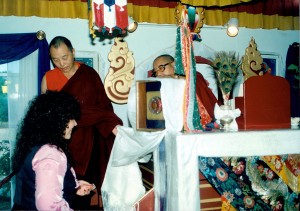

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Love Now, Dzogchen Later”

Ngondro purifies the five senses to such a degree that many of the gross defilements. The ones that you meet up in your life where you are happily going along the road of life and you get punched in the face by karma. Those obstacles. You know. They purify some of that and they keep that sort of thing from happening or they make it happen more benignly pacified is the idea. And then accumulation of the Three Roots stabilizes the mind. Begins to ripen the mind. At that time we are trying to accomplish the Vajra confidence of the deities, their very pure qualities. Their ability to establish virtue. Their ability to accomplish view. All of these things are accomplished through this recitation. But nowadays, we don’t even have to do that. We go to Tsa Lung. And we don’t even have to finish Tsa Lung. Then we can go to Trekchod, and then we can go to Togyal. I think that is right. We don’t really have to graduate. And you have to ask yourself at this point. What has changed? Did His Holiness change?

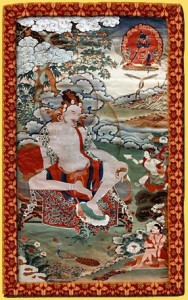

I think of His Holiness like the Copper Mountain. Our perception of the Copper Colored Mountain may change. It may be connected to our own capability but does the Copper Colored Mountain ever change? No. It is absolutely empty of self-nature and yet spontaneously accomplished. Figure that one out. So, there is no fault here. The fault is not with His Holiness. His Holiness made a decision based on the times and I understand his decision. It is not for me to agree or disagree, but I absolutely understand what his method is. But the thing that I want to express to you is that it puts the responsibility on us. To accomplish when we are not with His Holiness what we have to accomplish in order to make what he is teaching us next worthwhile.

One of the worst things that I have seen happen, that is a terrible result, and indeed it is not unusual in the sense that it is different from the way the world is acting now. But still I have to say that it is not a good result and that is that most people on the path blow right by giving rise to the Bodhicitta. Giving rise to the great compassion, to the way that actually is the very essence of awakening. The Bodhicitta. Now, His Holiness always teaches about Bodhicitta. He never denies an opportunity. Never abandons an opportunity. He teaches about the Bodhicitta every time. Like for instance when he starts to give a teaching or he starts to do a practice, often he will remind us to establish our motivation and the Khenpos will always say that we must establish our motivation or that we must understand that we are hearing this teaching not just to hang out here or that we are doing some practice not just because we are bored or for some other self-oriented reason. But the only valid, righteous and appropriate motivation to accomplish Dharma is for the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings. So, we can repeat that back. We’ve heard this so many times. And we can say if I say to you, “Why are you doing this practice?” You’ll say, “Oh, liberation and salvation of all sentient beings.” We’ve heard this so many times that we can parrot it back. Sort of like a Malaccan Cockatoo or an African Gray. But have we really given rise to the Bodhicitta? Have we really accomplished it? Have we worked really clean? Thank you! Somebody said no. I appreciate that. You know? Have we worked cleanly and purely with our motivation? Do we tutor ourselves on our motivation everyday, every moment? And when we have choices to make, do we reestablish the motivation so that we can make the correct choices by saying, “Thus for the sake of sentient beings, I will open this altar, close this altar, pray, circumambulate, do my practice, study some Dharma. Benefit sentient beings in some way. Feed the hungry. Heal the sick. Walk a dog.“ Anything! Anything. Do we remind ourselves that that is our reason for taking our next breath? That other than giving rise to compassion, giving rise to the mind of Bodhicitta which by the way, is the pure awakened state, our primordial wisdom nature, that that is the reason for anything that we do. And should remain so. And if we do not have the proper karma to be born in a monastery amongst many learned monks and nuns and many learned Khenpos, and lamas and Rinpoches, then we must accept that as our karma. And shouldn’t leave ourselves to say, “Oh those poor guys. They have to work for years trying to accomplish some Dharma and all they get is a couple of maroon colored sheets and a rug. And you know, they just stay there in the Monastery. And gee, I get to hang out here in America with cars, and TVs, and you know, stuff. I have a great house. And I can buy another car if I want. And you know there are so many things that I can do do do. And have have have have. And yet I get some Dzogchen. Whoopee! I must be the most fabulous person in the world. “

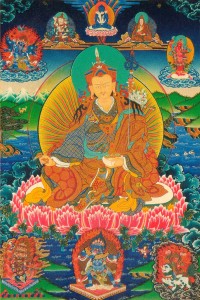

Unfortunately, our response to being given this great blessing is a little more like the whoopee part than it is the honest internal watchfulness that makes us ask ourselves, “Have I given rise to the Bodhicitta? Have I accomplished good qualities?” I mean when you practice the root deities, the Three Roots you accumulate so many repetitions of the mantra and you put so much energy into visualizing their different hand held implements and even their posture, which means something. The handheld implement and the posture are the very display of the deities’ excellent qualities and activities. So, we practice many repetitions of the mantra of the root deity. And we think now we have accomplished the qualities of the root deity. What are the qualities of the root qualities of the root deity? We study the hand implements. We study the posture, and we begin to inhabit those qualities. We begin to display those qualities. We accept those qualities. We habituate towards those qualities and even one of the qualities that we habituate toward is Vajra pride.

Vajra pride which is different from American pride. American pride is the bullshit that knocks you off the path. Vajra pride is the confidence in the method. Confidence in the method through meditating on Shunyata and giving rise to the deity. And so there is the confidence. Not having practiced mantra like that. Not having gone through those different accomplishments, we instead have given rise to ordinary pride. And ordinary pride is stupid pride. It tells us to argue with the elder sangha members, lamas, and Khenpos, thinking that we know better, or to make up our own religion. Or to just do it the way we want to, or to just self cherish. To meditate on self-cherishing, ego cherishing, which is giving rise to the ordinary pride and back to that ordinary cycle. But when we accomplish the deity, something different rises up. And then when we move on to the other levels, we move on with Vajra confidence and unshakeable Bodhicitta – compassion.

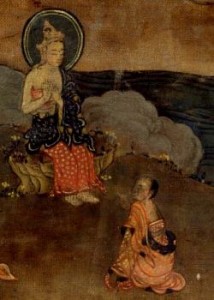

Now, when that foundation is properly laid, and we have properly practiced Bodhicitta, and we have properly accumulated mantra and we have purified our senses through the Ngondro, then when we are introduced to Dzogchen. The mind is matured. The blessing of the lama, particularly if we have accomplished purely the accumulation of Vajra Guru mantra within the context of Guru Yoga in Ngondro. And what is it, 1.5 million of those? Or 1.2, I forget. Huh? 1.2? Thank you. She knows but did you do it? Oh see! Yeah. So, after you accomplish that many Vajra Guru mantras in the context of Guru Yoga, you have changed. Your capability is different.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved