An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called Longing for the Guru

Longing for the Guru is something that each of us experiences. Each of us experiences that longing for the Guru in many different ways.

In order to be with your Teacher — however good or bad that Teacher may be — you must have spent a great deal of time making wishing prayers that you would never be separate from your Teacher. Especially if you are in a situation where you are consistently close to your Teacher and have a great deal of relatively intimate guidance, you must have spent a great deal of time longing for the Teacher. It’s the only karma that will allow this situation to exist.

As we grew up, each of us must have experienced the seeds of that longing. If we look back at our earlier lives, we may not understand that. It’s very difficult to understand how we ended up practicing Vajrayana. We certainly weren’t brought up this way. We certainly had no idea in our younger lives that we were going to be Buddhists, that’s for sure.

Yet, if we were to look deeply, we would discover that somewhere in our childhood there was a longing, which was the seed or the residue of something that we experienced in a previous incarnation. Probably when we grew up, we never heard of a Teacher. We never heard of a Guru. Because it was not consistent with our culture, and it was not sympathetic with what our culture views as proper, we may have diverted that longing into different paths. We may have felt the longing as a need to find ourselves, or we may have felt a sense of waiting to be given instructions, or to find something that we knew we would find.

Some of you might have felt you were waiting for a time in your life when an understanding would come. You might have felt a recognition that someone or something would come into your life and bring about change. You might have felt as though there was something incomplete and that completion would come later. You might have had a sense of waiting. So even while you were extremely busy in your life, there were certain things that you could have done that you didn’t, because you were waiting. Did you at some point hold back because you felt as though part of you was waiting? Maybe you even felt as though you were the ball in a roulette game, that was still going around without falling into the slot yet.

For instance, it is possible that you felt a sense of searching and perhaps went from relationship to relationship, searching for someone who would be intimate with you, searching for a fullness that you never found. It could be that you even went from a self-help group to an insight situation to a church to various kinds of situations that you thought would bring you the answer and you had no idea that it was a spiritual search. But now in retrospect, do you think that perhaps you were looking for something you didn’t find because you did not understand exactly what you were looking for? Surely, if you examine your life, you will find something of that longing in your past.

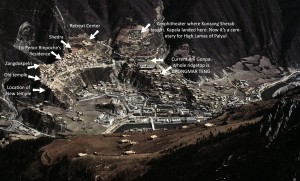

One of the great difficulties we have as both practitioners and people involved in a materialistic culture is that we have very little understanding of that longing. But in a culture that has a spiritual foundation, that recognizes the role of the Guru, or that recognizes and approves of a tendency to long for spiritual fulfillment, it is much easier to put a name and a label on that longing. For instance, in Tibet you could simply go into the monastery and know that you would find the answer there. Even if you didn’t understand which deity you were longing for, or what Guru you would find, you knew that the first thing to do was go into a monastery and with faith, the guidance would appear.

But, in our culture, in order to survive that kind of longing, you have to make believe that it’s something else. You have to pretend that it has to do with human relationships, or with prosperity, or with a certain lifestyle. You have to pretend that it has to do with intelligence, or with mental health. You have to pretend all sorts of different things in order to put the longing into some slot that our society recognizes. Because if you don’t, as you grow up, especially in the formative years, it’s crushing when you know in your heart of hearts that you are very different from others. No one else seems to have quite the same feeling that you do.

And so, because it’s so crushing, and so lonely, often, the very people that long the most are the ones that have diverted that longing into, perhaps promiscuity, or perhaps becoming almost fanatical about one idea or another. Maybe they diverted that longing into drugs or alcohol. Perhaps they made themselves into a way that they are not, such as superficial, or hard or tough or dull or even dead. They might have pretended that they had no feelings at all in order to deal with the ones that they did have.

Now, it’s true that lots of people have these same feelings and these same ways of dealing with feelings. For instance, it’s very possible that someone whose mother or father didn’t love them could become promiscuous simply for that reason. Yet, that does not preclude what I’m saying. You should listen to your life — what you did and what was underneath it. And you should come to understand that perhaps there was something a little different in your heart and in your mind, and it was always with you.

By the time you have grown and begun to find your path, you have already lost yourself somewhere. You don’t understand yourself any more. You have already done things for which you do not forgive yourself. You have already substituted something else for the longing that you felt. You have already substituted something else for your Teacher. In having done that, it is difficult to find your way home. It is difficult to reach what was originally very pure in your mind. It is difficult to rebirth what was very pure and tender inside of you. And now, you can’t just say, “Oh, I found it at last. The longing is finished. I found what I’m looking for. I found my path, but in the meantime, I’ve been promiscuous and I don’t forgive myself”, or “I’ve become tough, numb, or materialistic.”

What happens is that we see that what’s in front of us is so precious and it’s just what we’ve been waiting for. Now, instead of being able to just grab it and eat it, what we do then, is try to deal with the numbness, the hardness. the promiscuity, or the materialism. This is because we have become used to this feeling of longing. So the longing remains, and we are not able to truly be one with the path and with the Teacher.

We’ve forgotten how to satisfy ourselves. We’ve forgotten how to do anything except blame ourselves and be angry. We make lots of mistakes. We compulsively make mistakes. We do not follow the path purely and with a full heart. We have to ask ourselves if the person who says, “I’ve got to get through with my Three Roots practice today,” is the same person, who, as a child, was waiting hungrily for something. It’s not the same person. We feel differently now than we did back then and we don’t know how to get back to that original place of purity. We feel something is amiss when we think we’ve found our path because we feel angry, guilty and dirty. We feel different, impure. Then we end up approaching the Teacher, the teaching, and the path itself, in an impure way, because we believe that we are impure somehow.

Having longed for the taste of our own nature for such a long time, now when we look at the Teacher and the teaching, we see it as something altogether different. We see the Teacher as just a human being and we try to get close to that human being. And why do we do that? We do that because we spent our whole lives trying to fit that longing into an acceptable picture and now we’re still trying to do the same thing.

We are afraid to experience the depth of our longing, and instead, we try to get close to the person. We are afraid to experience the bliss of the union between the meditator, the meditating mind and the nature that is meditated on. The bliss of that union is so strong and we are afraid to experience it. So instead, we long for some kind of union with the person who is now our Teacher. It is even common to feel a strong sexual urging for our Teacher. It doesn’t matter if the Teacher is the same sex. Students can have dreams and strong sexual urgings for the Teacher. If you think of the Teacher as a mother figure, or a father figure, or an authority figure, or a therapist that you come to with your ordinary stuff, there will never be satisfaction, because that isn’t the truth. That is not the nature of the Teacher. That longing becomes a perpetuation of the suffering that we had as a child where it was not understood, where it was diverted, and where it could not be satisfied.

We misunderstand the feeling of longing. The longing is for union, not for sexual behavior. Because it is misunderstood, what generally happens is a feeling of rejection, because the Teacher does not comply with our wishes. We feel guilty and wonder what’s wrong with us. We feel a lack of acceptance of ourselves, or a lack of confidence, or a feeling that we are somehow impure in our motivation. The longing sometimes becomes so strong that we are unable to practice.

You want the Teacher to hold you and love you or you want the Teacher to be with you as a friend. You are unable to practice because you are so busy watching how your Teacher acts towards you. Does he or she smile at me? Does he or she hold my hand when I’m lonely? Does he or she notice when I’m ailing? Does he or she come after me when I’ve strayed? You’re so busy noticing that that you do not practice. The practice is the caring for you. The practice is the coming after you when you have strayed. The practice is the taking you home where you accept and awaken to your true nature. The teachings that you receive are your relationship with the Teacher. They are the fruits the Teacher brings to you. If you are longing for union with the Teacher, when the Teacher teaches you from his or her mind, and offers you the essence of what they know, that is the union, far more so than any physical friendship could ever be. There is nothing more intimate than that.

Yet, we continue to not understand. We continue to divert the longing, to not accept ourselves and to blame ourselves. We continue to create a bad relationship with our Teacher. If we understood what was happening, we would run to the teacher, run to the path, run to the experience of being on the path and of practicing in order to achieve enlightenment, with open arms and with an open heart. But instead, we are doing other things that do not accomplish the awakening that we wish.

And so, if you feel that you have become deadened to that longing, if you think that you don’t long for your Teacher or long for the Buddha, if you think that you don’t have a heartfelt longing for that awakening, then you should try to remember your childhood and the different feelings that you had. What were some of the things that you did? Were you promiscuous? Did you become involved in drugs or alcohol? Did you become very materialistic in certain ways? And if you can remember the beginning of that, was it based on longing? Was it really based on something that you could hardly remember, but remember that it was sharp and poignant?

If you can remember that time, you should become reacquainted with the purity of that urging. Cultivate that longing. Don’t cultivate it in a false or contrived way, but search for what was already there. Feel what was felt. Don’t make up a feeling. That’s important because if you do, you’ll blame yourself again. Instead, try to remember that feeling, even if it just numbs you to think that you have gone so far astray. You should not be ashamed because it was your karma to be born a culture where what you felt was not acceptable and you tried to fit-in in ways that were acceptable. Those ways did not work for you and then you shut down. You should try to go back to that original feeling and then you have to forgive yourself.

In order to be able to fully forgive yourself, you have to confess. Don’t confess, “Oh I’ve been a bad girl or I’ve been a bad boy, I’ve done this and I’ve done that.” The confession that you should make to the primordial Root Guru is, “You were everywhere and I tried to find you here.” Your true confession is your lack of understanding the nature of the Guru. Your true confession is your not understanding what you are. That’s your real confession and the real sin you committed. Yes, karma happened. But that core confession and purification can bring about the end of all the karma that arose from that, truly. It can bring about the end of all suffering that came from that point.

You should allow yourself to remember the longing that you felt and learn to live with it. In living with it and having it be the warmth in your heart, that longing will bring the proper result. So long as it is diverted, so long as you refuse to feel it, so long as you do not allow yourself to be pure and constantly cover that up with feelings of impurity, so long as that continues, the longing cannot be satisfied.

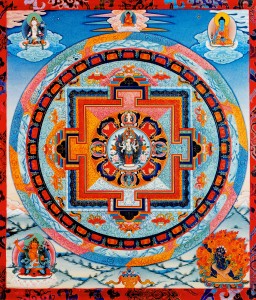

If you feel that longing purely, and if you can manage to get your ego out of the way, then that longing can be the very bread that nurtures you to continue firmly on your path. That longing can be the way that provides the actual, undeniable connection with your own Root Guru. It perfects that relationship so that you can realize the nature of the primordial Guru. You can understand that what you see in front of you is the miraculous touch of Lord Buddha. Your relationship with the Teacher, the path, the teaching, and your own practice can only be a result of the miraculous intention of the Buddha. So long as you continue to understand the teaching and the path as something external, you will never understand its nature. You will never be able to truly drink of the taste of that nature. Instead, you will continue to feel separate from the mandala.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo