Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

The True Meaning of Friendship

The following is a full length video teaching offered by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo at Kunzang Palyul Choling:

Friends are so precious in our lives. How can we maximize these relationships to move both our friends and ourselves toward enlightement.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved

In a Dream

In a dream I remember that I forgot what I remembered

I knew that I knew it was a dream.

I know I can stand still, in full presence and awaken

How odd that our uncontrived Primordial Nature dances with SO MANY mirrors, all sizes and shapes.

Splendid and devastating!

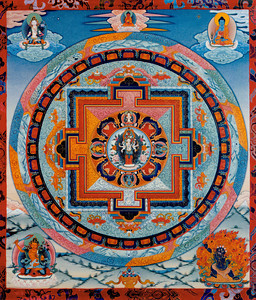

OM MANI PEDME HUNG

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

Qualities: excerpts from Palyul Clear Light

“When one has some little bit of quality or knowledge, one should not think pridefully ‘Oh, I am so great’. Then one’s quality and knowledge will degenerate, and in the future it will be even more difficult to give rise to these kinds of qualities and knowledge”

The previous #quote is from Kyabje HHPenor Rinpoche With thanks to Kenchen Tsewang Gyatso and PALYUL CLEAR LIGHT

THE STAINLESS ESSENCE TANTRA says: Merit accumulated from prayer. Offering, and making praises before the image of your Lama is infinate and countless. Merely seeing him cleanses bad karma; merely hearing his words generates positive qualities; merely rembering him merges your mind with his. That which is very hard to find in ten million eons is attained in an instant. All these qualities come from the Lama!

The Stainless Essence Tantra thanks to Palyul Clear Light.

OMG! My Kid is a Mystic!

An excerpt from Marrying Spiritual Life with Western Cultureby Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

As many of you know, I like to climb the same mountain that you like to climb – the mountain of wisdom or understanding – so that we can get to the top and really have the full vista of understanding. I find its best to climb the mountain not in a linear way, but in a way that opens up to us true meaning on a conceptual level. It’s a good thing to climb that mountain from every possible angle you can think of because on each side there will be a different experience of going up the mountain. One can truly understand the mountain by moving in those various ways as opposed to having only one narrow means of approach.

In order to broaden and to deepen, then, one has to have the intention to really know and understand more deeply, so that Dharma will be real and focused and meaningful and will carry weight in one’s life. That’s what I’d like to talk about today. In order to do so, I’d like to talk about where we’re coming from and how our culture is different from a culture in which the Buddha naturally appeared and naturally emanated and naturally gave rise to certain teachings. The Buddha did not appear in Missouri – not in the way we understand. Although in truth the Buddha is everywhere in Missouri, the historical Buddha did not appear in Missouri or Indiana or Brooklyn, not in the same way. The original teachings, the path of Dharma that we practice, was brought to us by Lord Buddha himself.

The Dharma began in India, in a culture that is very different from ours. It’s where Lord Buddha appeared. Even if it is not the most potent religion in India now, it still has had some effect on shaping and forming that culture. Here in America there are religious factors that have shaped our culture, but they are different.

So I would like to examine some of the ways in which the cultures are different, just briefly enough to have a certain idea that we can examine for ourselves. The best thing to do is to look at these cultures today, with just an idea of where they came from and how they progressed. Culture in America today is materialistically oriented. We are a culture of attainers. We accumulate things. We are given a definition of success that is handed down from generation to generation and, oddly enough, it has more to do with substance than it has to do with spirit; more to do with material gain or loss than it ever has to do with joy. (Joy—what a concept!) When we are coming up, we are prepared and schooled to accomplish things that have to do with getting stuff – even if we study to become something that seems to be non-materialistically oriented, such as, for instance, a social worker.

You would think that a social worker would be looking at our culture with different eyes. You would think that a social worker would be asking, “Well, what are these social factors? How can we organize them into something that is meaningful and deep for us? How can we express within our culture the gamut of human expressions? How can we integrate it? How can we make it work for us? How can we discard those things that do not work for society?” Yes, that is some of the training of a social worker. But why does somebody become a social worker? And how do we approach that kind of thing? Well, we always think about how the job market is doing: “When I get out of school after I learn all of this, will I really be able to get a job?” And we think of ourselves as having an office, and we think of ourselves as having that little square on the office door that says, “You are somebody.” Then we think about whether that would be a really profitable occupation. So even if we were to approach something that could by its nature, be fundamentally non-materialistic, we approach it from a materialistic point of view. That’s something that is interesting and unique about our culture. It is so all-pervasive that it’s invisible, and you don’t really notice it until you go to other places.

If you really want to learn something about your culture, leave it and come back. If mainstream America does not have that kind of experience, they cannot really see very well what the factors are. It’s more difficult. So to leave one’s culture and have another taste or another experience gives one a sense of comparison.

We approach everything in a collecting or accumulating way, in a materialistic way. We measure success by material substance. Nobody’s parents tried to raise a great mystic because you wouldn’t do that to your kid in our society. You see what I’m saying? You want to prevent your kid from the dark night of the soul. You want to prevent your kid from the ambiguous, vague, cloudy, uncharted waters of mysticism. You want your kid to be on the straight and narrow: They know where to get a loaf of bread. They know how to put some butter on it. They know how to eat it. They know how to feed it to their kids. They know how to buy a car – that kind of thing. You want your kid to be prepared for that. You do not raise a mystic. A mystic is something you have to contend with in our society. It is an avocation that is fraught with suffering.

Now why is that? Well, partially because a mystic goes into a very deep sense of connection. In order to do that, the mystic has to plow through issues or plow through whatever it is that one plows through. The other reason why being a mystic is so darn painful is because no one has any respect for that kind of thing. A mystic in our society probably is a dreamer or a ne’er-do-well who can’t dress, who has no sense of self whatsoever, is socially inappropriate, and can’t figure out how to catch a cab. Or maybe a mystic is someone who is depressed, possibly should be on Prozac. These are the kind of things that we associate with a mystic’s life and that is why nobody has ever been encouraged to be like that. The idea of really profound deep mysticism scares the pattooties out of us.

But in another culture where that kind of ideal is held up as being something pure, something wonderful, something significant, one’s experience regarding mysticism is entirely different. There is a dignity and nobility about it. There is a sense that this is a worthwhile occupation. There is definitely less fear of having the freedom to utilize one’s life as a vehicle for true deep mysticism and spirituality. One of the reasons why it’s more comfortable and easier to get connected to it is because one isn’t socially ostracized.

Now the great thing about being a mystic in America is that, once you get to the point where you’re really good at it and somebody finds you and you can market it – – maybe write a book or two, maybe sell something that you’ve given rise to – then you can be a success. Mystics in our society can also be successful after they’re dead. I really don’t know why. If any of you know why, tell me. But while we’re alive, we don’t have too much hope.

So how does this affect our sense of personal practice, our sense of taking refuge? How does that connect with all of that? We find ourselves in a difficult situation. We are really limited, and we can’t see where the limitation is coming from. We don’t know how deep we can quest or search and how profoundly we can make the connection between the external environment – between the ordinary view – and our deepest most intimate spiritual nature. We feel somewhat limited in knowing how we can make that connection.

Let’s look again at some very important factors. Think of how we follow religion in our country. For the most part, here in the West, we believe religion is one of the many things that you should have in order to live a moral life. It’s part of the palette of a moral life. (This is kind of interesting, isn’t it?) Many of the people who are deeply religious according to our society’s capacity have adapted their religion from their upbringing. Somehow they got the message that in order to be part of that big, successful, materialistic picture you have to maintain a certain status quo concerning moral, ethical and spiritual issues. It isn’t your heart. No, you wouldn’t want that, because that’s that flaky stuff. It’s really hard to have all that you’re supposed to have if this religious thing is so in your heart that it is your heart, that it speaks to you every minute, that all of your decisions are based on what you know to be true spiritually. There’s not much chance that you’re going to be the big accumulator your parents hoped you would be if you go like that. So religion is tamed. It becomes insipid. It becomes a thing that we do as part of the whole picture of who we are, but it does not really nourish us in the way that we want it to. And we end up blaming the religion or the minister or the teacher or the prayers or something. In America, our religious spiritual picture is not empowered. It is not deepened – not in the way that would set us on fire. I don’t mean this in a fanatical way. I mean this in a way where we are never very far from what feels like spiritual truth, from what we know to be good, from what we know to be deep and meaningful. It is very difficult for us in this culture to maintain that kind of spirituality.

Copyright © 1996 Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved

Guide Your Life With Right Though Part 1: Full Length Video Teaching

The following is a full length video teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered at Kunzang Palyul Choling:

Right thought is part of the 8-fold Path first taught by the Buddha as he described the method for exiting suffering. Jetsunma explores the concept of right thought and how i weaves with your karma to affect your experiences now and in the future.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo All Rights Reserved

Liberate Your Mind

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love series

There are many Dharma practitioners who practice for many years, go on retreat, and even take ordination. Then at some point, some karmic switch flips in their minds and suddenly they’re finished with Dharma! They don’t want to do Dharma anymore. They’re on to something else. We may think that’s strange, but it has happened, especially to Westerners. It’s not uncommon for a Westerner to practice Dharma sincerely and then flip tracks, and go back into a very ordinary kind of life. That need not happen to you. But it could. You should face that possibility.

The antidote for that event is to cultivate compassion in your mind every day. If you move along the path of Buddhadharma and become overworked by it, thinking, “I just can’t practice that many hours a day. I cannot do this activity that propagates the Dharma anymore. It’s just too much.” If you become dry inside, if you think you just can’t go on, there’s only one way that that could happen to you. You have forgotten the suffering of others.

You must cultivate the memory that even in this visible world where beings can be seen, there is suffering that you cannot comprehend. You must think that there are children being abused everywhere, that there is starvation and poverty. You must think about the terrible diseases that afflict the body, speech and mind. You must think about the horrible things that come along with suffering, and the depth of suffering that exists, even in the realms that you can witness. If you think about that everyday, more about that than you do about yourself, you will not fall off the path of Dharma. When you become weak, when you waiver, that is when you forget. That is when you think the path is all about you. It’s when you forget that you are practicing for their sake, and that you are practicing also to liberate your mind so that you can be of benefit to others.

A non-Buddhist practitioner might say, “I’ve got another idea. Why don’t I do what I know how to do best. I’ll go out and make some money, and then I’ll feed everybody. I can do that.”

I’ll tell you a story about when I went to India. In our innocence, we thought, “Let’s go see Bombay; this is really going to be great.” So we got in a taxi and we went through the streets of Bombay thinking that we were going to see the India on the postcards. What I saw were streets so filled with sickness – leprosy, deformity, unbelievable poverty – that I couldn’t see anything else. I know there were beautiful buildings. I know there was beautiful scenery, but I couldn’t see those things.

Every time the taxi stopped, people with only part of a limb and open sores of leprosy would stick their arms in the car and beg. Mothers would hold up their babies that they had done something to, saying, “Help us, help us.” So I started passing out dollar bills to everyone. I soon realized I was in deep trouble as I only had a limited amount of money, but that didn’t stop me.

I was traumatized by this. I was crying to the depth of my heart, because I had known that suffering existed, but I was used to my brand of suffering. I had never seen anything like this. I continued to pass out dollar bills, and finally the taxi driver stopped. He turned around and said, “Lady, don’t do this anymore. What is one dollar going to do for these people? Maybe they’ll eat today. What will you do for them tomorrow? And if you give out one dollar to everyone you see, there are so many people like them in India, you couldn’t help them all.” His saying that shocked me; he was right. Even if I could manage to become wealthy, I couldn’t feed the world. And hunger is only one kind of suffering. How can you help the other kinds of suffering? This kind of ordinary compassion ultimately does no good.

Why are those people suffering in India, and why were you born here in the West where things are relatively comfortable? Why are there animals and why are there humans? Why are there other realms of existence? Why is there so much suffering in one place, and much less suffering in another place? It is because of karma. That is the reason for all of this. Yet there is a cure for negative karma, which is the kind of karma that causes suffering. Ultimately, it is the only cure that will work. That cure is the eradication of hatred, greed and ignorance from the mindstreams of sentient beings. And the root of hatred, greed and ignorance is desire.

This doesn’t mean if we see starving people we shouldn’t feed them, that we should immediately teach them the Dharma. That, of course, won’t work. We have to be skillful. If people are hungry, we feed them first, and then we teach them. But your job now is to do neither. You might not have money, and you might not have the ability to teach just yet. But you can do something. You can practice Dharma in such a way that you, yourself, become free of hatred, greed and ignorance. You can practice so that you can liberate your mind from cyclic existence for one reason and one reason only: that after liberating your mind, you can emanate in a form that will continue to benefit beings. You can liberate your mind from desire to such a degree that you have only one hope, and that hope is that you will be born again and again in a form that will bring this antidote to other suffering beings. That’s what you can do.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

Why Compassion?

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love series

I would like to talk about a subject that is of the utmost importance to everyone. The subject is compassion.

You may think, “Oh, I know all about compassion. I’ve been a Dharma practitioner for a long time. I’ve had many teachings about compassion.” Or you might think, “I’m a person with a good heart. I try not to do any harm, and I try to help people. Therefore, I know about compassion.” If we hold these ideas in our heart, we have already lost precious opportunities, and will continue to lose more, because the cultivation of compassion in the heart and mind is an ongoing process.

Even if you come into this world with a compassionate ideal you must still cultivate the idea of compassion as though it were the first time you ever thought of it. Due to intense spiritual practice in the past, you may have been born into this lifetime with the idea that you want to be of benefit to sentient beings. Yet still you must cultivate the idea of compassion everyday, as though it were a delicate orchid that could die in an unnatural environment. Until we are supremely enlightened, we have obscurations of our mind that will fight against the idea of compassion.

There is no one on this earth, unless they are supremely realized, who has the purified mind of compassion. If you have been meditating for many years, and think compassion is a baby subject and you’re far beyond that, or if you think because you’ve practiced for a long time, compassion is just one of the beginner studies, and now you’d like to get on to the mystical or the “higher” Dzogchen teachings, then I think you’re making a mistake. I hope that you will relax your mind and come to the point where you commit to studying compassion deeply and profoundly, as though it were your mother. You should have that kind of intimate relationship with the idea of compassion. You should seek to be taught by it. You should seek to be suckled by the mind of compassion. You should seek to be nourished in that way.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

Bring the Love

From The Spiritual Path: A Compilation of Teachings by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

All Dharma, your practice, your teachers, and everything you have ever encountered that has brought you closer to enlightenment—is only one thing: a manifestation or an emanation of the enlightened, compassionate intention of the Buddha. That is why this path appears and why we are able to practice Dharma. If you wish to follow this path, abandon your drunken, compulsive need to be right, approved of, admired. You must rely on the Buddha’s great intention. And after you finally arise in the awareness of your own primordial-wisdom nature, you will of necessity appear again and again to benefit beings. For it is the nature of that state to do so. That pristine state appears in an emanation phase—a spontaneous, natural movement that we may call love.

Who stops the love? You do. Every moment you believe that you are inherently real, you stop loving. Every moment you focus on your “self” and its needs, you stop loving. As your churning desire compulsively creates a deluge of thoughts, you stop loving. As long as you hold on to a “self” and the idea of its eternal existence, you will never be anything but a cheap imitation of the supremely awakened mind. I asked a wonderful yogini in Nepal, “What would you say to women in America who are practicing?” She said, “Well, this applies to everyone, but especially to women. Have courage.” Your practice is meaningless—it amounts to nothing—unless you have courage. You must be strong. You must not let anything stop you. With that fearlessness, you can break through the lethargy in your life; you can break through the barriers that keep you from practicing sincerely; you can even break through the old ideas that keep you mired in garbage. You can understand that by believing in a surviving, eternal ego, you are following a fool off a cliff.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

Western Baggage and Eastern Philosophy

From The Spiritual Path: A Compilation of Teachings by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

As human beings, we avoid looking deeply at our ingrained habits and beliefs. We avoid testing them for the qualities needed to develop properly on the Vajrayana path. It’s easier to “go with the flow.” We dislike challenging ourselves. Most of all, we dislike change. We are somehow more comfortable with remnants of our old beliefs, translated into Dharma terminology.

Eastern philosophy is difficult for Westerners to understand. There are so many major differences, including the basic premise and the value system. Though the various motivations for practice set forth by the Buddha are universally true, people tend to select what resonates most with what they learned while growing up. Your culture strongly influences your reasons for practicing Dharma—and how you under-stand it. Those whose needs are generally satisfied react very differently from people who have seen war, suffering, and famine. The latter tend to hang on to Dharma for dear life. But many Dharma-practicing Westerners complacently think: “If I can just get another precious human rebirth, I’ll be okay.”

Not so for those who have seen intense suffering. They are apt to think: “I want out. I want my mind to be free of the causes of suffering. I am sick of revolving helplessly on this wheel. I’m tired of watching my loved ones go hungry and die young.” When you have seen war, you know that death could be just a moment away. But we Westerners rely on medical marvels. We have faith that if someone can just get us to the hospital in time, we will be saved.

The great blessing here in the United States is that many people have a strong karmic relationship with compassion. Thus, I talk more about compassion than about suffering. But it may not be enough to practice Dharma because you feel a sense of mission and purpose—however pure your intention might be. That is not the same as hanging on to Dharma for dear life. If you have not understood in the depths of your being how impermanent this life is, if you have not really understood the terrible prospect of revolving endlessly in cyclic existence—you tend to be much more casual in your attitude toward practice. You may not challenge yourself to do your best.

Westerners need a constant shot of inspiration. We seek it out. We eat it like candy, and we love it! But just like candy, it soon lets us down. And even if we practice with the intention to help sentient beings, there is still a catch: our practice gives us a sense of identity. Right now, your sense of identity determines why you live, what you do, what is important to you. But it also makes you a traveler who is standing still. We can move very fast in our practice and yet remain quite stiff inside. If we practice because we want to be a good person who helps others, we become comfortable with that identity. We do not feel the urgency of someone living with the constant threat of being bombed—or someone who has known hopeless hunger.

We may adopt some new ideas, but our beliefs are basically unchanged. And so is our predicament. We still believe that we will exist as we are forever, if not in the same body, then with the same consciousness. We hope to attain the goal of realization as ourselves. We believe we can keep ourselves intact, and then, we will somehow appear in a celestial form in order to benefit beings. As to what we will actually do, we vaguely envision bringing love and light to the world, the bounty of our great wisdom. And to do that, we will continue to exist in some way that is recognizable to us.

We have now come to a delicate but crucial distinction, and we must tread carefully. We pray to retain awareness throughout the process of death—so that during the bardo transference we can achieve realization or, at least, rebirth in a most fortunate way. We also want to come back in an emanation form in order to benefit beings. However, we may not yet have really challenged our ideas of foreverness and sameness. That is, we haven’t given up on ego, on surviving. This is a product of our culture. Christians aspire to survive death and go to heaven. A Buddhist, however, hopes to remain awake and not faint during the time of transference in the bardo state, but understands that what remains is not the self or the ego: it is awareness itself, the pure, essential mind-nature, unobscured, un-hindered by dirty winds and channels. It is not the natural state of you, the person you are right now. If you are hoping that this “you” will remain intact, you have a different religion programmed into your brain. The correct goal is not to survive in an eternalistic way, reaching a heaven-like Dewachen and then returning as a Buddhist angel to help people.

When you pray for others, do you wish for all sentient beings to know love and light? As Buddhists, we can no longer have this as our prayer. Why? When you do that, you are wishing for sentient beings to remain intact forever, revolving in a state of impermanence. This is very different from praying that the causes for suffering will be erased from their minds, that they will realize the primordial-wisdom state.

What should you as a Buddhist hope for? That when you enter into the bardo, or into your prayers, or even into the next moment, you will instantly come to know the emptiness of all phenomena, the emptiness of self-nature. Self-nature is like a puffball. You should pray to see it for what it is: poof! Just like that. You should pray with all your heart to realize the primordial, natural, pure view—the Nature which is free of all concepts, all mind-chatter. That Nature miraculously survives beneath all the garbage we pile on top of it. That Nature is pure, all pervasive, with neither beginning nor end. When you attain that view, form and formless are seen to be the same, and self is only luminosity.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo