The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Commitment to the Path”

Today I would like to begin to lay the foundation by which we will practice. Even for those of us that have been practicing for some time, if we lose the foundation or if the foundation, like in the analogy of a house, becomes weak or compromised in any way, it’s not long, then, before the house will topple or the house will lean or become unstable. It’s like that with our practice. If certain fundamental thoughts are not stable in such a way as to hold up the rest of our practice and support us on the path, then eventually our path, our practice, will decay, decline in some way.

Although practice, like life itself, is often cyclic, sometimes we feel we are in a position to do more practice and other times we are in a position to do less practice. Still in all, we have to make sure that we’re able to make slow and steady progress. The reason I say slow and steady progress is because oftentimes new students will trip themselves up by trying to go too fast without the depth of understanding. It’s exactly like building your house on sand. It’s exactly like that. We want to go into the neater stuff; we want to go into the cooler stuff. We want to learn the stuff that makes us look exotic when we practice, but none of us will really be practicing in truth if we don’t have certain foundational ideas and if we don’t constantly review them over time and constantly make them part of our contemplative life.

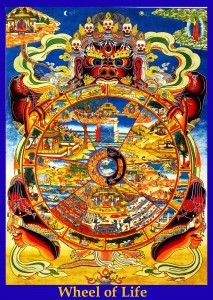

Of course those thoughts are engineered to turn the mind toward Dharma. In order to turn the mind toward Dharma, we have to have our eyes opened. We can’t be lightweights; we can’t be bliss ninnies. We just can’t say, “Oh, it’s so cool to practice Dharma. Let’s go on.” We have to understand why we are practicing Dharma, because Dharma is a path and a lifestyle and a method that one has to use throughout the course of one’s life. We have to be consistent. We have to be persistent. It can’t be the kind of faith that you have only on Sunday mornings or only on liturgical holidays. It’s a walking-through-your-life kind of thing, and it requires you to make enormous changes. Behavior and ideas that may have been acceptable before will gradually become unacceptable – not in a way that you should be filled with guilt or shame. It’s not like that. It’s more like when you really understand the Buddhadharma and you understand what samsaric existence is, and what the display of one’s nature is, it will become more natural to practice the bodhicitta and to give rise to compassion, to caring for all sentient beings.

In order to proceed effectively on this path that challenges us every moment of every day, we have to remain focused, remain mindful in ways we never thought we could or we’d ever have to. And the reason why again is that Dharma does not simply come from magical thinking. It does not come from the stars. It does not just descend upon us on some lucky day for no apparent reason. Dharma is the awareness of cause and effect relationships.

Now for me, that’s why Dharma makes so much sense. I know when I first introduced some of the ideas of Dharma to my students, they were, you might say, a little resistant. They would think things like “You mean, like path? Like you have to do something every day? Like you have to change the way you think and the way you act? I mean, couldn’t we just like get salvation?” And that’s the idea. We’ve been raised with the idea that religion is like a condiment on the plate of life. You know, something to sweeten it up with or salt it up with. A little oregano on the pasta.

But in fact, we find out that we have to learn something different. Dharma becomes our heart. Dharma becomes enthroned on the mind and heart. And the reason why is that Dharma has to accomplish something that is very breathtaking. Dharma has to accomplish something that is enormous, that seems almost inconceivable. It has to take our perception of ordinary samsaric cyclic existence, which is a state of delusion, a state of non-recognition, and it has to transform our capacity to be able to recognize our own innate nature. Yet, everything about us is geared to function in duality. Two eyes, two nostrils. All of our senses are extensions of our ego, so they always work to function in duality. So how can this thing happen? We ask ourselves, what in the world, what kind of experience, what kind of event could turn us around to where our perception could become so clear that we could be like the Buddha, awake to our primordial wisdom nature.

Well, what is it that Dharma is supposed to do, exactly, and how does it do it? The idea is to have a path on Dharma that is exacting and is a method that takes you to a to b to c to d, and also is flexible. You can go from a to d to m to t. Dharma is suitable for all sentient beings, because there is some element of Dharma that is compatible with one’s own karma. So it’s not a general here’s-the-true-label for everybody. There are teachings that the Buddha gives that are incontrovertible. They will never change. They are about the nature of samsaric existence. Yet the path is individualized. For instance, I really like to practice Guru Yoga. That’s my thing. That’s what I do. And somebody else might really like to practice Vajrakilaya. Ultimately it’s the same practice. One is a peaceful practice, one is a wrathful practice. One is based on deepening the connection with the root guru. The other is also based on that, and is also based on very actively manifesting one’s compassion.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo All Rights Reserved

![gold_road[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/gold_road1-170x300.jpg)