OM TARE TUTTARE TURE SOHA

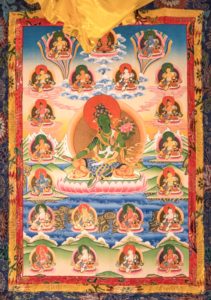

21 Homages to Tara PDF Download

A sacred space for everyone

An excerpt from a teaching called How Buddhism Differs from Other Religions by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

We tend to do things that give us a rush, but it doesn’t make us happy. For instance, let’s say we decide to drink some alcohol, and we decide to do it a lot, and we decide to get loaded every weekend, and we think, “Boy, you know that gives me something to look forward to because all week long I can be a good person, and then on the weekend I can get loaded, and then I’ll be happy.” Of course, it doesn’t happen. Generally, what happens is your body gets sicker. You get dependent on alcohol in order to feel anything. And you know eventually the mind just churns in samsara and no new habits or no new understandings or anything that will actually make you happy occurs. We just get drunk. And then we sober up on Monday. And that’s it. That’s all that happens. But we keep thinking that if we do it every weekend, and if we do it better every weekend, then eventually one weekend it’s really going to make us happy, and it’s going to last. And of course, that’s foolish because it never works. There’s something about human consciousness that makes it difficult for us to learn from experience. It’s like banging into the wall constantly. And we go on with behavior that actually makes our situation worse rather than easing it or making us happy or making it better in any way.

For instance, let’s say you really feel that you would be happy if you had more money. I can’t say that I haven’t thought that. And I’m sure if I’ve thought that, pretty much everybody has thought it at least once. And so we think, “Wow, if I had some money, I could do some things, and I would be happier. I’d really like to go on vacation this summer, and there’s no money to do it with so wouldn’t I be happy if I could go on vacation.” It’s that kind of thinking. Let’s say that you put a lot of energy into getting this money. Let’s say in fact that you put so much energy into it that you’re not quite kosher about it. You’re not quite above board. Let’s say you lie a little. Somehow that brings you a little money. Let’s say you cheat a little. Somehow that brings you a little money. Let’s say you steal a little bit. Somehow that brings you a little bit of money. You may get the money. You may go to jail too. You may get the money and you may go on vacation, but guess what? You have set yourself up for more suffering than you could possibly imagine, because even if the vacation goes well, the moment that you took from others, and were dishonest and acted selfishly, at that very instant when you gave rise to a negative cause, the result was also born. Did you know that? We think we get away with it until we get caught. And it’s not true. The moment we create a nonvirtuous cause, the result is born – at the same moment.

In our lives it seems different because it seems like time is linear. And it seems like you were really nonvirtuous on Thursday but by Saturday it is still looking good for you. So you think, “I got away with it.” No, it doesn’t work that way because you gave rise to the cause, so the result is already there. Just because it didn’t ripen on Saturday means nothing. It will happen. You will have karma with the person that you were dishonest with or that you stole from or that you harmed in some way, and that person will harm you in the future, whether they want to or not, it will happen, because karma is exacting. It’s cause and effect.

If you can understand how a seesaw works, you can understand how karma works. If you can understand how you could drop a rock on one side of the pond and feel the vibration on another side of the pond, then you understand how karma works. Although we can’t see it manifesting in front of our eyes, that’s our great loss because we still think we get away with it. And it’s simply not true. Let’s say we go ahead and steal, we go on vacation, and we think it all works out, and then six months later, something dastardly happens to us. And maybe it reminds you a little bit of the situation in which you were not nice to somebody, and maybe it doesn’t. If you do catch the connection, bully for you. You’ve learned something and that’s excellent, but if you don’t catch the connection, and most of us don’t, then it’s unfortunate.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love series

All of our suffering is brought about because we have desire in our mindstreams. Having desire, we have attachment and aversion, hope and fear. Examine your own thoughts. Every one of them is either a thought of hope or a thought of fear. There isn’t one that doesn’t have as an underlying cause of hope or fear, attraction or aversion. Every one. That is the way the mind of duality works. So all of the experiences that we have, according to the Buddha, are caused by the karma of desire. Making wishing prayers to return in a form in which you can benefit beings purifies the mind of desire. You will find that desire rules your mind less and less. Compassion is the great stabilizer of the mind.

Never stop cultivating aspirational Bodhicitta. While you are practicing aspirational Bodhicitta your mind becomes firm and stabilized. You are so on fire that you need to practice, in the same way that because you are determined to live, you always remember to breathe. With that intensity, you should be absolutely determined to accomplish compassion and benefit all beings. You always remember to practice and be mindful. Then you begin to practice practical Bodhicitta.

Practical Bodhicitta has two divisions. It has a lesser and greater division, or personal and a transpersonal division. Compassion on the personal level is what we call ordinary human kindness. It is invaluable. There is never a time in your life that you should not practice ordinary human kindness. I am sometimes dismayed at people who have a high-fallutin’ idea about compassion and how to practice the Vajrayana path, and they know how to do the proper instrumentation and they can chant and they can do all these wonderful things. But they aren’t kind to one another. How you can think of yourself as a real practitioner and not even be nice to the person next to you? How can you be arrogant?

Ordinary human kindness must be constantly practiced. If you know of someone who is hungry, you should do your best to feed them. If a starving child were in front of you, wouldn’t you feed him or her? If someone that you loved really was lonely, wouldn’t you try to help them? Of course, these are ordinary human kindnesses. We’re not even perfect in that, are we? I mean, we let ourselves and our families down. We let everybody down on a regular basis. Sometimes ordinary human kindness is impossible to achieve.

Ordinary human kindness is not lesser in its fabric or nature, but it touches less people. For instance, let’s say you needed a friend. If I were to stay with you for some period of time, we would talk and we would share. Maybe I would teach you to meditate, if I were to discover that you’re the kind of person that would really respond to that. But if I don’t do that, maybe I’ll have the time to teach a large group of people. Essentially I might be able to benefit many people as opposed to benefiting one person, even though you are very important and precious to me. Yet even teaching a larger group of people is actually an intermediate level of practice. There are only so many people that can fit in this room and can be taught.

What is the highest level of compassion? What is the highest level of Bodhicitta? You have to go back to the Buddha’s teaching to figure this one out. The Buddha says that all sentient beings are suffering and that there is an end to suffering and that the end to suffering is enlightenment. That’s the only true end to suffering. If you fed every one that’s hungry everyday and provided them each with a companion so that they’re never lonely, gave them nice clothes, they still will experience old age, sickness and death. There’s nothing you can do about that. And you have no control over how they will be reborn in their next incarnation. They could come back in a form in which they still suffer. The only end to suffering is to eradicate the cause of suffering from the mindstream.

The root cause of all suffering is the belief in self-nature as being inherently real. It’s the mother of all-pervasive desire in the mindstream. The children are hatred, greed and ignorance. The mind of duality causes us to act in certain ways that create the karma so that our lives manifest in certain ways. If we suffer from hunger or old age or sickness or death, whatever it is that we suffer from, the root cause for those sufferings is the belief that self-nature is inherently real. How can you possibly uproot all of that from your mindstream? How can you rid the very seed of suffering from your mindstream? According to the Buddha, that is to achieve enlightenment. To help sentient beings remove these causes from their mindstreams, we must ourselves first achieve enlightenment. The purpose of self, which is to achieve enlightenment, is the same as the purpose of other, which is to achieve enlightenment. They are the same, in the same way that we are non-dual, these purposes are non-dual.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love series

In the Vajrayana tradition one contemplates very deeply on certain thoughts before you ever go on to any deeper practice, and these thoughts are called the ‘Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind.’ The idea is that your mind becomes turned in such a way that your intention to practice is firm, like a rock. If you were wishy-washy about why you should practice meditation, your meditation will be wishy-washy. There’s no doubt about it. If you were convinced that your job could bring you more eternal and natural happiness than enlightenment, you would practice your job with greater fervor than you would practice enlightenment. Therefore you try to turn your mind so that it has a firm foundation, hard as a rock, upon which you can build your practice.

It’s that way with aspirational Bodhicitta. You have to turn your mind in such a way that you understand the value of compassion and you have to actually ignite your mind. You have to set it on fire, and that fire has to be stronger and hotter and fiercer than any other feeling or idea that you have. It has to burn so strongly that you can’t put it out.

In order to practice aspirational Bodhicitta, you must first of all look around you with courage. Because we Americans, even New Age Americans, don’t like to look around and see that others are suffering. We hate to think about that. We think somehow it’s bad to think like that. According to the Buddha, it isn’t bad to think like that. In fact, you must think like that in order to go on to the next level of practice. You must look around you and be honest and be courageous. If you don’t see suffering in your life, if you don’t know that the people around you are lonely or getting old or getting sick, that they live with worry and with fear, then what you need to do is go to the library and check out books about other cultures and other forms of life, and see what the rest of the world is like. Have you ever seen pictures of Calcutta, India? Have you ever seen pictures of Bangladesh? Have you ever seen pictures of Africa? If you don’t believe that suffering exists in the world, you’ll see it there. Have you ever studied the lives of people who continually do non-virtuous activity? Even though they might look like they’re tough and in control, they are deeply suffering. It behooves you to be courageous enough to examine that. You should look at other life forms. You should look at animals. You should look and see how oxen are treated in India. I speak of India a lot, not because it’s a bad place, but because I’ve been there, and I was shocked. I had no idea how sheltered Americans are from suffering. I had no idea until I saw lepers in the street with no limbs and with open sores.

Having studied these things, you will come to understand that there is suffering in the world. You should cultivate in your heart and mind a feeling of great compassion. You shouldn’t stop until you’ve come to the point that you are on fire and you cannot bear that they are suffering so much. The Buddha says that we have had so many incarnations in so many different forms that every being you see, every one, has been your mother or your father. Whether you believe that or not, it’s a great way to think. Because you look at other beings and see how they are suffering helplessly, with no way to get out of it. And that they, at one time, had given you birth. In that way, you can come to love them in a way that you can practice for them.

You should allow yourself to become so filled with the urgency to practice loving that your heart is on fire and there’s no other subject that interests you as much. Even if it’s uncomfortable; we Americans think we should never be uncomfortable. Sometimes discomfort is very useful. Be uncomfortable and let yourself ache with the need to practice Bodhicitta. Cultivate in yourself that urgency and that determination. You might get to the point where you feel something, and you feel sort of sorry for all sentient beings. You might think, “Okay, now I’ve got it. I’ll go on to the next step.” No, you haven’t got it. You should cultivate compassion from this moment until you reach supreme enlightenment.

Unless they are supremely enlightened no one is born with the perfect mind of compassion. I, and everyone I teach and everyone I know, including my teachers, practice aspirational Bodhicitta everyday, reminding ourselves that all sentient beings suffer unbearably and that we find it unbearable to see. You should continue to cultivate compassion every moment of your life. It will begin to burn in your heart. It’s like love. It’s beautiful. You won’t want ever to be without that divine fire in your heart. It will warm you as no other love can. It will stabilize your mind as no other practice can.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

OM TARE TAM SOHA

[Adapted from an oral commentary given by His Holiness Penor Rinpoche in conjunction with a ceremony wherein he bestowed the bodhisattva vow upon a gathering of disciples at Namdroling in Bozeman, Montana, November 1999. —Ed.]

In general, dharma consists of many divisions and distinctions of spiritual teachings, while at the same time the nature of all dharma is that it has the potential to liberate beings, both temporarily and ultimately, from the suffering of cyclic existence. The main cause or seed for that [liberation] is the cultivation of bodhicitta. Various traditions exist for the bodhisattva vow ritual and training. The lineage for these particular teachings, which was passed from Nagarjuna to Shantideva, is known as the tradition of the Middle Way as well as the lineage of the bodhisattvas.

There are four aspects related to receiving the bodhisattva vow: receiving the vow itself, ensuring that the vow does not degenerate, repairing the vow if it is damaged, and methods for continuing to cultivate and maintain the vow.

The first aspect of receiving the vow itself has three aspects: the individual from whom one receives the vow, oneself as a qualified recipient, and the ritual for receiving the vow.

First, the individual from whom one receives the vow must have strong faith in the Mahayana vehicle and must be a true upholder of the vow. He or she must be someone within whom the vow abides and should also be someone who is very learned concerning the vehicles, particularly concerning bodhisattva training. Such a person must never abandon bodhicitta and must always keep the vows pure, even at the cost of his or her own life. That individual must also be a practitioner of the six paramitas of generosity, morality, patience, diligence, meditation, and prajna, and must never engage in any activity that contradicts them.

According to the tradition of Nagarjuna, the way to receive the vow for the first time is from a spiritual guide. Later, if an individual’s vows[1] degenerate, and if a spiritual guide is then absent, that person can restore the vows in the presence of an image of the Buddha. It is not necessary that they be restored in the presence of a spiritual guide.

The second aspect for receiving the vow itself concerns the individual who qualifies to receive it. According to the tradition of Nagarjuna, all sentient beings who desire to receive the bodhisattva vow qualify to receive it. The only exception is types of gods in the formless realm, called gods devoid of recognition, which are gods that lack cognitive abilities. With this one exception, basically all sentient beings qualify to receive the vow. But those who qualify in particular are those who have supreme knowledge, which refers to those who know what the bodhisattva vow is and what the benefits of receiving and maintaining it are. Such individuals are particularly worthy recipients because they have profound compassion and are able to use that compassion to bring both temporal and ultimate benefit to other beings. In short, any individual who has an altruistic attitude and wishes to take the bodhisattva vow qualifies to receive it.

The ritual [which is the third aspect of receiving the vow itself] also has three parts: the preliminaries, the actual ritual, and the concluding dedication. The preliminaries have four parts: adjusting one’s own intention, supplicating the objects that confer the vow, taking the support of refuge, and practicing the method of accumulating merit.

First [during the preliminaries] one adjusts one’s intention [in order] to be in harmony with the special feature of this instruction. There are three ways to do so: by developing repulsion or weariness toward the suffering of samsara, by developing an attraction to enlightenment, and by transcending the two extremes of samsara and enlightenment through vowing to maintain the middle way.

When considering the first step to adjust the mind, one cultivates repulsion and weariness toward samsara as antidotes for strong attraction to worldliness, to ordinary phenomena, to one’s own life, wealth and endowments, and to one’s friends and loved ones. Through cultivating weariness toward the suffering of samsara, we learn about impermanence and come to understand the impermanence of all worldly phenomena.

[The second way to adjust one’s intention in order to be in harmony with the special feature of this instruction is through] developing attraction to enlightenment. According to this tradition, what leads one to develop an attraction to enlightenment is the cultivation of love for all beings, which one begins by contemplating the suffering of cyclic existence and then cultivating repulsion and weariness [toward that existence].

This leads to the third stage concerning the aspect of adjusting one’s intention [which is the first of four aspects of the preliminaries to the ritual for receiving the vow]; transcending the two extremes of samsara and enlightenment by vowing to maintain the middle way. The practice of the enlightened mind, bodhicitta, involves two levels, the aspirational and the practical. Maybe now you’re thinking, “If we reject the suffering of the three realms of existence and avoid attraction to the quiescence of the hearers and solitary realizers, what is there for us to obtain? What we are to obtain is the state of bodhisattvahood, which is dependent on bodhicitta cultivated for the sake of self and others. It is only bodhicitta that leads beings from the suffering of existence to the state of fully enlightened buddhahood. We must avoid the two extremes: the quiescence of ordinary nirvana and the endless cycle of samsara. It is only through cultivating bodhicitta that we can truly follow the middle way.

Through cultivating bodhicitta you will purify all nonvirtue accumulated in the past, present, and future, and compassion and all noble qualities, including the ability to meditate in Samadhi, will blossom in your mind. As you dedicate yourself to the welfare of others, the [strength of your] vow will increase to the point where you are truly able to help sentient beings as limitless as space. You will be able to bring limitless beings to enlightenment, until the ocean of existence is emptied. The Buddha taught that without the cultivation of the precious bodhicitta, there is no chance to achieve the state of fully enlightened buddhahood. Therefore, for the purpose of all other living beings, with great enthusiastic joy you should give rise to the precious bodhicitta and engage in the actual practice.

Having adjusted your intention [in order] to begin the actual practice, supplicate the objects from which you will receive the vow. Recognizing the spiritual teacher to be the Buddha, first offer the mandala to receive the bodhisattva vow. Then repeat the supplication to the spiritual teacher and request to be a recipient suited to receive the vow and to accomplish the training for the benefit and welfare of all living beings.

Next, go for refuge in the sublime supports: the Buddha as the embodiment of the three kayas, the dharma as the representation of all scriptural transmissions and realization, and the Sangha as those who have attained the irreversible path of the sublime ones. From this moment until enlightenment, in order to liberate all parent sentient beings from their suffering, develop compassion. Realize that [in order] to accomplish your goal, aside from reliance on the Three Jewels of Refuge, there is no other support for refuge. It would be impossible for you to bring all beings to liberation without the buddha, dharma, and sangha. With irreversible faith and devotion, repeat the vows of refuge.

According to the Mahayana path, we take refuge in the teacher who shows us the path to liberation: that is the buddha. We engage on the path of Mahayana practice by cultivating the precious bodhicitta until we realize buddhahood: that is the dharma. The sangha is the spiritual community that is on the same path as we are on, assisting in the accomplishment of our mutual goals.

Next is the method for accumulating merit. Visualize in the space in front a magnificent throne supported by eight lions, where your teacher sits, indivisible with Lord Buddha Shakyamuni. The eight arhats and a vast assembly of buddhas and bodhisattvas surround him like masses of clouds that fill the ten directions. Imagine countless emanations of yourself filling the entire pure realm of your environment, which includes the entire universe. You and countless emanations of yourself and all parent sentient beings join together to fill [all of] space. With humility, reverence, and faith, you and they all bow down and pay homage to the objects of refuge in the space in front. [Here you] prostrate by touching the five places of your body to the ground. This is the branch of prostration, a powerful antidote for pride. Having pride means having the attitude of cherishing yourself by thinking you are so great and special. Performing prostrations purifies that egotistic attitude.

Now visualize that you and innumerable emanations of yourself present boundless offerings. Offer all of your wealth and endowments, including the root of all virtue in this lifetime, in all your past lifetimes, and in future lifetimes. Offer objects that are of this world and those that are transcendent. Imagine them to be inconceivable vast clouds of outer, inner, and secret offerings that completely fill space. In addition, offer the essential nature of reality.

The next branch involves [making] confession.

The next branch concerns rejoicing.

The next branch is that of requesting the buddhas to turn the dharma wheel.

Next is the branch of requesting the buddhas and bodhisattvas not to pass into nirvana.

The final branch of the seven entails the dedicating of merit. Amass all merit, especially the merit of reciting these seven, as well as all virtue and merit of the three times, and offer it for the welfare and liberation of all parent sentient beings. [The practice of] dedicating merit is the antidote for having many degrees or levels of doubt.

The second aspect related to the ritual is that of bestowing the vow, which has two parts: training the mind and receiving the vow. To train the mind, one begins by thinking of all parent sentient beings that have remained in cyclic existence from time immemorial until now and that have been extremely kind as one’s own parents in the past. Consider how they suffer unceasingly. Then think, “In order to alleviate the suffering of all these beings, I will give myself, my life, my wealth, and my endowments, and without ever giving up, I will work unceasingly to free sentient beings from suffering. I will happily take upon myself whatever suffering they are enduring.”

The actual bestowal of the vow follows.

Begin the stages of training by establishing the three moralities. The first morality, which is the basic morality of bodhisattva training, is to abstain from harming others. The second morality is to practice to amass great virtue, which means constantly practicing the six paramitas of generosity, morality, patience, diligence, meditation, and the wisdom of knowing the nature of emptiness. The third morality is to accomplish the purpose of others, which means directing all effort and actions toward the sole purpose of repaying the kindness of parent sentient beings and establishing them in the state of fully perfected buddhahood. Keeping all this in mind, you take the vow.

When you recite the verses of the vow, you should be in the state of the three recognitions. The first recognition is to have strong faith and devotion in the gurus, buddhas, and bodhisattvas because of knowing their noble qualities. The buddhas and bodhisattvas possess omniscient knowledge concerning the details of the relative lives of all sentient beings. Not an instant goes by where they do not simultaneously know the nature of all phenomena. The second recognition is to have tremendous compassion for all parent sentient beings, to feel completely responsible for repaying their kindness, based on all the reasons explained earlier. The third recognition is to work unceasingly and tirelessly to establish all parent sentient beings in the state of fully perfected buddhahood.

To take the vow, kneel, press your palms together, and feel certain that the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions abide in the space in front of you. Give rise to the three recognitions. With strong, fervent regard and the aspiration to accomplish your vow, recite the verses of the vow. When you complete the third recitation, feel certain that you have received the bodhisattva vow.

Upon receiving the vow, you should rejoice. Consider that you have taken countless rebirths with innumerable bodies, and that not until now, in this present rebirth, have you had the opportunity to really cultivate the enlightened mind with the vow to guide all beings to liberation. With that in mind, rejoice in taking this vow, and feel you have finally extracted the purpose of your human life.

The following are the concluding stages of dedication [the third and final aspect of the ritual itself]: To begin, consider the benefits of taking the bodhisattva vow. Although the benefits are so vast they cannot be enumerated, a few of them will be mentioned here. When cultivating bodhicitta and taking the bodhisattva vow, you are elevated from the rank of an ordinary individual to become a son or a daughter of the bodhisattvas. Now you are an object of homage for gods and ordinary human beings.

Even though you [may] lose mindfulness, if you never lose the bodhisattva vow, the force of bodhicitta will always bring you back to your original vow. The more you become accustomed to the bodhisattva vow, [the more] your negative tendencies and habits will be transformed and absorbed into the continuum of bodhisattva training.

The four stages involved in receiving the bodhisattva vow include receiving the vow, maintaining the vow, practicing the six paramitas, and achieving equanimity, which means purifying the mind from partiality or attachment and aversion. With these four stages [complete], the noble qualities and benefits are ineffable.

These few points provide a very brief, highly synthesized enumeration of the benefits of the bodhisattva vow, benefits that are otherwise inconceivable and inexpressible. If we tried to express any form these benefits could be likened to, even the sky would be unable to contain that.

Keeping all that in mind, recite the verses of rejoicing in your personal good fortune, followed by the verses of others rejoicing with you. Invite all beings to be present, including all the buddhas and bodhisattvas, and ask them to bear witness as your guests on this occasion of receiving the bodhisattva vow. As you recite the verses, think that all beings rejoice along with you.

Once you receive the vow, you must know how to guard it from deteriorating. This brings us to the teaching on how to ensure that the vow does not degenerate, which involves the three things to know—namely, how to keep the vow, how to train, and how to stop external forces and circumstances that may hinder you in your ability to keep the vow.

First, the instruction on how to keep the vow concerns the cultivation of aspirational bodhicitta and the training in practical bodhicitta.

The second part concerning how to keep the vow involves the training in practical bodhicitta. Here you must reject the two categories of downfalls, which are the root and branch downfalls. Those are downfalls that can occur within the context of the various categories of vows one takes. For example, there are five root downfalls that pertain to rulers, five to ministers, and five to beginners. There are also vows for those who practice on a common level. Any individual who has taken the bodhisattva vow is capable of committing a downfall. However, these instructions do not pertain to any individuals who had a mental impairment or deficiency or were unconscious and therefore didn’t know what they were doing when they took the vow.

Next is the discussion on how to repair the vow if it degenerates and how to continuously cultivate and maintain the vow. [This is the third of the four main aspects related to receiving the vow.] The three ways that a vow deteriorates are by losing the foundation for the aspirational mind, through rejecting the vows by returning them, and by allowing a root downfall to occur. In the first and second cases, the vow is completely lost and must be taken again in order to be restored. In the third case, if you commit a root downfall, you must confess it immediately. If you postpone [your] confession of a downfall, that downfall will become more and more difficult to purify. Apply the four powers, and in the presence of the Three Jewels of refuge, confess your downfall. Pray to purify any negativity accumulated through the downfall, and then perform purification practices.

Once you have received the bodhisattva vow, you may take it again either if you have lost it or [in order] to ensure that it does not diminish. To retake the vow on your own, consider that you are in the presence of the buddhas and bodhisattvas. With strong faith and devotion, feeling they are present, take the bodhisattva vow directly from them. Otherwise, you can use a support of the Buddha, such as a statue for enlightened form, a scripture for enlightened speech, or a stupa for enlightened mind. If you do not have any of these supports, you can use the power of your own mind in order to take the vow.

The reason we retake the bodhisattva vow is because we are habituated with the five passions. We always do the opposite of what should be done. We always turn things into negativity. The little bud of our buddha nature, which is just beginning to open, should blossom when exposed to the blessings of the sun and the refreshing showers of dharma. Instead, it dries and closes due to [our] negative habits that obscure the circumstantial blessings that come through the dharma. If we encourage ourselves by continuously reaffirming pure intentions and by taking the bodhisattva vow over and over again, that will give us the power and strength to rise up despite all the difficulties imposed by the influence of our passions. Then, by focusing on the vow and training, we will obtain the confidence to abandon self-concerned fixations. Emphasis shifts from the self to the needs of others. Once our bodhisattva vows become strong, accomplishing whatever prayers or aspirations we hold in our hearts will be very easy.

The three dharmas to adopt are to rely on a spiritual teacher, to make offerings to the Three Jewels, and to never abandon compassion for any sentient being. The first of the four recognitions to accept is to examine yourself to see whether you have the potential to uphold the vow and to maintain the training. The second is to examine to see whether an action is virtuous or not. If you determine it to be virtuous and fail to accomplish it, or if you contradict it or remain indifferent, then in all three of these cases there will be a downfall.

[Third,] in order to constantly guard the vow, you must be learned in the teachings on bodhisattva practice as found in the scriptures, particularly those [teachings] that discuss the subject of cultivating bodhicitta. [Fourth,] you must know how to be conscientious and mindful, so that [your] bodhisattva training will not deteriorate. If your training is free from deterioration, that indicates you are practicing mindfulness.

Although there are countless ways of knowing how to guard the vow to ensure that it will not be lost, they can be synthesized into three. First, the bodhisattva training must be internalized as much as possible. Second, the internal training must be expressed externally to meet the needs of beings by bringing them the gift of dharma. Finally, there must be the pure view of the pure lands of the buddhas. From now on, at all times and in all situations, with loving-kindness and compassion, you must do your best to always be of benefit to all sentient beings equally. No matter what, you must never abandon any living being for any reason. In addition, you must never be biased towards some and against others. From this time forward you must consider all beings impartially and with loving-kindness and compassion, and you must do your best to always increase your virtuous deeds, which you dedicate to the service and benefit of others. This is how you will be able to keep your bodhisattva vow.

It is especially important to always cultivate mindfulness. Once you have taken the bodhisattva vow, if you are mindful of it, then you won’t forget to direct your every effort toward the practice of dharma. It is also important to cultivate conscientiousness, which will stabilize your ability to be mindful. Finally, it is important to be careful in all the different circumstances of life. Mindfulness, conscientiousness, and care are extremely important.

[Once you have taken it] you will have the bodhisattva vow in your mind. You will no longer be an ordinary world individual, as you will have entered the path of the bodhisattvas to become a son or daughter of the buddhas. If you keep your bodhisattva vow, without allowing it to degenerate, then you are truly a bodhisattva. If you drink a cup of water from the ocean, you can say that you drank the ocean; likewise, if you enter the path of the bodhisattvas, you can say that you are a bodhisattva. With faith and devotion, please do your best to keep this vow.

[1] [While the word in the term bodhisattva vow is commonly used in its singular form, it is also often used in its plural form, bodhisattva vows. Both the singular and plural forms of the term in fact represent a series of vows. Readers will find both forms used throughout the commentary.—Ed.]

From “THE PATH of the Bodhisattva: A Collection of the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva and Related Prayers” with a commentary by Kyabje Pema Norbu Rinpoche on the Prayer for Excellent Conduct

Compiled under the direction of Venerable Gyatrul Rinpoche Vimala Publishing 2008

[Adapted from an oral commentary given by His Holiness Penor Rinpoche in conjunction with a ceremony wherein he bestowed the bodhisattva vow upon a gathering of disciples at Namdroling in Bozeman, Montana, November 1999. —Ed.]

General offerings please the senses. Imagine those offerings to be vast and inconceivable. However, if you were to [attempt to] compare the outer offerings with a single particle of the realms of buddhas and the quality of offerings made in the minds of enlightened ones, [you would find that comparison] to be beyond the scope of your imagination. That is why it is so important while presenting offerings to try to connect with the ultimate nature of offering, which is mental and not just material. Material offerings you make are supports for your mental or imagined offerings, which should be as inconceivably vast and wondrous as you are capable of manifesting. The actual offerings you use as a support should also be the best substances you are able to offer. At least they must not be old, dirty, or leftover substances; they must be suitable supports for the basis of virtue. The pure material offerings you make will be the support for the continual manifestation of inexhaustible offerings that will remain until samsara is emptied.

There is a well-known story of an accomplished practitioner named Jowo Ben. One day Jowo Ben made a very beautiful, clean, and pure offering on his altar. As he sat and looked at his offering, he thought, “What is it that makes this offering I’ve made here today excellent?” Then he remembered his sponsor was coming to visit that day, and he realized he had made the beautiful offering in order to impress his sponsor. He jumped up, picked up a handful of dirt, and threw it on the altar, saying he should give up all attachment and fixation on worldly concerns. Other lamas, on hearing what Jowo Ben had done, proclaimed his offering of throwing dirt on his altar to have been the purest of offerings, because Jowo Ben had finally cleared his mind of attachment and aversion.

When offerings are made, they are rendered pure and excellent by a mind free from attachment and aversion to the ordinary, material aspect of the offerings—and they must be made with a mind that is also free from avarice. Don’t think you can throw dirt on your altar and think that will benefit you. You must adjust your mind. If your mind is free from attachment or fixation and aversion, then whatever you do will be right. If your mind is not adjusted and your intentions are impure, then no matter how beautiful and magnificent the offering is, it will be insignificant. If you present all offerings, whether abundant or meager, with fervent devotion from the core of your heart, that will produce profoundly amazing results.

In order to be free from the suffering of existence, the mind must be free from dualistic fixation. In freedom from duality, everything is inherently pure. Just imagine all the wonderful offerings that are made that are free from duality: pure water possessing the eight qualities, garlands of flowers, incense, light, superior perfume, celestial food, musical instruments, fine garments, beautiful umbrellas, canopies, victory banners, the sun, the moon—the finest and best of everything is offered. Consider those as offerings arranged in a magnificent array equal in size to Mt. Meru. Furthermore, know that those offerings are pure and free from duality. For example, if you were to pick a flower and think, “Oh, this is such a beautiful flower; I want to offer it,” but then you also think, “My flower is more beautiful than the others,” and you offer it with that dualistic thought, then that offering would be defiled by your dualistic fixation. On the other hand, if you focus on the pure nature of the offerings and present them with pure devotion, you will make offerings that are pure or free from dualistic fixation. Recite the verses of the branch for offering, and make the most excellent, immeasurable offering you are capable of with the enlightened attitude [bodhicitta], faith, and pure devotion.

It is important to understand that presenting offerings is the antidote for [having] desire. Offerings are not made to the Three Jewels because they are considered to be poverty-stricken and in need of receiving from their disciples; offerings are made to accumulate merit. By making offerings with actual material substances, we accumulate ordinary conceptual merit; by using the mind to manifest immeasurable offerings, we accumulate nonconceptual wisdom merit.

From “THE PATH of the Bodhisattva: A Collection of the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva and Related Prayers” with a commentary by Kyabje Pema Norbu Rinpoche on the Prayer for Excellent Conduct

Compiled under the direction of Venerable Gyatrul Rinpoche Vimala Publishing 2008

Being grateful for the many gifts I have been endowed with in this very lifetime, I now wish to offer a prayer usually associated with vows:

Today I have picked the fruit of this lifetime. The meaning of this human existence is now realized. Today I am born into the family of buddhas and have become an heir of the enlightened ones!

Now, no matter what occurs hereafter, my activities will be in conscientious accord with the family, and I shall never engage in conduct that could possibly sully this faultless family! Like a blind man in a heap of refuse, suddenly by chance finding a precious jewel, similarly this occasion is such that today I have given rise to the awakened mind!

Today, before all of my objects of refuge, the sugatas as well as all beings, I call to bear witness where the guests of this occasion- the devas, Titans and others- all join together to rejoice! The precious Bodhicitta, if unborn, may it arise; when generated may it never diminish and may it always remain ever-increasing!

Never apart from Bodhicitta, engaged in the conduct of the awakened ones, being held fast by all of the buddhas, may all demonic activities be fully abandoned!

May all the bodhisattvas accomplish the welfare of others, according to their wisdom mind’s intentions.

Whatever wisdom intention these protectors may have, may it come to pass for all sentient beings.

May all sentient beings be endowed with bliss, may the lower realms be permanently emptied! May all the bodhisattvas, on whatever bhumi they remain, fully accomplish all of their aspirations!

From “THE PATH of the Bodhisattva: A Collection of the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva and Related Prayers” With a commentary by Kyabje Pema Norbu Rinpoche on the Prayer for Excellent Conduct

Compiled under the direction of Venerable Gyatrul Rinpoche Vimala Publishing 2008

I find that prayer soothing, comforting, and dedicate it to all who are suffering in any way. May all beings benefit!

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love Series

One of the problems that we Westerners have is that we’ve grown up with religions that say God is external. That is not what the Buddha teaches. The Buddha teaches us not that our supreme object of refuge is an external God, but that ultimately, in the deepest sense, our supreme refuge is enlightenment, the uncontrived natural state free of desire. According to the Buddha’s teaching, it is possible to achieve realization; that desire-free state, that natural uncontrived wisdom state is attainable. According to which path you take, it is attainable in many lifetimes, it is attainable in some lifetimes, it is attainable in a few lifetimes, or according to the Vajrayana, with sincere practice it is attainable in one lifetime.

You have to decide for yourself what you’re going to do. It’s a difficult job, because we are so filled with ideas from our upbringing. People say, “I’m moved by what you say, but I just don’t know if I can renounce everything. I just don’t know if I can give everything up.” That’s not what’s being talked about here. What’s being talked about is that you have to determine your objects of refuge. You have to determine what your refuge is, and from that you should make your own decisions. There are many different levels at which you can practice. You can become a full renunciate, taking vows, taking robes. You can also practice in a more casual way, laying the pathway for eventual deeper practice. Nobody’s making a rule for you. The point is that you should think for yourself and you should think past the ways in which you were brought up. You should look courageously at suffering, at the causes for suffering, and at the end of suffering.

According to the Buddha’s teaching, there is nothing on this Earth that can end suffering for all sentient beings. If we found the cure for cancer, AIDS, for everything, something else would happen, because the karma of sickness is there. If we found the cure for poverty, something else would happen. If we found the cure for war…. and all these ifs are mighty big. The karma of suffering is desire. It is the root cause for all suffering. Having determined that, we have to think that to get rid of it from our mindstreams will take something more profound than manipulating our external environment. The problem cannot be solved in that way.

I think it behooves us as Westerners to think deeply about these things. From my point of view, I have seen Westerners adapt the Buddhist religion, and I am not satisfied in the way that they are doing it. They’re practicing Buddhists, they know the mudras, they know the mantras, and they know how to ring the bells. They know how to do all the ceremonial things that come with the Buddhadharma; and I am not happy with their minds. Because maybe they didn’t take long enough to decide for themselves what the object of refuge is and what the cause of suffering is.

You can collect Dharma in a materialistic way just as well as you can collect cars and TVs. You can collect Lamas and the blessings of Lamas in a materialistic way just as easily as you can do anything else. You can collect new thoughts and new ideas and spiritual truths and books and all kinds of things, and never change. Or you can come from a really pure place and examine these things with courage and with pure intention. You can be determined to awaken the seed and the fire of compassion in your mind by examining the suffering of all sentient beings. You can encourage that flame, that fire, fanning it into life so that it burns away all obstacles to your practice. And you’ll find for yourself your object of refuge, and you’ll go…just go. You can do that. It takes courage and it takes pure intention and it takes determination to really think about these things, in a logical and real way. That’s what I hope you will do.

I am a Buddhist, and I always will be. But I’m not trying to sell Buddhism. What I would like to see is a world without suffering. That is the point, hopefully, of all religions; certainly of mine. I wish to talk about the same thing Lord Buddha himself talked about: the causes of suffering and the end of suffering. If we start there, thinking of these things and thinking of them with what Buddhists call fervent regard, we can make a lot of progress.

Contemplating these things creates a great deal of virtue and merit. After you think about these things, please dedicate the time that you spent and the effort that you took, to benefit all sentient beings. In other words, offer the virtue or the merit that you have accomplished by even just wanting to love. There’s a tremendous amount of virtue in that. Offer that as food and drink to all sentient beings so that the karma of that can be shared with a world that is suffering.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved