An excerpt from a teaching called Perception and Karma by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo, July 19, 1989

An excerpt from a teaching called Perception and Karma by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo, July 19, 1989

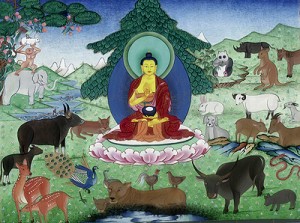

I’d like to illustrate some very basic teachings on the six realms of cyclic existence by looking at a cup of water. In the human realm, this is a cup of water and it has lemon in it. I know that it’s water because it smells like water. It tastes like water with lemon. I know what that tastes like. I can tell the difference between tastes. I know that water is good for me; I know that it will quench my thirst. The reason why I’m having this experience is because of my karma. In the animal realm, a dog would also experience that. Let’s say a dog or some kind of lion or tiger or bear would experience that as water, also. They wouldn’t know what the lemon was, they would think there was something funny in there, but they would experience it as water. They don’t taste very much. They know the water by smell. They can’t taste the difference between city water and country water. They might be able to smell a difference. But they know it to be water, and they instinctively drink it when they are thirsty. They don’t think much about whether it will do this or that for them. They don’t think about how much they need. So their experience with water is similar, but different.

In the hungry ghost realm, beings are horribly thirsty and horribly hungry, and their mouths are very, very tiny, so they’re not able to take in food. Someone from the hungry ghost realm would experience that as a cup of pus and would not be able to drink it because their experience is that it’s pus, it’s horrible and it isn’t drinkable, it isn’t water. It smells foul and is foul. It is not something you would drink. So, they do not drink and they continue to be extremely thirsty. This is my cup of water, I know that it’s not pus but in the hungry ghost realm it would be experienced as pus and they would be terribly thirsty.

Why do they experience it that way? Are they jinxed? Did some magician go to the hungry ghost realm and transform all the water? Is someone out to get them? Had they just not looked in the right places? Should they keep on checking around? Should they think positive? What would happen if they could get it down? Would it act like water? No, it would act like pus, right? Even if they could drink it, the water would act like pus to them. No matter what they do, it remains pus and they remain thirsty. That’s really disgusting, isn’t it? Why does that happen? It happens because of the karma of their mind. Their perceptual experience that they have, the construction that they abide within has that reality or that quality because it is an emanation of their mind. It is the karma of their mind. It’s as real and as solid to them as the fact that this is water to me.

What about someone from the hell realm? Depending on which hell realm it is, it would be either a cup of fire or a cup of ice. Unfortunately, it would be a cup of fire if they were in the hot realms and it would be a cup of ice if they were in the cold realms. The difficulty is that if they held their nose and said, “I really think this is probably water.” They would drink fire and be burned. It’s very real, very real to them. Why is that the case? It is the case because that is the karma of their mind.

On the other hand, if this were experienced in the god realm, it would be experienced as a cup of elixir, the nectar of long life, or the elixir of infinite power, or the nectar of infinite beauty. The gods would drink it and live a long time, anyway. Nothing is forever in the god realm. They would take it and it would be like an elixir that would put them into a state of absolute bliss for a while.

Well, I drank that water. I drink lots of water, and so far, no bliss. So it isn’t happening to me. That’s because the gods have the karma of their minds and that’s how it works out for them. Each one of these different beings that I have described arises from emptiness. They are the same as emptiness; they are inseparable from emptiness. Each cup in those different realms, no matter what was in it, arises from emptiness, it is the same as emptiness, it is inseparable from emptiness, and yet the experiences are totally different. The experiences are different due to the karma of our minds.

Everything that you have ever experienced is completely relative, completely artificially constructed and totally experiential. Everything that you have experienced is like that, and yet what do we do?

Let’s think about the poor old guy in the hungry ghost realm with a cup of pus. That’s really disgusting, isn’t it? Let’s say that he picks it up and he sees that it’s pus, and he puts it back down. Now what is the next thing he does? He sits there and he feels really miserable. He feels agonizingly miserable and thirsty. Then he thinks, “Why does this happen to me?” Then he thinks, “Everywhere I go, there’s this stuff.” He thinks, “There’s no relief.” He goes on and on and on and continues with the experience. The experience does not stop when he decides not to drink it. He continues with the experience. He reacts to the experience. The karma is that he experiences pus. He’s in the hungry ghost realm and he’s experiencing phenomena as he experiences it, which is pretty disgusting, and he’s experiencing also this great longing for nourishment and help and respite from his suffering.

Then, after he doesn’t drink it, he continues with this process of saying, “Why doesn’t anybody love me and give me something to drink? Why do I have to suffer this way?” And then goes on with, “I’m so hungry, I’m so thirsty, I’m so ugly” and so on. What I have just described is an elaboration process that branches from the original karmic occurrence. That elaboration is a very important factor and a very important thing for us to look at and understand. It is the process of exaggeration. Now, it sounds really far fetched to talk about this guy in the hungry ghost realm, but I use that example because it’s so solid, you can really understand how that might happen.

What about us? Let’s use for example the experience that we have when we lose our job. We lose our job, and it’s not the first time we’ve lost our job. The karma of that particular relationship that you had in order to have the job, ended. Maybe it just ran out because it was time. Maybe it ended because you ended it but the karma of that particular relationship ran out. What happens after you’re fired, though, is a process that continues and becomes more a part of you than the actual firing or even the job ever was. That process is the process of exaggeration and elaboration. You begin to elaborate on the process.

The first thing that happens is you begin to make an entire scenario about what really happened. What really happened has a certain flavor. You have perceived it in a certain way. You have lost your job and you have the perception that your boss was kind about it, or your boss was mean about it, or it happened in this way, it happened at midday, it happened at night, it happened in the morning, it happened when it was a good time for you, it happened when it was a bad time for you, it happened before your car payment, it happened after your car payment. You have your own kind of perception about it.

Spinning off from that, you have your determination, which is a more subtle process, about what the real story is. In other words, you’re always going to decide for yourself whether you should have been fired, whether that was righteous, whether you should be treated meanly or whether you should be treated nicely. You’re always going to decide for yourself whether things happen as they do for good reasons, and then you’re going to make up a whole story about how it should have happened. Probably you spend the next few days, weeks or months reworking the entire thing, and imagining what you might have said to your boss under different circumstances. You have your own particular belief about how things should have happened. From that you continue to elaborate and exaggerate situations, working it into the roots of your being, thinking ultimately, after you really work it down the pike, I’m a failure. “Nobody loves me. My mother didn’t love me. My father didn’t love me. I’m destined to be poor and I am deeply flawed.” You know what you do. I don’t have to tell you. You go into the entire scenario of all the different things that you feel are absolutely true. So the experience doesn’t end with the cessation of a certain job opportunity, it continues with an elaboration process and that process is as real as the actual experience. The exaggeration process usually is the one that sticks with you, longer that the experience itself, often longer than the job itself. That is the experience that sticks with you.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved

![gold_road[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/gold_road1-170x300.jpg)

![broken-chain-small[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/broken-chain-small1-300x207.jpg)