The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “The Lama Never Leaves”

Whenever we are on the path and we have a spiritual friend in the form of a teacher, whether it is on the earlier path of Theravadin Buddhism or whether we have a spiritual guru who is from the Vajrayana point of view, a very profound friend who one can expect will mingle with our lives and hopefully mingle with our mindstreams, and give us the appropriate information in order to practice the path, there is one set of instructions that is almost always given in one way or another. And so I’d like to give these instructions. They are about gathering and accomplishing “merit”…or meritorious activity.

Here in our society, we are taught in a materialistic way. We are taught that of course if we get education we will make money. If we make money, we will get things. If we get things, we will be happy and we can pass those things on to our children who hopefully will be happy also. And that’s the idea that we have in this society about material things.

Very rarely do our parents teach us about profitable conduct. We’re taught about how to live profitably. Hopefully, if we had good parenting, they taught us about how to keep a bank account and all of those passages of adulthood that we learn about. But nowadays, it has become much less popular, unfortunately, for parents to teach us profitable conduct; in other words, how to act, how to present oneself, how to hold oneself, what deeds to act upon and so forth, that will bring us happiness and joy. We in fact, in growing up, we are not really taught that acting in a certain way will bring us happiness or joy; or making offerings in a certain way, or certain kinds of conduct. Generally what happens is the child imitates the parent. Many times the parent, like any other samsaric being, is neurotic and we see them acting neurotically in their relationships, and we see that it’s like a roll of the dice. According to how we act, half the time it produces happiness, and half the time it doesn’t. And sometimes when we’re in a real spiral…that means the downward kind…we can experience a great deal of neuroses and our children will watch that habitual patterning and they will pattern themselves after it. It’s natural. It’s hard-wired in children to do that. And of course in this day and age, it seems like we have lost touch with what it is that actually creates happiness. We are so confused in our minds…we’re in such turmoil…we’re always grasping and grabbing and trying and often we’re working very hard at it. It’s not that we’re lazy. We don’t just lay around all day. We’re often working very hard at things that ultimately produce no good result. Pursuing endless distractions, the Buddhas have called it.

And so, we turn to the people of authority in our lives and we look to them for guidance. Well, we look to the government and the government says, “Let’s cut down on social services, screw the poor people, we’ll go to war!” So maybe that’s not so good.

So then we look at our parents…and let’s see, parent’s are on maybe second or third marriage, and they’re very much trying to be happy but they don’t know how to be happy and the parents are in as much turmoil as perhaps the child is.

And then the child turns to the teachers and even religious figures. And if the religious figure is not enlightened, often times they are lead down horrible paths; perhaps even abusive paths where they are taught some strict dogma that has no relationship to anything really; or in the worst case scenario, they are used and abused by a religious figure of authority.

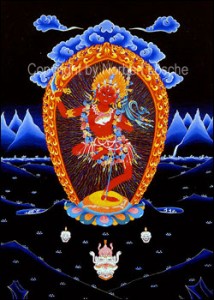

So where do we actually go to understand what it is the Buddha taught about cause and result…because this is where the Buddha really shone…showed his immense wisdom, his immense capacity. …Is that not only Shakyamuni Buddha, himself, but every teacher and lama that has studied his teachings, followed his ways and accomplished. And all the teachers yet to come that revealed Terma, including Guru Rinpoche and those that were Treasure Revealers later on, each in their own way, taught us Proper Conduct.

Proper Conduct is actually part of our Ngondro practice in which we learn to turn the mind toward Dharma. And that doesn’t mean…what do you call it when somebody…a person that sings the rap of a certain company and…public relations, right. It’s not like that. Our teachers actually indicate to us how we should live and actually that’s one of the signs of the Buddha is that the Buddha comes to the earth and shows us how to live because we are living in confusion. We have not been taught of cause and effect. And this is one thing that Lord Buddha really taught about was cause and result. And he said that, if spiritual thinking isn’t reasonable and logical, that is, if one cannot think it through first before one decides to really open the heart in faith, then we should think again.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved