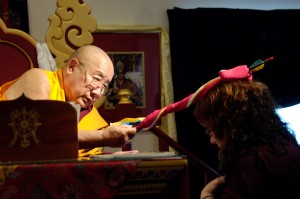

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Marrying a Spiritual Life with Western Culture”

Our job then is to get in, to make this faith more than a formalized external thing just like an exoskeleton. The only way to get in is by really understanding it, by really going through the process that empowers you, to see what the truth actually is. For instance, we’re told that cause and effect is for real. Cause and effect should be blatantly obvious to us by this time because most of us here are above five years old. But we don’t get it. Lord Buddha tells us that cause and effect really matter. If you engage in virtuous, loving, generous, kind acts, the results will be love, happiness, fulfillment, higher rebirth, all of these kinds of things. That seems pretty reasonable to me.

But if we don’t go through what it takes to truly understand this on a deep level, we end up approaching even this very visible piece of truth by saying, “Oh this is another thing I have to learn.” I’ve seen my students do this—from my very oldest to the brand new ones. “From now on I’m going to do good things, because good things will get good results and I’m going to be happy. Okay. Let’s see now. It’s 7 o’clock in the morning. I will be out of bed by 7:15. Can I get a good thing done by 7:20?” This is the way that we think. It’s by rote. A chicken can do this! A parrot that can be taught to talk can learn these rules. But where is the heart of the parrot?

What if we could hear the Buddha’s teaching and say, “This is an amazing wisdom that has come into the world. The Buddha organizes this wisdom and says to us, ‘Virtuous actions produce excellent results.’” What if we went through the process of really looking at this? What if we really tried to connect the dots? What if we looked at our own life experience? Yes, it’s hard to do. We know that. The reason it’s hard to do is that in order for you to examine what virtuous conduct looks like and how it relates to result, you have to determine what is virtuous conduct and what is non-virtuous conduct. In order to do that you have to face some terrible truths about yourself—for example, that you don’t always engage in virtuous conduct. The minute we get near that sucker we back off fast. Because isn’t religion supposed to make us feel better? Well, yes, if it’s an opiate. Well, yes, if it’s a drug—one of your many drugs.

Religion can be compared more to exercise. When we first start to exercise, especially nowadays, we join a club and get an outfit. (I have some killer workout outfits, I want you to know.) We get an outfit and everything matches, the socks, the headband. Or else we jock out about it. Maybe everything doesn’t match, but it’s all cool. And then we get in there, and we don’t work out or exercise because it feels good to lift vast amounts of weight over and over again. Not at first. In fact, at first there’s a lot of pain. You get on those machines, and the next thing you know you can’t move. So starting never feels good, but, afterwards—when you’re in shape and your body is tuned up and you’re strong—you feel great! It’s an organic thing. It benefits all your systems. It comes up from inside of you. It changes everything about your life. It feels great. But initially, no. Most people stop with that initial stuff, don’t they? The minute it doesn’t feel good, that’s when they stop.

We do the same thing with religion. Can you see that? We go into it with an outfit, and we do it until it’s a little uncomfortable, such as changing something about our lives or seeing something. Then we’re out of there, because we have the “don’t wannas.” We don’t wanna; it doesn’t feel good. We think, “I thought this was going to make me happy, and it really doesn’t. It’s kind of depressing to think about reality. I don’t want to.”

Now let’s look at a person who moves into making exercise part of their lives. You do it in a more directly related way. You learn something about it. You learn about the physiology of exercise. You learn that there are certain problems your body has that it doesn’t have when you exercise. Well, that’s one thing that will empower you to keep on going: You go for that goal of producing a certain result. Have you ever thought of that in your practice? Producing a certain result, instead of just putting in your time? There is a difference. With exercise we get to a certain point where we just begin to see—because we’re looking inside of ourselves and we’re looking in the mirror—that there is some result. The first time you see a result it can be a life-changing experience, if you work to integrate it into your life.

It’s just exactly like that with religion. Initially, you have to change. Change is not comfortable. We already know this. So initially you change and then after that you begin to connect the dots. You begin to see some cause and effect relationships. You begin to see that virtuous behavior actually does make you feel pretty good, and you explore that. You don’t take it for granted like a big dope. You work it out in your mind—work the numbers, work the equations. What feels good? Does it feel good to be in charge of your own internal progress? I think so. It doesn’t feel good to walk through life and just let life hit you like a truck. It feels good to walk through life in my practice, knowing in my heart that I am deeply empowered by this direct intimate relationship to spirituality. I know what kindness tastes like. I can see direct results from certain kinds of behavior patterns, behavior changes. I can see them directly in my mind. I feel comfortable with that. How is it that Tibetan monks have the same restrictions as our ordained and they are so much more comfortable with them? How is it that Tibetan lay people feel so much more comfortable with their lives? It’s because they have some kind of direct experience that makes it sensible and realistic and reasonable to conduct themselves in a certain way.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved