From The Spiritual Path: A Compilation of Teachings by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

Wouldn’t you think it impossible—in a country so permeated with eternalism, with the traditional western teaching that the self exists after death—for many people to act as if they believed that it doesn’t really matter what they do? Yet these opposing beliefs coexist in our culture. It is somehow possible for us to believe in eternalism and at the same time to be full-fledged, card-carrying materialists. Let us examine how this has come about.

Very early in life, we learn about rules. Getting caught with your hand in the cookie jar means trouble. Also, our parents hide their feelings and teach us to repress ours. We see them break laws sometimes, clear-cut ones. If we ask our parents why they just ran a red light, they may jokingly say, “It was only pink.” We also see them do things they told us not to do. (“Do as I say, not as I do,” they seem to be teaching us.) We soon realize that there are some things we can sweep under the carpet of our conscience.

We also learn about cause and effect. We know that if we cross a busy street without looking both ways, we may get hit by a car. Fire burns. Immediate, obvious consequences we understand. What we neglect, what we do not really comprehend, is that results can take a long time to unfold. Early in childhood, we were told not to feel anger, yet we could sense it in adults. How do you feel a certain way and yet not feel that way? We learned the real message: if you can see it, it counts; if you can’t, it somehow doesn’t. It’s okay to get mad and to hate if you don’t do it too obviously. Taking an ax to people or beating them up is wrong; but somehow you can get away with being angry at them. We learn that it’s okay to do subtle or secret things.

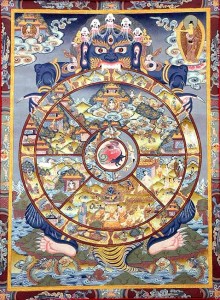

Being subtle is not a problem. And there may be nothing wrong with hiding feelings. The real problem is that we fail to understand that hatred and anger will produce results simply because they exist in our mindstreams. Even though hidden or subtle, these feelings create an undeniable cause-and-effect relationship. People in Buddhist or Hindu countries deeply believe in karma. Whether or not you get caught makes no difference. They know there is absolutely no way a person can get away with anything. They are taught from birth that if you don’t pay in this life, some day you will. This is so profoundly ingrained that they have a totally different perspective: health, appearance, prosperity, surroundings, family, the ability to be successful in our lives—all these are seen as results of previous actions.

We, however, are convinced that our experiences happen to us. If someone is angry at us, we can find the causes, can’t we? The person was in a bad mood. Well, if we’re honest, we might remember that we said something to him last week, and now he’s getting back at us. Anyway, we can always find something. But what we are experiencing is not what it seems. It is a picture, a display, an emanation of our own mind-stream continuum. And if we are experiencing it, we had something to do with sowing the seed, which is now ripening. That is what the Buddha teaches.

This is true of every event, such as people treating you badly, or even an experience like hunger. My stomach is empty. I need food. But this experience and all the circumstances surrounding it are the ripening of previously created karma. We can’t see at that subtle level because we have no sense of our true nature. We cannot see the continuum. We can see pieces of it, glimpses maybe; but the continuum is invisible. So we persist in our habit of inventing explanations.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo