An Excerpt from a teaching called Our Motivation Is For Those Who Have Hopes of Us by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

I often make prayers that all of us will approach the Dharma like children. Because when we hold onto our own minds, our own self image, our intellectual prowess, we lose something. Our minds become hard. It’s especially important for long-time Dharma practitioners to approach the Dharma like children, because we get the idea that we don’t have to check on ourselves. We don’t have to examine our minds anymore. We don’t have to really look inside and see what’s happening. Then we dry up. We lose it.

If we approach the Dharma like children, we can remember the first moment we met Dharma, how it came to be important to us, how it answered our questions, and how it led us to make certain decisions. On what did we base our turning toward Dharma? What were the realizations that we had? Our answers to these basic questions are still important; they should still motivate us.

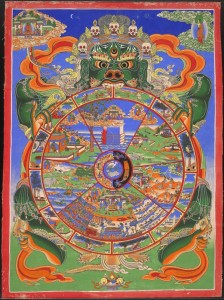

We always have mixed motivation for approaching the Dharma. What we forget is that our motivation absolutely sets the pace. It plows the ground in which the seed will be laid. Those who have the most trouble keeping their motivation pure and practicing accordingly seem to be those who have been practicing the longest. Because we’ve been practicing for a long time, we think surely we’ve got it by now. We can just jump right in and do it. We tend to forget that every day of our lives, as practitioners, we need to go back through the same process we experienced in the beginning when we tried to turn our minds completely toward the Dharma. The decisions that we made, the view that we had, the understandings that we came to, those have to be realized again and again and again. We have to examine anew every day the faults of cyclic existence. We have to examine what we’re up against.

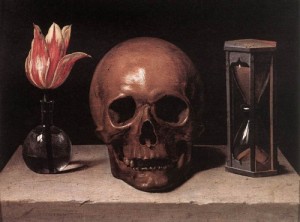

In terms of self-examination, new practitioners have an advantage. They are already looking at their motivation. They have to, because they don’t know why they should become practitioners. They don’t really understand the faults of cyclic existence. They’re going through a process that’s very raw, very new. It’s right on the surface. It’s achingly important to them. They know they’ve got to establish themselves firmly, and so they think about these matters continually. They examine cyclic existence, even having thoughts like, “Isn’t it true that everyone you know and everyone you love will die? Isn’t it true that everyone so far has died? Therefore, the life that we know is utterly impermanent. Isn’t it true that every material object that has ever made you happy has been impermanent? Isn’t it true that you cannot count on relationships — that they, too, are impermanent? Isn’t it true that you cannot count on any single condition, including your own appearance, your own health, your own psychological state?”

Even when you feel on top of it, even when you feel you’ve aced it, when you feel you’ve got the world right in the palm of your hand, you know that little pancake is surely going to flip right over! We have to think like this constantly. In the beginning we thought like that. But Dharma practitioners who are somewhat experienced, who have some teaching under their belt, who feel they have continued on the path for some time, who feel a certain degree of confidence (if not false bravado) — these Dharma practitioners forget. We don’t notice that we are not practicing from the depth of our being, that we are not practicing from our heart. “Now we’re experienced in Dharma,” we say. “We can dress like Dharma people, look like Dharma people, and we can write down Dharma words.”

But how important are these things if the mind remains hard as horn? How important are these things if the content of the mindstream remains unchanging? Do you think that wearing Dharma clothes and doing the Dharma dance can be important for you if the heart doesn’t change? Absolutely not.

Unfortunately, when we approach Dharma teachings, we tend to collect them. Like pretty things. Like treasures. And then not understanding the treasures, we put them on a shelf and we admire them and say, “Oh, I’ve got a hundred treasures, and that means something about me.” But if you are not changing to the depth of your being, and if your motivation is not right, you can have a million treasures and it won’t mean anything about you except that you have missed the point.

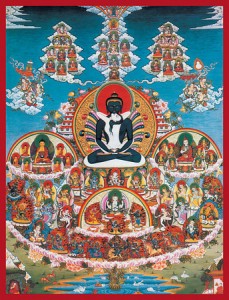

What is the motivation you should have when you approach the teachings? The lamas tell us again and again. It’s Bodhicitta. You should think, “Thus for the benefit of sentient beings, I will practice accordingly.” And only for the benefit of sentient beings, because the value of the Dharma is that it can produce the end of suffering — a promise that Lord Buddha himself made. If we practice sincerely we ourselves can be of some benefit to those that suffer. And eventually we can return in a Nirmanakaya form to urge others toward enlightenment or to directly give them the teachings.

You might as well not be a practitioner if you have not yourself looked at the world and seen the suffering there and said ENOUGH IS ENOUGH! There is too much hunger, too much war, too much suffering, too much ignorance, too much hatred, and too many people who do not understand the infallible law of cause and effect. It doesn’t matter if you are a long-time practitioner or even a monk or a nun. If Bodhicitta is not your primary motivation every time you hear a word of Dharma, read a word of Dharma, or even see an image associated with the Dharma, you have missed the point, and the blessing will not ripen in your mindstream.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo