The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

Now, let’s look at the bardo of the moment of death. Our body is made up of four elements: They are the earth element, the water element, the fire element, and the air element. At the moment of death, and what death actually is from a metaphysical point of view, these elements begin to disengage. Here they are knit, you see, into a fabric. They are knit into what you think of as yourself.

I will explain. Flesh, the bones, and the solid constituents belong to the earth element. They are considered the manifestations of the earth element, and you can see that these are part of your body system. Blood, phlegm—which we have more of in the wintertime, isn’t that true—blood, phlegm and bodily fluids belong to the water element, and you know you have those, especially in the morning. Body temperature, metabolism, the raising of your body temperature to be warm, belongs to the fire element,. And you know that that is within your body, you can tell that you are warm. And respiration belongs to the air element.

What happens at the time of the death is that these elements begin to dissolve in their interconnectedness. They dissolve into their natural state, and their natural state, of course, separate and apart from our deluded perceptions, is the same as one’s own nature. It is the Buddha. In their natural state they are none other than the Buddha. Yet we experience them as fire, earth, air, water. We are taught in our practice to recognize them, because they will appear, even in the bardo state, disguised as the goddesses of fire, earth, air and water. And we still won’t recognize them. We still won’t recognize them. We won’t recognize anything in the bardo state unless we prepare for it and think ahead. But in fact, in their very nature, although we are afraid of them and afraid of the very feelings that we are feeling, when these elements begin to dissolve, still in all, these are also the Buddha. And even recognizing these elements in their nature is one step toward the path of liberation. So do not be afraid.

At the moment of death, the elements are absorbed into each other giving rise to a twin series of phenomena, both internal and external. I love the way this lama [Bokar Rinpoche] has put this, and so I’m going to utilize this and then I will elaborate. These are the conditions that indicate the actual moment of death, the passing into the bardo of death. First, the earth element is absorbed into the water element. How that is experienced externally is that the limbs can no longer be moved. And how that is experienced internally is that the mind begins to see things like mirages. That is the earth element absorbing into the water element. Then, the next stage is that the water element is absorbed into the fire element. Externally, that experience will be of the mouth and the tongue becoming quite dry. (I must be dying because I’m dry all year; it’s one of the signs. My limbs are moving, though! I’m really glad about that!) So externally, the mouth and tongue become dry, and internally we perceive smoke that passes us or rises up before us. You should take note of this. These are the experiences that you must rehearse seeing, because you will see them. Know them, rehearse them, prepare for them, expect them, and recognize them in their nature when you do. Do not be afraid, there’s nothing to fear. So we perceive smoke that passes us or rises up.

Next, the fire element is absorbed into the air element. Externally, heat leaves the limbs, moving from the extremities toward the center of the body. This is seen in a hospital environment when people die. They do actually have that progressive coolness that comes from the extremities into the center of the body. Internally, we will be seeing an array of sparks. An array of sparks. And then finally, the air element is absorbed into the individual consciousness. There’s a footnote here, and I’ll sum it up. Here, when he says ‘consciousness,’ he wants us to know that he’s referring to the consciousness that operated in a dual mode—grasping an object that is separated from a subject. That kind of mind of duality. So he’s talking about consciousness in the familiar way that we use it now. So finally the air element is absorbed into the individual consciousness. The external breath actually ceases. Internally, what we will see is something like the flames of flickering butter lamps. Flickers. Flickers. That will be the air element actually absorbing into our own consciousness.

Now here are some additional bits of information that I would like to add as a way of recognition. Here are some other signs that actually occur. This sign is associated with the earth element. The first dissolution is the earth element absorbing into the water element. a During this wave of dissolution of the elements, one of the experiences that we will feel— and we will all feel this—is the feeling of falling. A lack of safety. There is a feeling of falling. It depends on how the person is. If a person is semiconscious or unconscious they may actually feel themselves falling down a tube, or even falling across a tube. But there is a feeling of falling. For many people, and I would say the majority of people would feel this way, there is actually a feeling of the body falling and not being safe. You can help a person who is dying by placing pillows around them to make them feel as safe as possible and creating a nest, womb-like nest, even under the knees, even under the armpits, even under the arms, around the body, so that until the very last moment of their perceptual capacity they will still be able to feel nested, as though they are safe. Then when the other feelings are obviously beginning to occur you can begin to explain to the person. You can say things soothingly like, “Pay no attention to the feeling of falling. You are safe. You are not falling. You are with me.” That kind of thing. You can talk and it will help them.

The person who has had time to prepare will recognize the feel of falling and will be able to interpret it differently as perhaps a feeling of going, which does not have to have the fear of falling associated with it. You wonder if that feeling is actually going to come to you. Okay, have you ever fallen asleep and jumped? It’s the very same thing. There is the subtle dissolution of the elements as one enters into the dream bardo. That is similar to the death, but not as gross and heavy and final. So there’s the feeling of falling, and sometimes the person who is dying will do that a little bit. That is how you can tell that that is actually occurring.

When they talk about the mouth and tongue becoming dry, I’ve also heard that sometimes the person, right before death, will actually void what is in their body, or right at the time of death will actually void what’s in their body. That is also an indication that this has begun to take place—that the water element is now absorbing into the fire element. And so you will see signs like that. Here, even in enlightened death—we’re talking about Kalu Rinpoche’s death—he needed to, he wished, he had the intention, the feeling, to get up and void himself, and prepare himself in that way. But that is an indication that the elements are already beginning to dissolve.

And of course, the feeling of cold, the feeling of the heat leaving the limbs. It is absolutely beneficial to the person as they are dying that you keep them as warm as possible, because their comfort during that transition time is very important. It will influence the way their mind accepts the experience. So keep them warm to the best of your ability. If before the death cycle actually occurs you could do something like what they would do in the old days, put a warm brick at their feet, put something warm at their hands, comforting, this is the time when you want to help the person keep their mind as comforted and relaxed as possible. So you do everything you can to help those feelings not to be so scary. And these are things that you can tell the ones around you to help you prepare for death, should you be the one experiencing this transition.

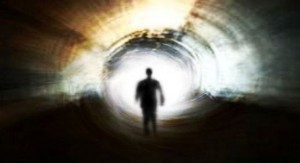

Finally, the air element is absorbed into the individual consciousness, as we spoke of, and that’s when the breathing stops. Now when the external breathing stops that does not mean that death has actually occurred, even though medically that’s what they look for. They look for the cessation of the breath. There’s actually a period of time during which, again, depending on the practice or the understanding or the inclination or the habitual tendency of each individual person, experience continues. When the outer breath stops, already visions have begun to arise, already images have begun to happen. There are lights, there are colors. There are things occurring that are unusual. There are visual things coming up. But the time in which we are actually considered dead, really dead, is after the external breath has stopped. And the other period of time, that is a very essential and crucial period of time, also passes. And that is the time between the stopping of the outer breath and the stopping of the inner winds. We have within us the air element. Its most gross display is our breath. Yet there’s more to it than that, because within us are psychic winds and channels that are not see-able by fleshy eyes. Yet they still exist.

These psychic winds and channels have much to do with the condition of our minds. That is to say, if our minds are disturbed and neurotic and needy and always upset, that kind of mind, the winds that move within the psychic channels of that mind will be erratic. Like ‘puh, puh, puh, puh, puh,’ rather than ‘whoooooooooooo,’ kind of like that. They will be erratic. The wind channels, the channels within, will be soiled and dirty, and sometimes misshapen and kinked. And so the inner experience then will be different for that kind of person than it is for a person who, say, has practiced and has kept their mind very kind and happy. The calmer and happy mind will have the inner winds moving through the psychic channels more calmly and serenely. Then when they stop, it will be a more calm and serene kind of experience. Also, that small moment of experience when only the inner winds are still operational and the outer breath has already ceased will be much different as well. That inner experience will be much different. So by all means, do not think that it’s goofy to try to keep yourself up and happy and peaceful and in a good mood. That’s not goofy, that’s great. That’s what you should do. It really is beneficial to you. It really produces health, and you will live longer. You will definitely live longer if you can keep yourself up and happy and in good humor, peaceful in your mind. You will live longer.

At the end, there is a period of time between when the outer breath stops and the inner winds also cease. That, for the practitioner, is the most important period of time. The practitioner who has practiced Phowa will be very busy right then. The person who is helping the dying one through that particular period must know this: Once the outer breath has ceased, do not touch the body except at the very top of the head, right here [the crown]. This is so important. Please, try to understand how important this is. I cannot emphasize it enough. Make arrangements for yourself; make arrangements for your loved ones. Write it down so that nobody screws it up. This is important, and here’s the reason why: Just as it is possible for each of us to go to any of those six realms of cyclic existence during the bardo of becoming, there is also an apparent method or exit point by which we go into those six realms. For the lowest hell realms, it is through the anus. That is literally how we go into those lowest realms. For the secondary low realms, it is through the genital channels. The consciousness will actually leave the body through those channels, and that will absolutely write in stone and dictate the next experience. One can leave through the nostrils; one can leave through the mouth; one can leave through the ears. One can leave in many different ways. But the way to leave in order to achieve rebirth in the pureland is to leave correctly through the central channel out the top of the head. And we will get into how to do that. We will teach you how to do that. And we will prepare you for that, so that the channel is nice and clean and it’s easy to get out.

If you’re with somebody who’s dying, and if you touch them… A lot of times loved ones will make the mistake of holding a hand or patting a person on the thigh. What happens is that—the outer breath is already stopped, you see—inside, their cognition is very loose and fluid, very loose and fluid, and influenced by everything. That’s why you want to have their pillows nice. If you are a practitioner, if it’s possible, it’s best to be sitting up in the meditative posture, propped up with pillows if you can’t quite manage it. It’s best to be in that position because it is the best position for a peaceful mind. It is absolutely the best position for a peaceful mind. If a person around you makes the mistake of touching the wrong part of your body when you’re in that highly suggestive and fluid state, the person dying may leave through the wrong exit, literally. Just that little condition can be very troublesome. And so, do not draw the person’s attention to any place else other than the very top of their head right there. In fact, if you can, as the person’s outer breath ceases and their inner breath is still going, you may take a little bit of the hair right there [top of head] and tug. Internally, the person’s attention will go up that way and their consciousness will follow. Even if they’ve done no practice, it will help. Or you can rub, or you can tap. Again, set it up so that someone will help you with this when the time comes. Or so that you can help others when the time comes. That point is a very important point.

The things that are happening to us we’ll have to learn a little bit later. I’m sorry about that. I really need to get all of this out. We have too much to do this week, but this is fascinating stuff. You’ll be interested in this.

After the outer breath has ceased and the inner winds are beginning to die down and are now in the process of cessation, these are the inner images that will be experienced by all of us. How we experience them may vary, but if you learn to recognize them in this form you will recognize them in any form that is particular to your characteristic form of perception. So there will be variations in your own individual experience, but again, practicing and hearing this teaching, you will understand. You will get the lay of the land, and you will be ready.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved