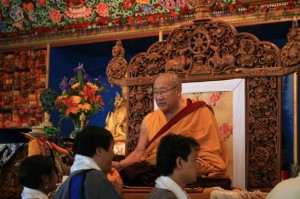

An excerpt from a teaching called How Buddhism Differs from Other Religions by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

When we study Buddhism, the first thing we come to understand is the equality of all that lives. This is a direct teaching from none other than Shakyamuni Buddha himself. He taught that all beings are essentially equal in their nature and that they all have the same exact desires that we have. We want to be happy. We strive for happiness in our own way everyday. We go here and go there to be happy. We rest to be happy. We wake up to be happy. We have our weekends to be happy. We hope the weekdays will be happy. It’s something that’s a theme in us and whether we consciously realize that we are striving for happiness or not, it is an underlying fuel that runs the machine. And when we are not happy, we are filled with desire. And when we are not happy, we are suffering.

The Buddha taught us that each and every sentient being – humans, animals, and even nonphysical beings mainly wish to be happy in the simple way that we do. I watch MSNBC news sometimes, and I watch Chris Matthews and Keith Oberman. And Chris Matthews always says in one of his commercials, “This is something uniquely American. This is something that really shows us who we are.” We are Americans, because in America there is the hope that this day is going to be the best day. And that this is going to be our favorite day, and that we are going to be really happy today. And so we wake up in America with that hope because we have the freedom to gain that happiness. We’re not oppressed or starving or homeless or something where there is no real potential for true happiness, comfort, or ease. I disagree with Chris Matthews even though I am a fan. I don’t think that only in America do we wake up with that thought. Maybe in America it seems more attainable. But the truth of the matter is, no matter where we are, what diseases we suffer from, what poverty or hunger or disability we endure, or what oppression or warlike conditions, every single person has the wish for the freedom to be happy, and wishes for happiness.

When we realize that all sentient beings are exactly the same in that way, an understanding comes up in our minds. It is a sense of the equality of all that lives. Perhaps it is a sense of budding compassion or understanding. That’s the goal anyway.

So, how does that work? Sometimes we hear about really terrible situations, and really terrible people, such as a serial killer who has murdered like Jeffrey Dahmer. Have you ever heard about him? He was a serial killer that used to cannibalize people, and live with their dead bodies, and stuff like that. Now, of course our understanding of that is that the man was extremely sick. We can understand that, but do we understand that as strange and abhorrent and bizarre, and as ghastly his behavior was, he was striving to be happy? But the confusion, the delusion in his mind was so thick, that in order to be happy, he had to completely dominate another life form. Yet underlying that, even while killing, maiming and torturing people, he was striving to be happy. That’s a bizarre thought, but it helps us to understand a little bit about the nature of suffering sentient beings.

Then we think about animals. For those of you that don’t know, I just adore animals. I feel very close to them, and I have a bunch. They are my family. Animals suffer too, and I have come to understand through my own experience, not just from the teachings, that animals also strive every day to be happy. I see my dogs move from a hot place to a cool place, from a cool place to a warm place, and it’s about wanting to feel comfortable, to be happy. Whenever you buy them a new toy or a new treat, they are gung-ho on it because they want to be happy. I’ve seen for myself that desire for happiness in humans and in animals. And so I absolutely and totally understand that what the Buddha has said is true. While we are striving to be happy, we have absolutely no understanding as to how to go about it. And therein lies the rub, as they say. Therein lies the problem.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

![284564_happiness-face[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/284564_happiness-face1.gif)