the end of suffering and death in all forms might be realized. Let me achieve perfect enlightenment for the sake of all beings. And then, by my hand and heart alone, may all beings achieve full enlightenment and perfect liberation.’

Penor Rinpoche had rocked to and fro in unbridled mirth, slapping his thigh in amusement. She had replicated, almost exactly the same prayers that Tibetan lamas spoke. It was another proof of her identity.

He handed her another certificate, authorizing her to teach. ‘This is important,’ he said. ‘People will say you haven’t been studying the dharma, that they have never heard of you. They will not understand. With this paper no one will doubt that you are capable of teaching the dharma.’

Penor Rinpoche went on to tell Jetsunma a little about her famous ‘predecessor’. The first Ahkön Lhamo was the direct student of Tertön Migyur Dorje, a famous revealer of secret teachings, he said. She was a great dakini and spent decades in retreat, only coming down from her cave to help her brother with his monastery. Otherwise people would go to her to receive healing and teaching.

I asked Jetsunma if she were curious to find out more about Ahkön Lhamo or had any memories of the yogini who had lived in Tibet in 1665 and had inspired a religious order that had survived to this present day.

‘I discovered she was pretty wild,’ she replied. ‘She stayed up in her cave and looked pretty wretched, with her hair sticking out all over the place,’ she said, picking up her own unruly locks. ‘She was a crazy yogini type. Some things never change! There was no water in her cave, of course, and she never bathed. Her clothes were rotting on her. But people said whenever they went to her cave it would smell like perfume. Penor Rinpoche told me that people would give her turquoise, gold and coral, but she would refuse it. She was probably holding out for gifts she could accept, like hair-driers! She was probably waiting for electricity to be put into her cave and she could have central heating!’ she joked.

‘As for any memories, I don’t like to make any fuss about the inner experience I have. I can tell you I have some awareness of it, but it’s pretty “Swiss cheesy”. I am curious. I want to go back to Tibet, to see the cave where she practiced. Gyaltrul Rinpoche, the reincarnation of Kunzang Sherab who is now in Oregon, said that when he went back to Tibet he remembered a lot. It’s as though the airways are clearer there.’

There is at least one concrete link between this latter-day bodhisattva, the girl from Brooklyn, and the seventeenth century Tibetan yogini who had helped found a Buddhist lineage. Ahkön Lhamo’s skull, or part of it, is still in existence. It bears an unmistakable hallmark of sanctity. On its top is etched the holy sanskrit syllable ‘Ah’.

The story goes like this. When the first Ahkön Lhamo passed away, they prepared a pyre to cremate her and duly put the body on it. When the last vestige of flesh was burnt away, the skull rose up in the air in front of hundreds of people and flew about a mile before landing at the Palyul monastery, at the foot of her brother Kunzang Sherab’s throne. This was considered the final ultimate display of Ahkön Lhamo’s power and spiritual accomplishments. The great dakini, who was already known for the many miracles she performed, had revealed her true greatness.

The skull became a most treasured relic and was used as a kapala, and instrument used in ritual ceremonies for holding nectar. It remained intact until in the mid-twentieth century the invading Chinese hacked to pieces everything of spiritual significance, including the precious kapala at the Palyul monastery. A lay person saw a piece of the skull among the rubble and, hiding it in his clothes, took it to safety. It was some years before Penor Rinpoche got word that at least part of the holy relic had survived.

The was a vast gap in time between 1660 and 1949, when the present Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo was born. I asked her the same question I had asked Tenzin Sherab. What lives did she think she had been living in between?

‘I think there were other incarnations, but as Penor Rinpoche told me, they don’t keep track of women. It wasn’t because they were prejudiced against women’s wisdom. In fact, dakinis are the primordial wisdom beings and are held in very high regard. Generally, though, dakinis were not the lineage holders. They spent their lives in solitude, doing spiritual practices. Penor Rinpoche says, and I feel, that there have been many incarnations.

But this present one, as the American woman doing it ‘her way’ as undoubtedly she always had, was the life that was to capture widespread attention. Jetsunma left the United States as a married woman, mother of two and teacher of New Age metaphysics with a bent for worldwide caring, and returned a recognized tulku, a reincarnate lama. For her students this took some adjustment. While they had been happily following the teachings of a woman whom they treated as their equal, they now had to contend not only with a ‘Buddhist’ but also with someone whose rank placed her on an entirely different footing. There was protocol to observe, a new language to learn for the same concepts they had learnt, and the mantle of an old and established ‘religion’ from the East to adopt. Some disciples fell out, but most survived the transition.

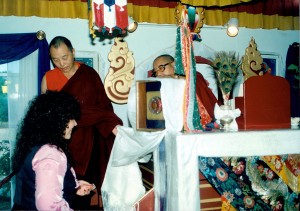

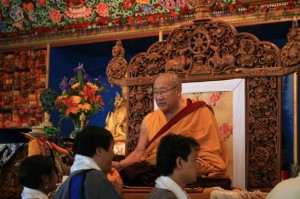

Whatever misgivings they might have had about the authenticity of their teacher’s new lofty reincarnate status, however, were completely dispelled when Penor Rinpoche came to see them for the second time in 1988. “He arrived at Poolesville with twelve monks in attendance and conferred the Rinchen Terzod, the revealed teachings of the great Padma Sambhava to all member of KPC. It was the first time he had ever performed the task in his lifetime, and the first time in North America”.

He then conducted an official enthronement of Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo. News of the thirty-nine-year-old woman who had been recognized as the reincarnation of a famous Tibetan yogini reached the media. Newspaper reporters and television crews descended on KPC. ‘Meet Ahkön Norbu Lhamo, Tibetan Saint,’ blazed the front-page headline of the International Herald Tribune. ‘The Unexpected Incarnation’ cried the Washington Post. She appeared in the popular People magazine. Leading Japanese and German magazines ran articles on her. This was when my own journalist’s antennae, primed for good stories, must have picked up the importance of the event and stored it away for later use.