In Tibetan Buddhism the idea of compassion is talked about by using the idea of “Bodhicitta.” Bodhicitta actually means compassion, but for Westerners, the idea of compassion is often that the “haves” give to the “have-nots.” There is a sense of one person having or being in a position to give, and another one being needy. In Buddhism it is different. When one displays Bodhicitta, one understands that all sentient beings are suffering. One looks at cyclic existence and sees that it is impermanent; that all sentient beings, no matter how happy they are, temporarily, ultimately lose that happiness by experiencing old age, sickness, and death; that in the six realms of cyclic existence, there are many different forms of suffering due to impermanence and the mind of duality.

If you have no awareness of the impermanence of your situation, then you have no awareness of the fact that even though you may be happy at the moment, you are likely to suffer at some point in your life. If you tend to avoid that knowledge, you really cannot accomplish stability in your path because the motivation isn’t right. When you are suffering and you realize that you are suffering, your experience is intensified in such a way that you know that enlightenment is important. You know that this suffering that is happening to you is not good. Even if you are experiencing some temporary happiness like watching TV or feeling great when you’ve accomplished something, you notice that you feel not so great when that temporary satisfaction is absent.

According to the Buddha’s teaching, compassion and the determined cultivation of Bodhicitta is absolutely necessary in stabilizing and deepening one’s experience in meditation. Why is that so? First of all, we should look at the teaching that is called the Four Immeasurables.

The Four Immeasurables are loving kindness, compassion, joy, and boundless equanimity. Of these, the most foundational is boundless equanimity. This means the realization that all things are essentially equal. You learn to treasure your most loved one the same as those that you don’t know, including your worst enemy. How is this possible? If you look at why you care for your loved one more than you love your enemy or someone that you’ve never met, you can understand that the motivation for loving one more than another is desire. The desire that is felt here is the desire for approval, the desire for being recognized as an entity, the desire for the continuation of one’s awareness of self as being inherently real and stable. Believing in self- nature needs to continue once it is assumed, otherwise one will feel chaos or as though things are falling apart. Desire is inherent in all of this. There is another thing that you can learn from realizing the difference you feel between the friend and the enemy, and that is the belief in the separation of self and other.

Buddha teaches us that we are actually empty of self-nature. This means that although we exist in a primordial wisdom state, what we experience when we experience self-nature as inherently real, is actually a series of conceptualizations that are contrived. They are inconsistent with the pure primordial natural state which is free of all contrivance.

Boundless equanimity is the opposite of this self/other contrivance because it is the realization of the loved one and the hated one as essentially equal. To realize this, one must rid the mind of attraction and repulsion, which according to the Buddha are the very causes of suffering. They are the children of desire; they actually begin the cycle of karmic cause and effect, and they occur every time you have a thought. If there is attraction and repulsion, there is always wanting or not wanting, there is always grasping or pushing away. When attraction arises, to the same degree repulsion will also occur because the ordinary mind exists in a state of duality. If you do not experience it at that very moment it will be experienced at some future time, perhaps next year or next lifetime. Once a cause and effect relationship is set up it always realizes itself.

Equanimity becomes necessary, then, in order to have a profound and continuously stable experience in one’s meditation or practice, not floating on the ups and downs of attraction and repulsion. Through equanimity one understands the equality of all phenomena. The way that the Buddha teaches us to establish equanimity in the mind is to realize true nature, which is the underlying reality of all phenomena, including self-nature. The Buddha teaches us that the primordial wisdom state, or the ground from which phenomena spontaneously arise is clear — it has the quality of innate wakefulness. Yet the moment that you describe it you lose it, because to wrap concepts around it makes it a contrived, unnatural experience. Realizing the natural state comes through realizing equanimity, through learning how that natural state might appear or how it might be viewed, how it might arise. Then by eliminating desire from the mind stream one has the potential to experience the natural state in meditation.

How do you begin to attain this pure view of equanimity? First of all you should look at yourself in the mirror and ask, “Which part is self? Where exactly is self?” Maybe you think it’s in your brain. Imagine that you can open up your head. Can you find self there? Where’s your identity? Look at every little piece under a microscope. Where is self? Then look at something else you identify with. Do you have great legs? Look at your legs, take them apart. Look at the bones, the muscle, the cellulite. Can you find self in there? Or look in your liver, or heart, or your chakras. Maybe self is in one of your chakras. You look inside, but you can’t find it. You take yourself apart and examine every single molecule under the microscope and you still haven’t found self. So you understand then that self-nature is a concept or a contrivance that is born of a certain type of consciousness which is actually an idea of separation — the separation between self and other. The whole thing is a conceptual proliferation. In examining the nature of self we understand that self-nature is inherently empty, that it doesn’t exist the way we thought.

If self is not real, maybe I should look and see if I can find “other.” Do the same thing with all the “others” in the world. Take everybody apart, examine everything. And after you do all of this you will find that many of the things by which you have structured your life are not as they appear. From that you can begin in a courageous way to determine what true nature really is. It is through meditation that you may come to sense or understand this primordial wisdom state that is free of all conceptualizations, free of any religious idea, free of any perception of self and other yet experienced and felt as luminous and awake.

How is it then that one’s loved one and one’s enemy become essentially the same? It is because they are understood to be the same nature, the same taste. Buddha teaches that all phenomena, when understood through pure view and the stabilization of one’s mind, are the same taste. It is only desire and the attraction to other that makes loved ones and enemies seem inherently real and separate in the way we always consistently experience them.

The equality of all sentient beings allows the arising of the purely loving viewpoint found in the other three Immeasurables. One of these three is loving kindness. This kindness is not about acting kind, or adopting a set of rules to be a nice person. Instead, the Buddha’s view understands that profound nature as having one taste, realizing that all beings are equal. Their happiness has exactly the same weight as mine, exactly the same importance. From this viewpoint, one naturally develops loving kindness. There is no progress without it: This exceptional quality of desiring the happiness of all sentient beings is what the Buddha means by loving kindness.

The next of the Four Immeasurables is compassion. Here one realizes the needs of others by realizing the intense suffering of others. One realizes the fragile nature of impermanence, the needs of sentient beings and how they suffer. The wisdom, stability and intensity of determination that comes through a solid realization of these things, the compassion that arises naturally from this is the second of the Four Immeasurables.

The third is joy. Ordinarily we grow up thinking that if we just develop a good attitude and if we are positive we’re going to look happy and therefore be happy. We’re taught, “I want mine and when I get mine then I’ll be joyful because I’ll be able to act joyful then.” But the Buddha talks about joy in the well-being of others. An example would be: if I hear that you have a new car I am happy for you because you have attained even a moment of temporary happiness. I don’t make a judgment like, “Well, you’ve already got three cars, or hey, there are lots of people starving and you have a new car.”

Instead, the practice is this: the happier you are, the happier I am. If even for one moment you have achieved some level of happiness I should bless that happiness and think, “May that happiness bring you to such a point of stability and regard, may it afford you the generosity to think about others and wish for their well-being to the extent that you attain realization. May that car be the cause for your realization, may you be free of suffering in all its forms.” Or, “I wish you could have six hundred cars; I wish you could have everything that makes you happy.” It’s the joy that naturally occurs from sincerely wishing for the happiness and well-being of all sentient beings, to the extent that whatever they are capable of in terms of achieving some degree of relaxation, peace, time out from suffering, or whatever they are able to achieve that is of any benefit or any use to them at all, I am sincerely happy for them because they are the same as me and inseparable from me.

Without the Four Immeasurables and the pure view that’s implied by them, there is no enlightenment. They can be developed in the same way that you have cultivated any of the talents or abilities you have developed during your life — through determination, through taking the time to really examine the emptiness of self-nature and the emptiness of phenomena, through meditation and stabilizing the mind through pure perception of the natural primordial wisdom state, through the determination to attain compassion. It does not happen effortlessly. So it does no good to throw your hands up and say, “I can’t do this, I just can’t think that way.” Neither can anyone else.

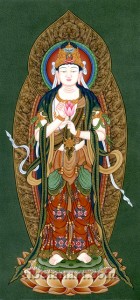

All the great Buddhas and Bodhisattvas began as sentient beings, in a state of confusion. Through the same kind of practice that you are embarking on now, they stabilized their minds and developed not only loving kindness and compassion, but the extraordinary pristine Bodhicitta that is the basis and the method for the attainment of enlightenment.

The ground from which you arise thinking that you are self and thinking that self and other are inherently real and separate, that ground is the same ground that gives rise to the most pristine compassion, the most glorious of spontaneous celestial awareness when realized with pure view. That ground is your nature, and in potential you are the same as all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Holding that in your mind, continue with determination, knowing that all things are possible.

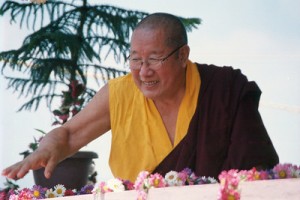

© Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

![chenrezig-1[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/chenrezig-11-272x300.jpg)