The following is an excerpt form a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Commitment to the Path”

I like to see students start off kind of smallish and grow bigger in their practice, because I think that is more realistic. The best way to start out our practice is to understand what Dharma is trying to accomplish—what are the faults of cyclic existence and what are the results of practicing Dharma—to get a clear idea of that so that we can see for ourselves that this is a beneficial thing, so that we don’t have to argue with ourselves further down the path when it’s not appropriate any more.

So these teachings that I would like to give you are designed to get you to progress. They are made to get you somewhere. You are not meant to stay where you are on the path. One progresses and that means change. You know, that scary word. So we have to ask ourselves then: What is Dharma engineered to do? How does that change take place? What does it look like? What does it mean?

Well, first of all, look at something that is not Dharma. Look at whatever sense of spirituality or religion you have that is not Dharma. If we look at the ideas that we have generally as a culture about spirituality, spirituality is like salt. It’s a condiment, a little ketchup on the hot dog of life. It’s a flavor, but it’s not nourishment. It doesn’t give you what you need every moment of every day necessarily, unless you yourself find a way to relate to that faith so strongly.

With Dharma, it’s a different story. You don’t ever have to feel your way around. You are never walking around in gray zone. You can do practice. You were taught how to increase your knowledge and your wisdom. You go from one practice to another to another to another through the different levels. You can move through them according to your habitual tendency and your karmic propensity. So there is something exacting, something like a method.

The reason why is that Dharma is not meant to act as a barbiturate, to calm you. It’s not Valium. It’s not meant to soothe you and make you feel more comfortable. It’s more like if you could imagine your life as being a dark room, like any other room—filled with furniture. And it’s very dark. You can’t see a thing. This is kind of your life as a sentient being, because we really don’t come into this world understanding anything about cause and effect or how to make ourselves happy. We come into this world unknowing, with only habitual tendencies. That’s all we come in with, deep habitual tendencies from previous experiences.

So in a way, our lives are like this dark room, filled with obstacles. By now, now that we’re getting a little long in the tooth, we know there are obstacles. We’ve had them. Some of them, anyway. Doubtless there are more to come. So we think of our life like this room with furniture in it and you’re supposed to get from the birth door to the death door successfully and make some progress in the meantime. Well, if it’s pitch black and there are all these things in the room, the chances that you are going to walk through without knocking yourself into oblivion are pretty slim. So the way that Dharma works is it forces you to turn on the lights. You have to look at obstacles. You have to look at what is in that room. With another kind of faith you might think that the best thing to do is think positive and be positive and plaster good thoughts on your head. You know, just try to be kind of upbeat and make the best of everything. All good ideas. But when you are stumbling through a pitch black room and there is a lot of furniture in there, you are going to trip. And no amount of positive thinking is going to get you through that room successfully. No amount of positive thinking is going to keep you from entering that last door. Nobody has done it yet through positive thinking.

So Dharma’s tendency, rather than act like a soother or a barbiturate or something that is calming, Dharma turns on the light. Dharma says, “Look folks, here is what’s happening.” You are born, but you don’t remember how you got here. There are uncountable cause and effect relationships since time out of mind that have formed into habitual tendencies and karmic propensities. And here you are born as a child. How did you get those parents? How did you get in this world? How did this happen? That’s what I said when I woke up as a kid. What’s wrong with this picture?

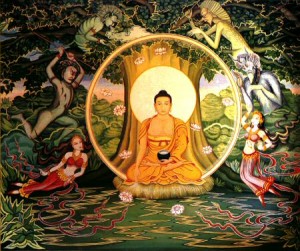

So we find ourselves here and we’re kind of helpless. That’s one of the teachings that the Buddha gives us. That in truth, we are all the same and in our nature we are exactly the same; but in our ordinary appearance as sentient beings, we are in a state of confusion. We do not understand cause and effect relationships, because we can only see this present lifespan. We have had so many lifespans to give rise to causes in an amazing amount of time, since time out of mind. So we have no understanding of this.

Dharma teaches us that all sentient beings, while we are the same, and while we are wandering in confusion, have one thing in common and all of our activity is geared towards that. And if you think about it, you know that it is true. Even when we are doing for others, until we really have given rise to compassion, we’re always trying to be happy. It’s natural. The organism wishes to be balanced and at peace, happy. But we don’t understand what balanced and at peace is. So we keep grabbing for stuff. Yet Lord Buddha teaches us all that we are suffering due to desire. It’s not that you don’t have something that makes you suffer, but your reaction to the not having it…that is most of the suffering.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo All Rights Reserved