The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Marrying a Spiritual Life with Western Culture”

What is the missing link? What causes us to shunt ourselves off in that direction and create a scenario whereby we either don’t relate deeply to our path or it cannot nourish us, or we find ourselves feeling dead inside? How does that happen? One of the things that you have to remember—and it’s really important to think about—is that it is more and more prevalent in modern society to not see some of the natural currents of life. This is particularly true in our country with our level of technology and all the civilizing factors that have come together to make us what we are.

For instance, here we are so technologically advanced and removed from certain natural occurrences that we rarely have the opportunity to see the beginning of life carried all the way through to the end of life. Unless we ourselves have had a baby and daddy went into the birth-giving room and mommy had a mirror—unless we do that—birth to us is a mystery. We do not see what birth looks like. We have pictures of it. We may have seen a movie, but the direct sensual experience of seeing, hearing, touching, tasting and smelling, we have not experienced. Even those of us who are parents are somehow absent from this experience because many people do not have a real direct experience of their own birth-giving. They go to sleep during it or they’re drugged or something like that.

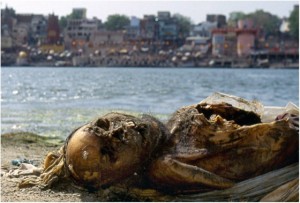

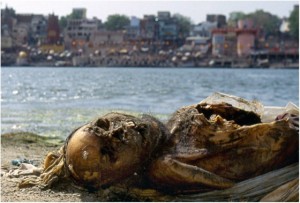

Neither do we have an experience of dying. When we die, we will have that experience; but until then, it’s hidden from us. We have no way to prepare ourselves for the reality of death in our society. We have no way to understand what is gained and what is lost during a life. Watching someone die is an interesting experience because you can see that everything material is left behind. You have a sense, once that consciousness has left the body, has moved on, that there is a really distinct difference between what the body is like at the door of death—even if it was unconscious—and what it’s like after consciousness has actually left. It’s quite different. Any of us who have seen loved ones immediately after their death will know this. You know that there is nothing in there, unless you’re completely out to lunch, which I also have seen! But you can see that something essential has left and that everything material has been left behind. It’s such an eye-opener, particularly if the person who has died is not very old. Perhaps they were still at the point in their life where they took a great deal of pride in their body or thought of themselves as being very vital. You might remember different things about the person. You might remember that the person didn’t like their figure, felt that they were too fat. Maybe you know that during the person’s life they obsessed about this. They felt really bad about being fat and they tried to do things about it without success. Then you see that person die. When the consciousness leaves, you realize that everything they struggled with doesn’t matter. Whether that body was fat or skinny, it didn’t go with them.

An understanding of how superficial such a struggle is occurs when you naturally see the rhythms of life and death. Do you see what I’m saying? There is a natural understanding that no one else can teach you. You have to see it yourself.

To understand what we are, it’s also good to see a number of babies being born. Babies are different when they are born. Hospital nurses who care for babies right after they’re born can tell you this for sure. Babies are not blank slates. Some babies are very aggressive and very active, and you can tell that they have tiny, little, confrontational personalities already. They’re just that way. And then other babies are just wide-eyed and open. They’re like little jelly fish. My two sons have always been polar opposites—from the first moment they were born. A mother who has had more than one child can tell you that’s how it is.

Many of us are completely separated from these natural events, yet they teach us very profound things about how to approach spirituality. Even the story about the Buddha indicates this. At first the Buddha was prevented by his father from seeing the suffering of old age, sickness and death. After having witnessed these sufferings, he found the strength to go on in his path because of compassion, because of the deeply felt recognition that occurred to him on some subtle level. That’s a metaphor for the problem of our society. What a display Lord Buddha gave us when he showed us that, because on several different levels we are prevented from seeing suffering by our society.

We take dead bodies away and put make-up on them. (Can you believe that? I want all my make-up on my body before I die. I do not want someone to put it on after I’m dead. All of you can remember this? That is not the time for a face lift.) On an internal level, because of these subtle messages that we get, we do not come in contact easily with any real internal processes. We avoid them in the same way we are taught to avoid them externally. We’re told, “Don’t go there, it’s not safe. Just don’t go there!”

We are told not to approach things in a really intimate way. Now in the story about Lord Buddha’s life, when he saw the suffering, it bothered him, hurt him, upset him, scared him and shocked him, and he had to—oh my—go through transformation, that “T” word that scares us so much. Transformation is related to change, the other word that really scares us. So, yes, he had to go through all of that, but what was the result? The result was he became deeply empowered and was able to make some very difficult choices.

He decided not to live an ordinary life in which he was extremely happy. He was a prince with all the blessings. He loved his family. He had a beautiful and devoted wife, and they were very close, very intimate. He had a beautiful newborn child and was not a distant or absent or unconnected parent. He loved his greater family as well, his father and mother—the king and queen. But for the first time he saw the suffering of old age, sickness and death, and it moved him to his core and enabled him to make choices that are very difficult. He came to the point of deep knowing within himself, that if he wanted to really love his wife and his baby, he had to find the way to liberation for their sake. The phrase “for their sake” became real to him. It’s not real to us.