The following is respectfully quoted from “Enlightened Courage” a commentary by Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche:

Bodhichitta is the unfailing method for attaining enlightenment. It has two aspects, relative and absolute. Relative bodhichitta is practiced using ordinary mental processes and is comparatively easy to develop. Nevertheless, the benefits that flow from it are immeasurable, for a mind in which the precious Bodhichitta has been born will never again fall into the lower realms of samsara. Finally, all the qualities of the Mahayana path, as teeming and vast as the ocean, are distilled and essentialized in Bodhichitta, the mind of enlightenment.

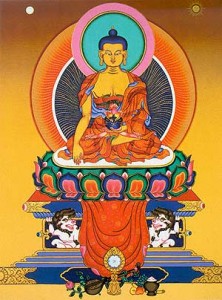

We must prepare ourselves for this practice by following the instructions in the sadhana of Chenrezig, “Take refuge in the Three Jewels and meditate on Bodhichitta. Consider that all your virtuous acts of body, speech, and mind are for the whole multitude of beings, numerous as the sky is vast.”

It is said in the teachings that “since beings are countless, the benefit of wishing them well is unlimited.” And how many beings there are! Just imagine, in one small garden there might be millions and millions of them! If we wish to establish them all in the enlightened state of Buddhahood, it is said that the benefit of such an aspiration is as vast as the number of begins is great. Therefore we should not restrict our Bodhichitta to a limited number of beings. Wherever there is space, beings exist, and all of them live in suffering. Why make distinctions between them, welcoming some as loving friends and excluding others as hostile enemies?

Throughout the stream of our lives, from time without beginning until the present, we have all been wandering in samsara, accumulating evil. When we die, where else is there for us to go but to the lower realms? But if the wish and thought occur to us that we must bring all beings to enlightened state of Buddhahood, we have generated what is known as Bodhichitta in intention. We should then pray to the teacher and the yidam deities that the practice of the precious Bodhichitta might take root in our hearts. We should recite the seven-branch prayer from the Prayer of Perfect Action, and, sitting upright, count our breaths twenty-one times without getting mixed up or missing any, and without being distracted by anything. If we are able to count our breaths concentratedly for a whole mall, discursive thoughts will diminish and the practice of relative Bodhichitta will be much easier. This is how to become a suitable vessel for meditation.

ABSOLUTE BODHICHITTA

Consider all phenomena as a dream.

If we have enemies, we tend to think of them as permanently hostile. Perhaps we have the feeling that they have been the enemies of our ancestors in the past, that they are against us now, and that they will hate our children in the future. Maybe this is what we think, but the reality is actually quite different. In fact, we do not know where or what we were in our previous existences, and so there is no certainty that the aggressive people we now have to contend with were not our parents in former lives! When we die, we have no idea where we will be reborn, and so there is no knowing that these enemies of ours might not become our mothers or fathers. At present, we might have every confidence in our parents, who are so dear to us, but when they go from this life , who is to say they will not be reborn among our enemies? Because our past and future lives are unknown to us, we have the impression that the enemies we have now are fixed in their hostility, or that our present friends will always be friendly. This only goes to show that we have never given any real thought to this question.

If we consider carefully, we might picture a situation where many people are at work on some elaborate project. At one moment, they are all friends together, feeling close, trusting and doing each other good turns. But then something happens and they become enemies, perhaps hurting or killing one other. Such things do happen, and changes like this can occur several times in the course of a single lifetime–for no other reason than that all composite things or situations are impermanent.

This precious human body, supreme instrument though it is for the attainment of enlightenment, is itself a transient phenomenon. No one knows when, or how, death will come. Bubbles form on the surface of the water, but the next instant they are gone; they do not stay. It is just the same with this precious human body we have managed to find. We take all the time in the world before engaging in practice, but who knows when this life of ours will simply cease to be? And once our precious human body is lost, our midstream, continuing its existence, will take birth perhaps among the animals, or in one of the hells or god realms where spiritual development is impossible. Even if life in a heavenly state, where all is ease and comfort, is a situation unsuitable for practice, on account of the constant dissipation and distraction that are a feature of the god’s existence.

At present, the outer universe–earth, stones, mountains, rocks, and cliffs–seem to be the perception of our senses to be permanent and stable, like the house build of reinforced concrete that we think will last for generations. In fact, there is nothing solid to it at all; it is nothing but a city of dreams.

In the past, when the Buddha was alive surrounded by multitudes of Arhats and when the teachings prospered, what buildings must their benefactors have built for them! It was all impermanent; there is nothing left to see now but an empty plain. In the same way, at the universities of Vikramashila and Nalanda, thousands of pandits spent there time instructing enormous monastic assemblies. All impermanent! Now, not even a single monk or volume of Buddha’s teachings are to be found there.

Take another example from the more recent past. Before the arrival of the Chinese Communists, how many monasteries were there in what use to be called Tibet, the Land of Snow? How many temples and monasteries were there, like those in Lhasa, at Samye and Trandruk? How many precious objects were there, representatives of the Buddha’s Body, Speech, and Mind? Now not even a statue remains. All that is left of Samye is something hardly bigger than a stupa. Everything was either looted, broken, or scattered, and all the great images were destroyed. These things have happened, and this demonstrates impermanence.

Think of all the lamas who came and lived in India, such as Gyalwa Karmapa, Lama Kalu Rinpoche, and Dudjom Rinpoche; think of all the teachings they gave and how they contributed to the preservation of the Buddha’s doctrine. All of them have passed away. We can no longer see them, and they remain only as objects of prayer and devotion. All this is because of impermanence. In the same way, we should try to think of our fathers, mothers, children and friends. When the Tibetans escaped to India, the physical conditions were too much for many of them and they died. Among my acquaintances alone, there were three or four deaths every day. That is impermanence. There is not one thing in existence that is stable and lasts.

If we have an understanding of impermanence, we will be able to practice the sacred teachings. But if we continue to think that everything will remain as it is, then we will be just like rich people still discussing their business projects on their deathbeds! Such people never talk about the next life, do they? It goes to show that an appreciation of the certainty of death has never touched their hearts. That is their mistake, their delusion.