The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Marrying a Spiritual Life with Western Culture”

As many of you know, I like to climb the same mountain that you like to climb—the mountain of wisdom or understanding—so that we can get to the top and really have the full vista of understanding. I find it’s best to climb the mountain, not in a linear way, but in a way that opens up to us true meaning on a conceptual level. It’s a good thing to climb that mountain from every possible angle you can think of because on each side there will be a different experience of going up the mountain. One can truly understand the mountain by moving in those various ways as opposed to having only one narrow means of approach.

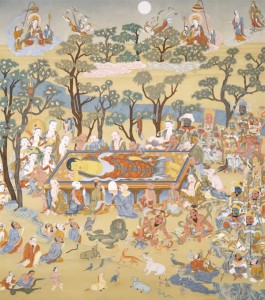

In order to broaden and to deepen, then, one has to have the intention to really know and understand more deeply, so that Dharma will be real and focused and meaningful and will carry weight in one’s life. That’s what I’d like to talk about today. In order to do so, I’d like to talk about where we’re coming from and how our culture is different from a culture in which the Buddha naturally appeared and naturally emanated and naturally gave rise to certain teachings. The Buddha did not appear in Missouri—not in the way we understand. Although in truth the Buddha is everywhere in Missouri, the historical Buddha did not appear in Missouri or Indiana or Brooklyn, not in the same way. The original teachings, the path of Dharma that we practice, were brought to us by Lord Buddha himself.

The Dharma began in India in a culture that is very different from ours. It’s where Lord Buddha appeared. Even if it is not the most potent religion in India now, it still has had some effect on shaping and forming that culture. Here in America there are religious factors that have shaped our culture, but they are different.

So I would like to examine some of the ways in which the cultures are different, just briefly enough to have a certain idea that we can examine for ourselves. The best thing to do is to look at these cultures today, with just an idea of where they came from and how they progressed. Culture in America today is materialistically oriented. We are a culture of attainers. We accumulate things. We are given a definition of success that is handed down from generation to generation and, oddly enough, it has more to do with substance than it has to do with spirit, more to do with material gain or loss than it ever has to do with joy. Joy—what a concept!

When we are coming up, we are prepared and schooled to accomplish things that have to do with getting stuff—even if we study to become something that seems to be non-materialistically oriented, such as, for instance, a social worker. You would think that a social worker would be looking at our culture with different eyes. You would think that a social worker would be asking, “Well, what are these social factors? How can we organize them into something that is meaningful and deep for us? How can we express within our culture the gamut of human expressions? How can we integrate it? How can we make it work for us? How can we discard those things that do not work for society?” Yes, that is some of the training of a social worker. But why does somebody become a social worker? And how do we approach that kind of thing? Well, we always think about how the job market is doing: “When I get out of school after I learn all of this, will I really be able to get a job?” We think of ourselves as having an office, and we think of ourselves as having that little square on the office door that says you are somebody. Then we think about whether that would be a really profitable occupation. So even if we were to approach something that could, by its nature, be fundamentally non-materialistic, we approach it from a materialistic point of view.

That’s one thing that is interesting and unique about our culture. It is so all-pervasive that it’s invisible, and you don’t really notice it until you go to other places. If you really want to learn something about your culture, leave it and come back. If mainstream America does not have that kind of experience, they cannot really see very well what the factors are. It’s more difficult. So to leave one’s culture and have another taste or another experience gives one a sense of comparison.

We approach everything in a collecting or accumulating way, in a materialistic way. We measure success by material substance. Nobody’s parents tried to raise a great mystic because you wouldn’t do that to your kid in our society. You see what I’m saying? You want to prevent your kid from the dark night of the soul. You want to prevent your kid from the ambiguous, vague, cloudy, uncharted waters of mysticism. You want your kid to be on the straight and narrow. They know where to get a loaf of bread. They know how to put some butter on it. They know how to eat it. They know how to feed it to their kids. They know how to buy a car—that kind of thing. You want your kid to be prepared for that. You do not raise a mystic. A mystic is something you have to contend with in our society. It is an avocation that is fraught with suffering.

Now why is that? Well, partially because a mystic goes into a very deep sense of connection. In order to do that, the mystic has to plow through issues or plow through whatever it is that one plows through. The other reason why being a mystic is so darn painful is because no one has any respect for that kind of thing. A mystic in our society probably is a dreamer or a ne’er-do-well who can’t dress, who has no sense of self whatsoever, is socially inappropriate, can’t figure out how to catch a cab. Or maybe a mystic is someone who is depressed, possibly should be on Prozac. These are the kind of things that we associate with a mystic’s life and that is why nobody has ever been encouraged to be like that. The idea of really profound, deep mysticism scares the patooties out of us.

But in another culture where that kind of ideal is held up as being something pure, something wonderful, something significant, one’s experience regarding mysticism is entirely different. There is a dignity and nobility about it. There is a sense that this is a worthwhile occupation. There is definitely less fear of having the freedom to utilize one’s life as a vehicle for true deep mysticism and spirituality. One of the reasons why it’s more comfortable and easier to get connected to it is because one isn’t socially ostracized.

Now the great thing about being a mystic in America is that, once you get to the point where you’re really good at it and somebody finds you and you can market it—maybe write a book or two, maybe sell something that you’ve given rise to—then you can be a success. Mystics in our society can also be successful after they’re dead. I really don’t know why. If any of you know why, tell me. But while we’re alive, we don’t have too much hope.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved