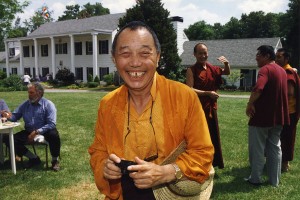

The following is an excerpt from a teaching given by Venerable Gyaltrul Rinpoche at Kunzang Palyul Choling:

Today I’m going to give an overview of the preliminary practices and how to do them because there are many little children and maybe parents would like their children to learn some Dharma. I would imagine you have that hope. Otherwise, what else is there to do for the little naughty things that they should learn? I will speak about the preliminary practices also for those of you who are new. Those of you who have heard these teachings before, it’s no problem to listen again for however much we can hear the Dharma, it should help us and improve us. So Dharma is not necessarily ever repetitive.

I’m not saying that I am learned. I am just repeating what is found in the scriptures, in the Dharma books.

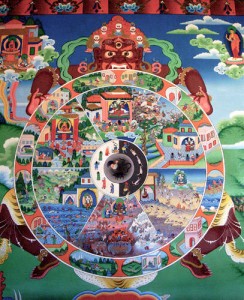

Initially it is very important to believe in the law of cause and result, which is referred to as karma, the truth of karma. For as long as we are human beings, on the path of the vehicle of humans, that is the basic view—believing in the law of cause and result. If one doesn’t believe in this, then what would that be like? That would be like thinking there is no result based on what we caused, that there is no ripening of our actions or thoughts. To believe like this is considered to be an incorrect view, a mistaken view. So again, to reiterate a mistaken view would be thinking that if I do something good, the result will not necessarily follow in harmony with that cause. If I do something bad, if I accumulate a non-virtue, the result will not be suffering—just not believing that this is how things work. So that’s considered to be incorrect understanding or a mistaken view. It’s very important to know that believing in the truth of cause and result to be infallible is the basic view of a human being.

A human being means an individual who has the capacity to think, to speak, to understand, to comprehend, to comprehend the meanings of words in a deeper sense. So, as long as we are born in this kind of body as a human, then if we believe in a religion or a spiritual pursuit, the basis is believing in the law of cause and result, which means believing that the seeds that you sow are what you will receive. This seems to be the basic view for all religions, not just Buddhism. Throughout the entire world, anyone who is following the path of righteousness, or that which is worthy of believing in, has to believe like this. If not, I can’t imagine that that would be a religious pursuit.

Disbelieving in cause and result would be like becoming a communist. A communist view is that, for the most part, this is not worth considering, although, even communists would tell us don’t steal, don’t lie. There are certain disciplines that were enforced that are also based on the notion of cause and result because they are saying if you do this, such and such negative thing will occur. So don’t do that based on that reason. In other words, the idea is that through this particular cause that result will occur. And so, that is actually cause and result, even though they claim that this is not a valid view.

I wonder what the children think this means. This means, according to your level, following the truth of what it is your parents tell you not to do. Like if your parents say don’t touch fire, the reason is because if you touch the fire, you’ll burn your finger. So that’s why parents say don’t touch fire. Because according to cause and result, touching fire means burning your finger and suffering. Or if parents tell you don’t kill bugs or if they tell you don’t steal or don’t lie or don’t drink or don’t smoke, or go to school, then if you listen to your parent’s advice, then that means that you will be responsible, good and noble. If you don’t, you will be irresponsible, ignoble and there will be problems. Likewise for adults. Keeping the rules of the government means that your life will be smooth. Keeping the rules of the Dharma as a Dharma practitioner—the words of honor and the vows—means that your practice will go well. But if there is no discipline to check in this way about the law of cause and result, following what is right and wrong carefully, then just thinking, “Well, I am just going to do things my way,” then that really is just becoming crazy, becoming silly or stupid and showing that you don’t have any qualities at all. Someone who follows rules nicely is someone who develops wonderful qualities. The inability to be able to do that really comes from inflated ego or pride, which is just great self-cherishing based on delusion. Of course, children don’t know this yet, so children need to be told and guided, but adults do know this and they should know how to guide themselves.

That is why there are always rules and guidelines in life in terms of a country, our area, our families, our school, the military, the church, the temple. Human beings always have rules and guidelines and regulations to observe. Even animals have their own rules and guidelines. That’s why we must learn what these are and follow them. In terms of Dharma practice, that means with seeing and contemplating and learning so that we can be able to identify and acknowledge mistaken directions. So rather than that, just thinking, “I am so great, I know everything, I don’t need to learn anything,” is like a mountain sheep with big horns, really not so great. Even if you are rich, even if you are a great scholar, if you have great pride in this way, you are just shaming yourself.

But please be careful. It’s not enough to just know how to play.

That’s why it is so important to study and contemplate, especially if one does not know these things. America is a very good country because in the schools children are taught how to be decent human beings. They are given many amazing opportunities, inconceivable opportunities, to learn many different things. That is not the case in other countries; these opportunities don’t exist. So we have to think about the possibilities of our environment and how fortunate we are and appreciate that and make the most of it.

According to the path of Buddhaist practice now, the subject of non-virtue involves ten specific non-virtues: three of the body, four of the speech and three of the mind. These ten are meant to be abandoned. And then the opposite of that non-virtue is meant to be engaged which becomes the virtue—the ten virtues. By abandoning and engaging, then, there are two steps and one is able to accumulate two good deeds. In terms of the first non-virtue of the body—killing—by avoiding, abandoning killing, one has accumulated the good deed of that abandonment; and then by going on to save life, one is performing or engaging in the virtue, which is the opposite of killing. So there are two, not only just one, not just only abandoning killing, although that is one stage in the virtue; then protecting and saving life is the second, which completes that. In the case of stealing, not only just abandoning stealing or taking that which is not given, but going on to express generosity, to be generous in various ways. In the case of adultery, not just only abandoning adultery, but going on to practice discipline. So these are the three non-virtues of the body. And the corresponding virtues of the speech, of course, not just only abandoning lying, but always trying to tell the truth and so on like this. Each non-virtue has its opposite, which is the virtue.

https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/2011/09/ten-virtues-and-ten-non-virtues/