An excerpt from the Mindfulness workshop given by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo in 1999

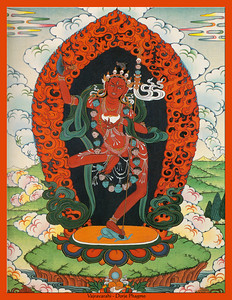

In our Ngöndro practice we find the practice of offering oneself, the practice of generosity. It’s called the practice of Chöd. Chöd can very easily be practiced constantly. The practice of Chöd is based on eliminating ego-clinging through transforming oneself into that which is beneficial to all sentient beings and offering oneself. In Chöd there is actually a visualization where you see all your different elements separated into piles: skin and bones and muscles and fat and eyeballs and stuff like that. All of that stuff is put into little piles and you cook it all up and you offer it up to the Buddhas. And you’re thinking, “That’s kind of an interesting little practice there, isn’t it? Whoa, dude!” But just remember that this is meant to antidote our ego-clinging because as we walk through our lives, we are all about ‘what can you do for me, and what do I want?’ Remember, as we’re walking through our lives as ordinary sentient beings, our mantra is “Gimme gimme gimme, I want I want I want I want.” So this kind of practice is meant to antidote that.

The very habit that we have of assuming self-nature to be inherently real and reacting with hope/fear, want/not-want to our environment and the things in it constantly perpetuates itself! So, we are taught instead that, wanting to make oneself useful in some way, wanting to be of benefit and awakening compassion, one way to practice that is by offering the self, offering self-nature, and transforming it into something that is useful to sentient beings.

So how can we do that as we’re walking around? Try to remember that we’re practicing Recognition. Here’s a great way to think about it. Have you heard about the guy who recently had a cadaver’s hand sewn onto his arm, and it’s working? Now those of you that have heard about that, what did you think about that? You probably said, “Ugh!” I mean, it sounds amazing in one way, doesn’t it, that somebody who didn’t have a hand now has a hand, but it’s not his hand. So when we think about it, that’s kind of gnarly, right? Just think about it: you know what your hand looks like. You’ve seen it your whole life. It changes, but it’s your beloved hand. It’s so recognizable. It has a certain shape, and it feels a certain way. Well, now suppose you had an unmatched set, and one of them was not your hand. Think how you’d feel. This kind of clinging is so automatic that until we hear something like that, we don’t even know we do it. It is the very basis for our recognizing one another and ourselves as selves.

We grow attached to the shape of our face, the shape of our head. Even if we don’t like the shape of our face and the shape of our head, we grow attached to it because it is us, (we think), and so it constantly perpetuates that idea of self-nature being inherently real. It constantly perpetuates that ego-clinging. Our bodies are, for us, something that we have to protect. Even if you think that you’re very brave and not afraid of being hurt, or not afraid of even losing your life, I say to you, baloney! I’ll start chopping, and you tell me when to stop. We protect our bodies. If anything scary comes around us, we react, “Aaaggh!” And if we can’t protect ourselves any other way, we protect our head because that’s the part that keeps us going — we think. So we have this automatic clinging. Any sense of recognition of oneself as self is a clinging kind of phenomenon.

To antidote that, we practice Chöd, separating all the parts. When you’re done separating all the parts, you can ask yourself, “Well, what part am I? The skin or the bones or the fat or the muscle or the brains or the tongue or the eyeballs? Which part am I?” Of course, we begin to learn that that question is not answerable because ‘I,’ or self-nature, is simply a concept. It’s simply a concept.

How can we practice this as we walk around through our lives? Well, one way to do that is to develop the habit of when it is you notice yourself…do you notice yourself? You notice yourself constantly! It’s all you notice. We notice our hands; we notice the position that we’re in; we constantly move to be in a different position, don’t we? We think, “Do I want my hand like this or like that?” We are constantly doing that. It’s a constant phenomenon.

Suppose we were to develop the habit of considering the hand. “Well, this one matches that one. I like that.” But what if we were to consider our hands in a different way? Instead of thinking, “This hand is mine and it looks like this,” think, “How can this hand be of benefit to sentient beings? What use is this hand?” Consider it. You can develop a sense of Recognition of the true nature of our body parts. You can think to yourself, “Do you know what I like best about me? I really like my eyes.” I like your eyes too, but I like my eyes, and so when I think about that, I think, “Oh, you know, wherever I go, I have these eyes, and they can see. That’s really cool. And other people can see me.” And I can work those eyes, can’t I? And that’s really something. All we know is that our sight, our eyes, are part of us: that is us. We cling to that. Suppose we were able to understand our eyes in a different way. Supposing when we think of our eyes and how wonderful the capacity to see is, or how amazing it is that we can express ourselves with our eyes, we can offer that entire scenario, that entire experience, to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas for the benefit of sentient beings. Your relationship to your own body parts, your own eyes, for instance, your own hand, becomes different. Rather than thinking, “These are my brown eyes and I have great brown eyes,” or “This is my right hand and it’s a great hand” — rather than thinking like that as an extension of our ego, we can develop the habit of offering the whole phenomenon of sight, the whole relationship to our different body parts, by evaluating how it is that these eyes can benefit sentient beings, and how it is that we can offer them.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

Thank you, Precious Lama. This is a practice I can incorporate with my role of carer. As always, your teaching meets my current need.