The following is respectfully quoted from “Reborn in the West” by Vicki Mackenzie:

I spent a couple of days at KPC admiring the grounds and meeting some of Jetsunma’s followers. One of them was Wib Middleton, a friendly, open man who was one of Jetsunma’s earliest students and is now the chief administrator. I asked him for his impressions of this first female Western tulku as she ventured out on her mission.

‘When we met her it was 1981 and she and her family had moved to Washington. We were really drawn to her. We were a group of seekers, about ten of us, New Age-type people who felt there was a lot more to life and who had an innate sense of wanting to contribute to society. But we didn’t have a vehicle for that. We looked around, but a lot of the New Age stuff seemed to be so self-focused and self-centered. When we met her she had a very expanded way of talking about things. She talked about “planetary consciousness and planetary quickness” and the “vibrational zero” which was her word for emptiness. It was really amazing stuff,’ he said.

‘We went and asked her to teach us, and said said “Sure.” So we began meeting in living rooms about once a week. She started teaching us meditational practices and we’d have discussions which she would lead. Looking back, I can see that she was addressing the specific needs of people around her,’ he said.

‘Although she taught confidently, as though from an inner authority, she never made claims for herself in terms of what her abilities were,’ he continued. ‘She has never done that. In fact, she has always publicly refuted the idea that she has any special qualities at all. She was always very humble. She says things like she is not a very good teacher, that she has no particular abilities. Still, we could see that she had developed certain inner qualities and crossed certain lines of consciousness,” Wib said.

If Jetsunma’s spiritual life was accelerating, her material life was deteriorating quickly. Money and physical comfort were in extremely short supply. She and her family were living in a one-roomed place with crates for furniture. She had steadfastly refused all payment for her meditation classes and was working in the clothing department of a big store while her husband was trying to find a teaching job. When things got really right, Jetsunma announced that she was thinking of returning to North Carolina where her husband had the chance of a teaching position.

‘When we heard that, we went crazy,’ said Wib. ‘We thought, “This is our teacher, we need to keep her around.” The group had grown to about a dozen or more. Late one night we dashed over to her place, knocked on the door and said, “Look, here’s the deal. We’d like to start formal classes. We’ll pay. We’ll start an organization, and the organization pays you.” She replied, emphatically, that she didn’t want to be paid to teach. We said we’d worked it out so that it wasn’t like that. We’d have an organization with a board of directors and we’d take care of it. And that’s what we did. We started formal classes and an organization called the Centre for Discovery and New Life. We had a little logo and a board of directors,’ he recalled.

After that the organization grew organically. Soon there were two classes a week, then three. And all the time the teachings that Jetsunma was giving were becoming deeper and deeper.

‘Every week it would be more mind-stretching, more amazing than the week before. We would walk in and think, “There is no possible way that the information she is going to give us could get more profound”, but it was. She was teaching about the nature of mind, the void, different subtle bodies. At that stage we were between Western metaphysical language and Eastern concepts. We certainly weren’t calling ourselves Buddhists.’

The teachings continued pouring forth out of Jetsunma–week after week. Little did the group know it then, but they were all being prepared for what was to follow. “When it happened, they didn’t notice it at all.”

‘One of our friends introduced us to a Tibetan called Kunzang Lama from a monastery in south India,’ continued Wib. ‘He came to our centre on a rainy night with a lot of carpets he was trying to sell to raise money for the monastery. He also had a book of pictures of small Tibetan kids–mostly young monks who needed clothing, books and food. At the meeting we decided to take them on as a project. None of us knew anything about Tibet and we knew very little about Buddhism. Our knowledge was restricted to Vietnamese monks burning themselves–and there was some confusion with the Hare Krishna movement! It was the typical American response to somebody else’s culture and religion,’ he said, laughing.

Entranced by the pictures of the little monks, they realized there was an excellent opportunity to put Jetsunma’s teachings into practice. ‘Right from the beginning she had emphasized compassion, seeing suffering and doing something about it. She said that suffering came about because thought of ourselves as “separate”. She talked about “union consciousness”–recognizing that there’s one operating principle–and that the one way to understand our own and everybody else’s nature was through love and kindness. She talked a lot about “stewardship” and “caretakership” of the earth and all the creatures on it.’

Within two or three weeks of the carpet-seller’s visit they had managed to sponsor seventy-five children back in south India, and a rewarding correspondence followed. They learned what the little monks were doing and discovered it wasn’t so different from what they were doing in Washington. They also learned that the abbot of the monastery was called His Holiness Penor Rinpoche, who was the head and 11th throneholder of the Palyul lineage of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism.”

The tale fast-forwards a year to when the group received a letter from the carpet-seller saying that Penor Rinpoche was making his first-ever teaching tour of the United States. He wanted to visit Washington to meet and thank the people who had generously sponsored so many of his young monks.

The group was delighted, but had no notion of who or what Penor Rinpoche was nor how to treat him. By this time Jetsunma had moved to a bigger house because they could no longer fit into her living room, but she was still doing everything herself, including all the cleaning, setting out chairs, organizing the coffee and snacks, and of course looking after her family.

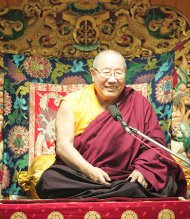

Penor Rinpoche arrived in spring 1985. When the group went to Washington Airport to meet him they found a large crowd of Chinese students already waiting to greet their guru. Unknown to the members of the Centre for Discovery and New Life, Penor Rinpoche was an extremely eminent lama with several established centres in Asia. Later they learned that back in Tibet he had been responsible for a hundred thousand monks and nuns situated in over a thousand monasteries. Like most of the great Tibetan lamas he had left his homeland in 1959 after the Chinese invasion. Starting with three hundred followers, he arrived in southern India fourteen months later with only 26: the rest had died on the perilous journey. Undeterred, he took the five acres of land and the elephant that the Indian government offered and, against what seemed insurmountable odds, proceeded to build a monastery that could hold five hundred. When Jetsunma and Wib met him his monastery was crammed to overflowing with 650 monks, many of whom had fled from the continuing persecution in Tibetn.

“Penor Rinpoche had a burning life.” Since he was young he had prayed to meet, in this lifetime, the reincarnation of Genyenma Ahkön Lhamo, the female Tibetan yogini who with her brother had founded his lineage, the Palyul sect, back in 1665. Penor Rinpoche was sure she was living on this earth somewhere. He had already met Ahkön Lhamo’s brother, a Tibetan who was also teaching in America in Ashland, Oregon. But he knew female reincarnates were immeasurably harder to track down. Tibetan yoginis, although reaching the same exalted peaks of consciousness as their male counterparts, were generally free spirits who did their meditations alone in caves. There was no system set up for finding them.

None of this was known to the small group of Americans who turned out to meet Penor Rinpoche’s plane on that spring day in 1985. What followed next was a scene befitting a Hollywood movie. Jetsunma described it to me in detail.

‘We arrived at the airport and there was this huge group of Chinese people who had got wind that he was coming and had arrived with a limousine. They knew who he was. We didn’t have a clue. They were all grouped around something or someone I couldn’t see, clicking their cameras and carrying on. Now Penor Rinpoche is short, about five foot three inches, and fat. I tower over him. I thought, “Well, I guess he’s in there somewhere, but what’s happening?” Somehow the sea of Chinese people parted, I saw him, and burst into tears!

‘Now I’m not the sort of person who usually does this kind of thing, you understand. I’m a hard-headed lady. I’m from Brooklyn, for heaven’s sake!’ she joked. ‘But I just could not pull myself together. I felt like such a ninny. I cried and cried, I just looked at him and thought, “That’s my heart…That’s my mind…That’s everything.” ‘ Her voice was soft. “How do you feel when you have just seen everything? I just knew that was it. That was what I’d been looking for my whole life. And the tears poured down my face.’

I asked her precisely what that meant.

‘Padmasambhava, the founder of Buddhism in Tibet, actually said, and I’ll paraphrase “I will reappear as your root teacher, the one with whom you have such a relationship that you understand the nature of your own mind. When you meet your teacher you will in some way see your own face, and it will be the face that turns around and moves you. It is the beginning of your awakening.” ‘