![T-065[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/T-0651.jpg)

An excerpt from a teaching called Viewing the Guru: The Seven Limb Puja by Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo on October 18, 1995

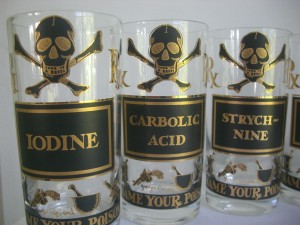

While we are constantly in the face of the Guru, we should remain constantly in the posture of understanding that we should return the favor of the Guru’s kindness. What kindness is it, I wonder, that would cause the Buddhas to appear, having emanated from the state of nirvana, in the world for the sake of sentient beings, experiencing all the conditions that are worldly and ordinary? Experiencing all those conditions, for the sake of sentient beings, rather than remain constantly in the bliss of nirvana. Amazing and wonderful, isn’t it? What kind of kindness would that take? When we think of the Bodhisattvas who remain poised on the brink of realization, emanating constantly into the world, endlessly: because how long will it take to empty samsara? These holy ones know that we are talking about what seems to sentient beings like forever. What kind of love would it take? We think about the kind of love it takes for a mother to suffer and bear her young. We think of the kind of love it takes for a mother to feed and care for her young. We think of the kind of love it takes for a mother to patiently explain, patiently teach, patiently go through what needs to be gone through. We’re talking about the quintessential mother, and this mother would patiently explain, because all the mother would care about is raising the child so that it is fully functional, fully competent, fully happy, fully blossomed in every conceivable way. Now that’s a lot of love, isn’t it? Just think what kind of love it would take for a loving parent to give, give, give in that way. Hardly any of us can imagine such a thing because the samsaric parents that we have, although their kindness is evident because we are here, many of them have not known how to love. They simply haven’t known how. And so their love was never perfect, not any of them. But we’re talking about a perfect mother. What would that be like? What kind of love would that be?

Then, if you can imagine that, which is practically unimaginable, how much more so would it take to imagine the kind of love and compassion that it takes for the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to appear in the world for the sake of sentient beings under ordinary conditions again, and again, and again uncountable times? What kind of love is that? We who give and take love like we change our underwear; we who give and take love according to what’s in it for us, we can’t even understand that. And yet we must try. We must try to understand that level of compassion. Not only do they return for our sake, but they practice for our sake. These Buddhas and Bodhisattvas have accomplished supreme realization, many under terrible conditions, going through terrible tests and trials, which is part and parcel with their coming into their own. They’ve crossed this ocean of suffering under extreme effort. Lifetime after lifetime of practice and accomplishment, and they did so for the sake of sentient beings. They literally did so for the sake of those who have need of them, who have hopes of them. And then, having accomplished that, on top of that they return again and again and again for the sake of sentient beings and would return for even one, for you. What kind of love is that? What kind of compassion is that?

We should contemplate and meditate on that, and then we should think that we must repay that kindness. In order to repay that kindness we have to think: what is the goal of the Lama? Why does the Lama appear in the world? Of course the answer is, for the sake of sentient beings; because it is unbearable that sentient beings remain suffering in the world; because the Lama cannot bear it; because it is unthinkable that sentient beings should continue to wander helplessly in samsara. It is for that reason that the Lama returns to the world, that the Lama appears in the world. Therefore, every bit of merit that we can manage to accomplish, merit that we have accomplished in the past, in the present, and even counting on the merit that we will accomplish in the future — we call that ‘the merit that we have accomplished in the three times, past, present and future’ — this we should constantly offer for the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings. We should be constantly looking for ways to accomplish merit, constantly looking for meritorious activities so that we can offer that for the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings. We should never think, “Oh, that was good. Got some!” We should never think things like that, ever, because that’s not how the Lama thinks, and we are wishing to repay the kindness of the Lama.

Dedication of merit in this case can be understood as repaying the kindness of the Lama. The Lama has given the nectar to you. You must, in turn, find a way to give the nectar to the Lama, to the same degree that the Lama has done. We’re not talking sloppy. That doesn’t mean, “Oh, the Lama has given me the nectar so I’ll practice and I’ll dedicate the merit. Period.” Doesn’t that kind of thud a little dully when it hits the floor? We are talking about going through the same extraordinary activity that the Lama has gone through in order to accomplish their practice; achieving supreme realization, and then returning for the sake of sentient beings. This you must do in order to repay the kindness of the Guru. And this is the ultimate dedication of all merit to the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings: the gathering together of extraordinary merit, the accomplishment of meritorious activity, and the returning for the sake of sentient beings, offering that merit as a gift, as a feast, just as you have been offered the feast of Dharma by the Lama.

So instead of the lovely feast that we have offered to the Lama so far: that feast of hatred, greed, ignorance, jealousy and pride, now we pay homage; we make offerings; we offer confession; we rejoice in the capacity of those who have accomplished; we request the nectar of the teachings; we beseech the Lama, the Buddhas and the Bodhisattvas to remain in the world for the sake of sentient beings; and we pay back the great kindness of the Guru by dedicating all the merit that we have ever accomplished, or will ever accomplish in the three times, for the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings. And we make the commitment here and now — not a moment from now, but right now, right this moment that we ourselves will not rest until we achieve supreme realization so that we can return for the sake of sentient beings:

“Following in the footsteps of my Guru, I will accomplish.”

This is the prayer. This is how we practice.

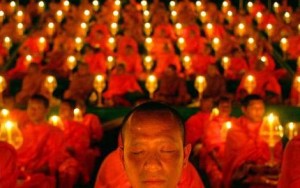

This teaching and the others from Viewing the Guru: The Seven Limb Puja (type “Viewing the Guru” into the blog search bar to find all related posts) contain pointing-out instructions that I would consider to be concentrated, important and many-layered teaching. If you really comb through it in a responsible way, extracting from it every single bit of nectar that you can, you will receive a lot more than perhaps you have even received reading it. Please read these teachings and accomplish the practice in that way and think that this is how you should be from this moment forward: in this posture, in this way, inside, this is your practice. You need not look any different at all on the outside. In fact, it would be best if you didn’t! Because then if you were, I would say that it was an act. There doesn’t have to be any words, there doesn’t have to be any show. You don’t have to walk around saying, “Oh yes, I’m doing this!” The thing should begin within you, quietly, in a deep and profound way, indicating that, at last, you have entered into the well of your own natural mind, and have begun to draw up the nectar, the nectar of the Guru.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

![brass_ring[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/brass_ring1-221x300.png)

![CHENREZIG[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/CHENREZIG1-251x300.jpg)

![T-065[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/T-0651.jpg)