An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo on October 18, 1995

What would it be like for you if Guru Rinpoche himself, appearing in a way that you could understand, were to actually walk through every day with you? In your mind, in your heart, seeing what’s in there? Walk through all your efforts, and watch you when you turn away and say, AO.K. that’s enough of that. I’m going to go and do what I want to do. Enough of that high thinking. Let me feel the way that I naturally feel, the hell with all of you. You know, that kind of thing?

If we actually had the eyes of the Guru, if they could be felt watching us, you know what you would feel like if you had seen that happen. If you had felt that even for one day. There would never be an end to your grief. There would never be an end to the sorrow that you would feel knowing that in the face of the Guru you had made such a stinking offering.

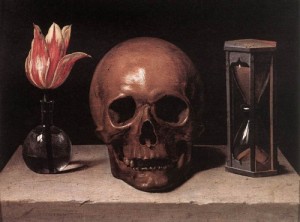

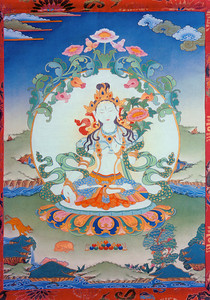

We remain content with our self-cherishing, content with our pride, content with our ego and our hatred and our bigotry and our bad qualities. We remain content with these while the eyes of the Guru watch. Because there is no moment that you exist, that you can have a thought, that you are alive in samsara that the eyes of the Guru are not watching. And I don’t mean this like you should think of yourself as a little kid thinking, “Oh no, Mommy’s watching.” It’s not like that. The Guru doesn’t get mad at you. It isn’t an approval thing. It isn’t like your mother or your father. It’s that these eyes are like a radiant connection through which we can see directly the primordial nature, which is free of any kind of contrivance and separation and ugliness and superficiality and any of the possibilities that make it likely that we are going to practice any kind of non-virtue. This nature is so pure that it’s like having the eyes of supreme, unnamable, unspeakable sweetness looking at us always, looking at us with love and compassion. And we are taking shit and throwing it against the wall and wiping it all over ourselves: scratching and burping and farting and hitting and killing and carrying on. And yet, these eyes that hold us up, watch us always, even while we, like apes in a zoo, fling shit on them.

And yet, we wonder why it is that we cannot awaken to the Buddha nature. “When is ‘it’ going to happen? When is ‘it’ going to come from ‘out there?’ How old am I going to be when ‘it’ happens to me?” — as though it were going to be visited upon you like something air-dropped; as though it were going to come to you from another city, or another state or another world. And all the time, we are turning away from those eyes, those loving, perfect pure eyes, that are actually like guiding beams of light, if you can imagine such a thing.

When we turn our face away from the Guru, we are only creating more suffering. There is no other result that can come from that, no matter what it looks like. You might say that there are extenuating circumstances. All right, name them! I’d like to see an extenuating circumstance that’s going to change what I’ve just said, because it doesn’t exist. You might say, “Well, I did my practice from this time to this time and I really tried very hard with my Guru Yoga. I worked very hard at that and I kept it mindful as much as I could and then, well, you know, you have other things to do. You have to go work, and you have to go do this, and you have to go do that.” This is the kind of thinking that we have. Basically, what we have done is, while we were in the state of devotional practice, while we were aware of being in the presence of the Guru, while we were practicing that kind of view, we have only created causes of future bliss and happiness. The moment we turned away, that act of saying, “Okay, that’s that. Now on to this” — the moment we said that, we have practiced that non-virtue which has caused us unthinkable suffering in this and every life that we have experienced up until this point. The moment we turn away from the face of the Guru and find “something else”: in that moment we have turned away from the primordial nature that is our nature, and found suffering. The moment that we go on to the next thing, is the moment that we go on to our suffering. The moment that we move away from our practice into another state, at that moment we have moved away from what causes bliss and moved into what will only bring about more suffering. This is true even if our activity is just as pure and clean as apple pie. Let’s say we ended our practice to go feed the baby. You can’t argue with that. You got to feed babies, right? Of course, you’ve got to go feed the baby, but the problem is that you had to turn away from the Guru in order to do it.

Now you haven’t actually figured all of this out yet, but now it’s time to practice so deeply that you understand that it is possible not to turn away ever. It is possible to be in that space, to be with that face and of that face, to be inseparable, to be constantly in union with that which is union itself, to be inseparable with the Guru. This is the goal!

Why wouldn’t it be the goal? Is it samsara that you wish to be inseparable from? Is it suffering? Is it non-virtue? Do you like to turn away? Maybe you like the result, the suffering that comes after! Of course, now that I say it this way, it seems ridiculous! Of course, you don’t want that! Yet, in our practice, in our lives, what do we do? We offer the five cups of poison. This is our standard offering, every day. And then we read the text and the text says if we could just offer one butter lamp, we would remain in unmovable samadhi. And we wonder, “I’ve offered lots of butter lamps! What is the hold up? What’s the problem?” I’ll tell you what the problem is. It’s those five other cups that you offer so much more of than that butter lamp.

Maybe the butter lamp needs to be understood as a symbol, not only as a literal butter lamp on an altar, but like a light in the window, a constant reminder. When you know that a loved one is nearby and you’re trying to create the connection whereby the loved one would be guided home. In this case, we’re trying to create the connection. You would keep a lamp in the window, wouldn’t you? Keep a light on? Maybe that’s what we need to do. Maybe the butter lamp we need to offer, the one that brings us to immovable samadhi is the light that never extinguishes: the light of recognition.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo