Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo and her sangha welcomed a new Shakyamuni Statue to Kunzang Palyul Choling in Poolesville, Maryland yesterday.

Buddha

Limitless Kindness

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love series available on Amazon

One of the most important and central thoughts in Buddhist philosophy is the idea of compassion. The Buddha taught that we must cultivate our lives as a vehicle to be of benefit to all sentient beings. It’s good that you’re a good mother, and it’s good that you’re a good friend, but we can’t limit ourselves to a small, familiar circle. We have to go on and on increasing our compassionate activity, our influence and our determination until we attain a level of kindness or compassion that supersedes what we believe is reasonable. We can’t stop even with our nation. We can’t think that we only want to help Americans. Nor can we stop with our world. We can’t think that we only want to help humans and animals, which are the ones that we can see. We have to think, according to the Buddha, that we wish to be of benefit to all sentient beings.

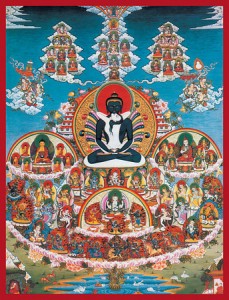

A sentient being is one who has sensory feeling or the development of that kind of discriminating consciousness. According to the Buddha’s teachings, there are six realms of cyclic existence, and there are sentient beings in all of these realms. The human realm and the animal realm are visible to us. This is living proof that at least some of the Buddha’s teaching is right. We see human beings and we see animals; therefore, we know that they exist. But according to the Buddha’s teaching, there are also non-physical beings and different kinds of beings that must be considered if we are to truly develop the mind of compassion.

Limiting ourselves to an identity such as,”I am a woman,” or “I am a man,” or “I am an American,” or “I am a Russian,” or even “I am a citizen of planet earth,” is not the way of the Buddha. Instead, we should think that on every particle we can see, and all those that we cannot see, and in every inch of space, there are millions and millions of sentient beings. And space goes on forever. If we intend to develop the mind of kindness, it must extend to all sentient beings equal to the limits of space. Space has no limits and there are limitless beings, seen and unseen. Therefore, we must extend the mind of compassion to beings far beyond those we can conceive of with our brains. That is an awesome thought. How can we really do that? We think that must be impossible. How can we be directly concerned with somebody we can’t see? How can we really care about something that might be infinitesimally small, like bacteria? Or a sentient being that may be as large as a galaxy? How can we seriously consider we must be kind to all sentient beings in that way?

When you develop the mind of compassion, you have to be careful how you develop that mind. If you examine yourself profoundly and honestly – and you have to be willing to be very honest with yourself – you may find that your goal is not really to benefit all sentient beings, but to be a kind person. There are worlds and universes of difference between these two goals. One is selfless: you truly wish to be of benefit to all sentient beings. The other is heading in the right direction, but ultimately it is not selfless because you wish that you could be a kind person. I hope that you can hear the difference between these two ideas. There are worlds of difference between them.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

I WON! A Precious Human Rebirth!

An excerpt from a teaching called Dharma and the Western Mind by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

When the Buddha speaks of the reasons why we should practice, he speaks primarily of the fact that all sentient beings are suffering and that they experience this suffering in one form or another every moment. Even when they are extremely happy, sentient beings experience the suffering that is inherent within that happiness. The happiness is impermanent and will soon be over: we have all experienced that. We have all been afraid of our really good moods because we know that they will end. And there are some times we are not willing to give ourselves over to a wonderful experience of wholeness, or happiness or love because we know that there will be a day when the mood swing will go in the opposite direction and then ‘kurplunk’ – there we are again. So we have difficulty in relating to that kind of concept. We also have difficulty in relating to the fact that we should be motivated to practice because the conditions of cyclic existence are unpredictable. There is something about our culture that is pretty regimented.

Here in this country we know that if we are born, probably we will get to eat. We know that there are people who are hungry but we don’t get to see them very often. Most of the public knows that it is going to eat. They may eat on welfare or caviar and pâté but they will eat. We know pretty much that if we are sick, there is a place that we can go to get help. Even if we have to get free help; still we can get help. It’s true there are exceptions but I am thinking of the greater population. The greater population has a certain regimentation that it is accustomed to things upon which it can rely. We really don’t see too many people dying very young. Proportionally there is less infant death and death by disease in young people than elsewhere. We see it but somehow it is not a major part of the fabric of our lives and so we find a way to work around that. We think that it is not a good reason to practice because the chances are good that we will scoot through it okay and even though we really do know that we might not be okay. It could be that we could die young or experience some suffering; still we think that the chances are that we will be okay.

We have also been shielded from some of the more gruesome forms that suffering can take. We don’t see a lot of gross deformity or retardation. We don’t see a lot of things that are kept away from us, really for our protection, so it will be more pleasant. We don’t like to think about the poverty that other people experience.

The way that our society works is that there is enough option for change. If we are aware that some people are suffering because there is a prejudice against them or some people are suffering because they are lonely, there is enough movement within our society that we can stay away from that. We don’t have to look. That isn’t the same in other societies, you have to look, and it is there. Unless you close your eyes when you are crossing the streets, there is no way that you can deny it, because it is there. So you are not particularly motivated by the fact that suffering if you do not develop the skill through the technology of practice (of insuring that you have a positive rebirth) that you could be reborn in conditions that are unbearable. We don’t accept that as being true or we don’t think about it.

We also have certain ideas that we have grown up with and these ideas are part of our culture: they are sort of children of religious systems that are inherent in our culture. They are part of what was handed to us. There is an idea that so long as we do our best and consistently stay good and improve that predictably the next moment will be a little better. I am not exactly sure how that happened but I think that it has to do with the fact that this is not, generally speaking, a culture that believes in cyclic death and rebirth. It is not a culture that understands that you have had many lifetimes before, and unless you achieve supreme realization, you will have many lifetimes yet to come.

Instead we look at the fabric of our lives and we see that children eat and they get a little bigger and they eat some more and they get a little bigger and they get a little smarter and then there is a period of decline at the end of our lives, but we don’t think about that too much. We think that things improve.

Even if you have come to accept the idea of rebirth, and that it is important, still the idea is that somehow I won’t get worse than I am. We tell ourselves it is not going to get worse than it is right now. It’s only going to improve because I am going to continue to do well and I am going to be good spiritually. I am going to be a good person and if I have already become a human being and I have these fortunate circumstances then this is all that there is so it is just going to get better.

We think this way because we don’t understand how awesome the components of the phenomena that we experience are. We think that things are so stable, that the circumstances that we experience now are the sum total of all the learning that we have ever done and all of the goodness that we have ever been involved in: all of the good and bad, it’s all been worked out. It’s only uphill from here. Basically I think that this belief is the result of an absolute marriage with the idea of linear progression. Therefore we are not motivated to practice. But this is inconsistent with what the Buddha teaches.

The Buddha teaches us that we are here through a miraculous set of circumstances because we must have done something wonderful in the past. In order to hear the Buddha’s teaching, in order to even have a shot at enlightenment, in order to not be suffering so much that it is possible to practice, to have a shot at listening to Dharma, to be able to think of helping others, we must have had an extremely fortunate past. We must have had wonderful circumstances and really have done some good. What they call good karma.

However, according to the Buddha we have lived incalculable eons. From beginningless time we have been doing this. We have experienced so many lifetimes that the causes that were begun during those times, many of them have not even actualized themselves. They are still seedlings within our mind stream. We have so many under the belt, that we literally have accumulated the causes for rebirth in the highest and most fortunate state and we have also accumulated causes for rebirth in the lowest and most difficult realms. We have all of these circumstances and somehow, almost like a gambling wheel going around we stopped at a precious human rebirth and here we are experiencing this precious human rebirth.

What makes it precious is that we have all of our faculties; we have the opportunity to practice the Buddha’s teaching. What makes it precious is that we have a shot at attaining realization and we aren’t suffering too much to do it. We have the leisure to practice. Understand that finding this precious human rebirth is, as the Buddha taught, very similar to finding a precious jewel while sifting through garbage. It is that rare. Finding this precious human rebirth with these fortunate circumstances is as common as dust on the fingernail compared to dust on the earth. That’s how many more options you had of other kinds of rebirths. If you understand how rare this birth is, you will find motivation to practice. But Westerners have a tremendous difficulty with that.

Feeling that there is only linear progression Westerners have a certain pridefulness that unfortunately says, “Well if I have what it takes to get to this point where I can think as I do and practice as I do and be as wonderful as I truly am, then surely I can keep that stuff going somehow and it will remain stable in that way.” The Buddha says not. The Buddha says that there are specific reasons that you are here and if you utilize this life to increase your merit, good karma, virtue and value inherent within your mind stream, and if you purify your mind, thereby increasing its beauty and luminosity, then you will proceed on a path that will lead to supreme enlightenment.

But think about how many people here in the West kid themselves about this. We feel safe in a life that is ever changing. We feel permanent in the midst of impermanence and we feel that we have got it knocked and we go up and down every day and then we don’t do anything to improve our state. Maybe we change a few things as a token gesture, we try to live a good life, we are nice to our kids. We are good upstanding people, but in the end we find that we have been sitting on top of a precious jewel and a fantastic opportunity, and at the end of our lives we come to a realization that we have wasted it. What has happened is that it takes such an enormous amount of good qualities, virtue, good karma and merit to have gained such a life as this and when we could have done something, when we had an opportunity to accomplish the Dharma we didn’t.

©Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

The Origin of Suffering

An excerpt from a teaching called Eight-fold Path by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

I have known of cases, it is very rare, and beautiful to behold of people who have gone through terrible terrible suffering and have used that as a way to become strong. In fact there are entire cultures of people who through tremendous need to survive and tremendous suffering, have found some way to become strong through that suffering rather than to let that suffering take them down. But that’s very rare. Most people react to suffering as though something outside had occurred to them, and they were merely standing there. They don’t understand the relationship of cause and effect, and how karma prevails, and always is exacting. If you give rise to any cause, that very effect will occur. We don’t realize that, and so we react in an odd way.

What causes our reaction is our deep attachment and desire for things to be as we wish. For instance, if we have to live on beans and rice all week because we don’t have enough money for steak and potatoes, we might think, “Oh this is terrible suffering. This is just so terrible. But then another person might say, “I really dig beans and rice. Take the Beano and you’ll be fine. What’s the problem?” I’m being funny now, but you get what I’m saying. It’s really your reaction. One person can have some catastrophe happen to them, and they will use that almost as a guru to pull themselves up by the bootstraps and get stronger. But most of us don’t. We react because we don’t have our heart’s desire. So, if we lose a relationship that is very dear to us, a death happens or loss of friendship or loss of love, when we really look from a practical sense at what changes in our lives as a result of the loss of this person, most of it is manageable usually.

What’s really terrible is our own pain. Our own pain is caused by our attachment to that person and our desire to be with that person. Attachment to a person or a desire to be with a person is not necessarily a bad or unethical thing, but understood within the context of the Buddha dharma, we must understand that too much attachment and not enough unconditional positive regard for all sentient beings – placing all of our hopes and desires on one person or maybe a small family – means that our suffering will be very great at the time of losing that relationship. We know that whatever comes together must also separate. Whether it is in life or in death, nothing remains and everything is impermanent.

It is our reaction that causes us to suffer. One person can lose a job or a position and totally flip out, and ruin the rest of his life simply by the thoughts and activities that he takes while he is not stable or in good shape. Then another person can take a challenge like that, examine himself, and say, “What’s going on here? Maybe I should change this or that about myself?” There are many ways to react, and what the Buddha has taught is that the suffering is caused by desire and attachment and the purpose of practicing the Buddha dharma is to pacify and lessen that desire and attachment. Another way to put it is to see through its narcotic effect. We want what we want. It stimulates us and makes us happy. Then we want more. But if we really examine the desire and attachment, we’ll find out that most of what we cling to is relatively unimportant and in the end, will bring us suffering because we are too attached to it. So, the Buddha taught that the origin of suffering is attachment and desire.

© Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

Back to Basics

An excerpt from a teaching called the Eight-fold Path by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

Recently it has come to me very strongly that if we lose sight or connection with the very foundations of the path of Buddha dharma, we tend to lose our way eventually. There are well-documented, well-preserved teachings that Lord Buddha gave that are very pristine and very concise. They concern the first turning of the wheel of Dharma. This is what Lord Buddha taught during the time of his life. As the Dharma grew and spread, there were other developments within the Dharma. So, there are basically three levels of the Buddha dharma. One is called the Theravadan point of view, the original teachings that Lord Buddha himself taught. There is the Mahayana point of view, the accomplishment of the original teachings, and the addition of the idea of wisdom and compassion – primarily the idea of the Bodhisattva vow – this was all taught by highly realized Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. Then there is Vajrayana, which is what we actually practice, and which has a lot of ritual to it. A lot depends on the inner rather than the outer display. It is powerful yet subtle. There is technology that goes with it, and as one accomplishes the technology, one begins to advance and change and move ever closer toward awakening.

We should never consider the first level of Buddhism to be somehow lesser. Instead we should think of the first level of Buddhism as the absolutely necessary foundation. If you don’t accomplish and don’t understand what Buddha originally taught, then there is no real understanding later on. I would consider it to be something like building a house. If you are building a house you don’t want to build it on a sandy beach where it slopes down to the sea and the waves are big. You want to build it on a very firm foundation. You want to pour your concrete slab, and make it really secure. When you are practicing the path of the Buddha dharma, it is very good to understand these primary teachings. To understand their meaning to the degree that as you move further on the path, you can always reflect back on the original teachings to give you context, strength, and inspiration. It is necessary to understand exactly what did the Buddha taught.

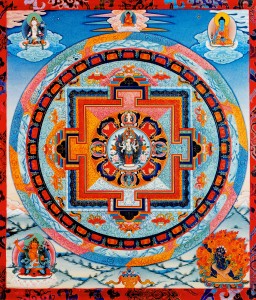

When we talk about the Buddha teaching, we say, “turning the wheel, an expression meaning, “give the dharma.” The symbol of dharma is a ship’s steering wheel, an eight-spoke wheel, and it symbolizes the eight-fold path. “Turning the wheel” is a symbolic way of saying, “teaching the eight-fold path.”

When the Buddha first turned the wheel, he taught the four noble truths. The Buddha himself was considered peerless, fully awakened, fully developed. Having experienced all of the content of samsara and nirvana, through his realization, and in his awakened state he was able to take all that he saw, and make it concise, something very understandable. Small in words, but big in meaning. This is what the Buddha taught. You can’t argue with it.

He first taught that in samsara or in life, suffering is all-pervasive, meaning that life is suffering. We don’t like to think of it that way. We prefer to think that we’re happy, and we try to coax ourselves into a happy mood. Still if we look around we see that there is suffering wherever we look. The human suffering is old age, sickness, and death. I’ve experienced two out of three, and I know I’ve done the other one but it is hard to remember. We all know that this is true. Human beings suffer from old age, sickness, and death. You can try to think positively about it, but we all know that when it gets down to it, when you’re sick, you feel rotten, and if you are critically ill, it is so much worse. It’s horrible to have your own body betray you. If you get to the point where you are experiencing old age, we can look at Madonna, and we can look at all the different wonderful people who have kept in shape and all, and we think, “Oh, its not so bad.” Its bad! Getting old is bad. For those of you who don’t believe and are too young to know, it’s bad. And that is the suffering of the human realm.

Each different realm has its own form of suffering. For instance, animals suffer from fear and stupidity. An elephant is much stronger than its trainer, and much stronger than the means usually used to contain them, but they don’t know that. Elephants are very smart in their own way, but in that particular way, they are not so smart. In India you see bullocks pulling carts and what not, and their whole life is just toil and work. They experience the whip if they don’t do it. That stupidity keeps them there. I mean, they could basically turn around and knock the driver senseless if they so chose. They are powerful animals but they don’t know that. And so that’s the suffering of the animal kingdom. That and fear since in the animal kingdom you are either prey or predator. And even predator can be prey sometimes. So fear is rampant.

The Buddha taught that everywhere you look, suffering is all-pervasive. That no matter what a person’s life looks like, there is suffering. And then he taught the cause of suffering is attachment or desire.

When we come from a materialistic society and an ordinary world, we think to ourselves, “How can that be? Suffering is when you don’t have enough money. Suffering is when you get hit by a car. Suffering is when your beloved child grows up and does drugs or something.” We can name all of these sufferings that happen to us, and so it is hard for us to understand how desire or attachment can actually be the cause of suffering. The way it is explained is that while things do happen and they are caused by our karma, the cause and effect relationships that we have given rise to in the past, and we see our karma ripening as events that seem to happen to us. What really makes us suffer is our reaction.

© Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

The Three Faces of the Path

An excerpt from a teaching called Intimacy with the Path by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

When we think of the path, we think of something that is external, separate from us, something in front of us that we have to move towards or attain. A different understanding of the path might be that the path is something that actually engages with what you might call three faces. But these three faces are very much like us. You could say that each one of us has at least three faces. Each one of has the face of anger or discontentment, the face of joy, and the face of balance or contentment. There are many different faces that we have.

The path also has faces and when we truly study them we can understand what the nature of the path actually is. You could say that the path exists as part of a three-part system and if you were to think of the path itself in a true and more profound way than we normally think, you would understand that there is no way to tell where the path begins and where the path ends. We would understand that comprising what we call the path are three faces which are (1), the ground or basis from which the path arises, (2) the path or movement itself, the display of that source or fundamental nature from which the path arises, and (3) the fruit, which is the direct result of that fundamental nature as well as the direct result of the activity of that fundamental nature.

These three things, the ground, the path and the fruit or result cannot be separated in any way, shape, manner or form. The moment that we begin to separate these three aspects, we have lost touch with what the path actually is. We have lost touch with an intuitive understanding of how to practice the path, and we experience a great deal of delusion concerning the path when we separate ourselves from the understanding of the threefold face of the path: the basis or ground; the movement or path itself; and the result of the path.

Without this understanding, anything that we do becomes a path. Any activity that we engage in becomes a method. That method connects something with something or it wouldn’t be a method. But on the path of Buddha Dharma we have to remain connected with the ground, the method, and the result. These three have to be considered as threefold.

How is it that we can use this understanding to determine the validity of the path and to remove from ourselves the tendency toward delusion? First of all there is the teaching on the relationship of the seed and the fruit. There is that kind of good old-fashioned, common-sense wisdom that if you really want to have an apple tree in your orchard, you’ve got to plant an apple seed, that if you wanted an apple tree in your orchard and were to plant cabbages, it simply would not work. You would have cabbages, not apples. If you wished for some apples and you were to plant asparagus, that’s not going to turn out really well for you unless you really determine that asparagus is your thing. I know it sounds like I’m being silly and belaboring this point. The moment we get it, I’m going to stop nagging about it, because as yet we haven’t got this one and it’s really, really important.

The Buddha Dharma is not a path or a method that arises in any common or ordinary way in the world. In other words, someone didn’t get born at some time and simply compose a path. A team of experts or technicians didn’t get together and engineer a path. NASA didn’t design this one. This path was not a dream or a vision that someone had about twenty years ago that remains unproven or insubstantial.

The path of Buddha Dharma as we know it only arises when the condition of the Buddha nature appears. It arises from the mind of enlightenment – the Buddha nature. Lord Buddha did not begin to teach the path, although he had attained varying degrees of what you might call cosmic consciousness or something like that, before he actually attained supreme enlightenment. He had various degrees of consciousness that he could communicate and various qualities that he could teach to others—teachings on compassion, Bodhicitta, practicing meditation—but in fact he did not teach until he awakened into the primordial nature that was his true nature, Buddhahood. And then at that time he was able to display the path or method to the world.

The path or method actually came forth from his realization. It did not come forth even one millisecond before his realization. Once he achieved that precious awakening, he was able to bring the path to the world. During the course of Lord Buddha’s life he discovered that there were many different displays of consciousness, many different levels of attainment and attunement that one could accomplish and he did accomplish many of these before that ultimate moment. But it was that ultimate awakening that he presented to the world as the Buddha Dharma.

The seed of the method that we practice is enlightenment, the Buddha nature itself. It is not the human nature. If it were the human nature he would have taught before that precious awakening and that would have been something from the human capacity. But it was not until supreme realization that he began to teach the method and he taught only that method which leads to supreme enlightenment. So the seed and the method are completely married and not separable.

© copyright Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo All rights reserved.

I Choose Enlightenment

An excerpt from a teaching called How Buddhists Think by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

People ask: “In your tradition, is Buddha like God?” No, Buddha is not like God. “Is Guru Rinpoche God?” No, Guru Rinpoche is not God. “Well, what do you call God in your tradition?” We don’t call anything God. There are gods, but they are not the goal. Westerners try to find a way around that, saying something like, “All right, then what is the goal?” I tell them, “Enlightenment.” They reply, “Okay, then Enlightenment is God.” No, it’s not. The goal is not anything as personalized and externalized as that. There is no “other.” The moment we are caught up in “self and other,” we have lost the essential Nature. We are fixated, stuck in duality.

This is about Awakening, which is the pacification of such fixation. You must understand the fundamental distinction between Buddhism and Western thinking––whether you are considering beginning the Path or are already a practioner. You must understand this difference, so that you will know what your true objects of refuge are.

The statement “I take refuge in the Buddha, I take refuge in the Dharma, and I take refuge in the Sangha” is an essential element throughout your practice of the Buddha’s teaching. What does this statement mean? It means you have looked at the faults of cyclic existence, and you have seen that it produces no real happiness. You have learned that the Buddha said there is a cessation of suffering, this cessation is Enlightenment, and it is also the cessation of desire. So you have decided to go for Enlightenment. That means you have to really understand the faults of cyclic existence––even if these ideas are difficult to swallow. It’s like taking a medicine that tastes bad until you get used to it. It is like that in the beginning.

Having decided to take this medicine, you look at those who deliver it. We look to the Buddha, and this includes all those who have attained Buddhahood, not just the historical Shakyamuni Buddha. We look to the Dharma, which is the revelation or teaching brought forth from the mind of Enlightenment. And we look to the Sangha, the spiritual community to which we belong. It is the Sangha who are responsible for treasuring and propagating the teachings.

In the Vajrayana tradition, we also say, “I take refuge in the Lama,” who is considered representative of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Without the Lamas, you would not hear the Buddha’s teachings. And without the Lamas, there would be no Sangha.

When you say you take refuge in all of these, what you are saying is: “I choose Enlightenment. I choose the cessation of suffering.” You move away from the faults of cyclic existence, and you remain focused on the ultimate goal.

In a deeper sense, however, you must understand that you are ultimately taking refuge in Enlightenment itself. You must understand it as both the Path and the intrinsic Nature. So you are taking refuge in the Nature of your own mind. If you understand this thoroughly, you can never be duped. But you do have to work very diligently and with discipline towards the goal.

The method is very technical, very involved. It isn’t easy because it must cut through aeons of compulsive absorption in self-nature. It must cut like a knife! It must be powerful––and it is powerful. You have to think of Dharma that way. The technology has to be strong––and real. You can’t just talk about it. There is work to be done!

Although it is strong, the technology is very flexible. You need not be afraid. You will not be forced to go any deeper than you want to go. You have the right to practice gently. You will still be accumulating causes for a future incarnation as a human with these auspicious conditions, and then you will be able to practice well and dilligently.

There are people who only do very small, very gentle practice. And that’s fine. There is a large tradition of that in the Buddha Dharma. There are also people who are more deeply involved, though in a mediocre way. They practice an hour or so a day. They do a good job, and they’re faithful, and that’s it. Then there are people who practice many hours each day. They continually try to propagate the Teaching, and they work very hard. So you have a choice. You can determine the level of your involvement.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

To download the complete teaching, click here and scroll down to How Buddhists Think

The Benefits of the Awakening Mind

Here is another excerpt from the first chapter of A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life called “The Benefits of the Awakening Mind.” May these words written by Shantideva inspire all who encounter them.

#26

How can I fathom the depths

Of the goodness of this jewel of the mind,

The panacea that relieves the world of pain

And is the source of all its joy?

#31

If whoever repays a kind deed

Is worthy of some praise,

Then what need to mention the Bodhisattvas

Who do good without it being asked of them?

#32

The world honors as virtuous

One who sometimes gives a little, plain food

Disrespectfully to a few beings,

Which satisfies them for only a half a day.

#33

What need be said then of one

Who eternally bestows the peerless bliss of the Sugatas

Upon limitless numbers of beings,

Thereby fulfilling all their hopes?

#34

The Buddha has said that whoever bears a harmful thought

Against a benefactor such as a Bodhisattva

Will remain in hell for as many aeons

As there were harmful thoughts.

#35

However, if a virtuous attitude should arise (in that regard),

Its fruits will multiply far more than that.

When Bodhisattvas greatly suffer they generate no negativity,

Instead their virtues naturally increase.

#36

I bow down to the body of those

In whom the sacred precious mind is born.

I seek refuge in that source of joy

Who brings happiness even to those who bring harm.

Seed of Your Buddha Nature

When one begins to understand some of the ideas that are presented in Dharma, one realizes that the goal that we are engaged in “moving toward”, if you’ll forgive that bad choice of words, is actually Buddha Nature itself. We tend to consider that the path is like a thing that goes from here to there, like a movement toward, and it’s very hard not to conceptualize it in that way. But, in fact, when one practices Dharma, the ability to practice Dharma is actually based on the understanding of the innate Nature. If we did not have within us right now the seed of Enlightenment, if we did not have within us the potential to actualize ourselves as the Buddha, there would be no point of practice. The very basis for practice is that understanding.

This is what the Buddha himself taught – that all sentient beings have within them the seed of Buddha Nature, that that Nature is their true Nature, in fact. However, they have not awakened to that Nature and so, in order awaken to that Nature, one engages in the path. The path should not be considered a ‘thing’, a straight line that connects from here to there. The path should be understood as a method that one uses in order to awaken to that Nature which is already our Nature; which is complete, unchanging, and will never get any bigger or any smaller. One should understand that Dharma is actually an activity that is meant to awaken that potential. But the ultimate goal that one wishes for when one engages in Dharma is, of course, Enlightenment itself. Now, what is Enlightenment? One understands that Enlightenment is actually the awakening to the Primordial Wisdom Nature, the awakening to the Buddha nature.

The Buddha never said that he was different from anyone else. He said simply, “I am awake”. He is indicating that he has awakened to the fullness of his own Nature and is able to abide spontaneously in that awakened state without any interruption or impediment. So, from that perspective, the basis of practice, the basis of the path itself is exactly the same as the goal. They are indistinguishable from one another. The path that one uses in order to achieve the goal is also indistinguishable from the basis, which is the Buddha Nature, and is also indistinguishable from the goal, which is the Buddha Nature. So, these three things, the basis, the method and the goal are indistinguishable from one another.

For us, however, it does not appear to be so, simply because of the way our minds work, involved in discursive thought as they are. We distinguish between what is potential and movement. We distinguish between movement and the goal. But in truth, you cannot distinguish between these three. If the basis for practice is the same as the goal, then anything, in which you engage in order to achieve that awakening to your own Nature, must also be indistinguishable from your own Nature. The path, then, or the method, is not separate from the Buddha Nature.

Now, where we run into trouble is when we make our Dharma practice an outward movement that goes somewhere. When we do our practice, we project that there is going to be a certain result. That very subtle concept prevents the practice from doing all that it can do to remove obstacles from our own perception, because we cling to the idea of here-ness and there-ness, of such-ness and thus-ness, and in doing so, we cling to the idea of self. It’s very hard to understand that subtle difference, but that subtle difference is very important. If we did not view our Dharma practice as a subject, object, thing or as a linear movement in some way, we would more easily understand that the goal is the un-moveable, unchangeable, fully complete and spontaneously realized Nature itself, which is already present. The potential for the realization of that Nature would be much stronger in our practice, in terms of taking responsibility for our situation and utilizing our practice to its fullest capacity.

In order for us to consider our Dharma practice, or even the ability to listen to teachings, as a movement that ‘goes somewhere’– we have to be considering it in a very superficial way. But if the practice is understood as a natural and spontaneous manifestation, arising from the Buddha Nature that is our Nature, then the practice becomes less materialistic and more meaningful in a very profound way. In the same way, if we are in an ordinary environment and an ordinary teacher comes before us, we don’t respond as we would if the Buddha himself, with all the signs and marks, were sitting in front of us. If the Buddha appeared, we would respond with, “Whoa! Whoa! This is important! Something is happening here. The Buddha is here!” In truth, we should respond that same way to our own simple practice because that practice is indistinguishable from the Buddha Nature itself. The Buddha is here. But you see, the impact is different. Why the impact is different is in the way that we consider and the way we have our understanding about what we’re doing.

©Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

Excerpts from A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life

A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life

by Shantideva

Chapter One: Benefits of the Awakening Mind

#5

Just as a flash of lightning on a dark cloudy night

For an instant brightly illuminates all,

Likewise in this world, through the might of Buddha,

A wholesome thought rarely and briefly appears.

#25

This intention to benefit all beings,

Which does not arise in others even for their own sake,

Is an extraordinary jewel of the mind,

And its birth is an unprecedented wonder.