The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “The Lama Never Leaves”

Today, I would like to talk about what we have here. Not only the objects of support that I’ve talked about, but we have the stupas. I would like to explain to you the nature of the stupas. I would like to explain to you a little bit about the treasures that we have here. To say that there is nothing like this in America sounds prideful. Yet, I am not the one saying it, really. I’m telling you what other teachers who have come here and who have been around America have said—that there’s nothing else like this, that this is quite remarkable. And I say, “Well, we’re just getting started. I hope it’s good.” We have here these extraordinary stupas that have been built according to the ancient Palyul tradition by a number of lamas—His Holiness, and then Tulka Rigzin Pema Rinpoche who is a renowned stupa builder. The stupas have been blessed by every lama that has come here; but they have been properly consecrated, about that there is no doubt.

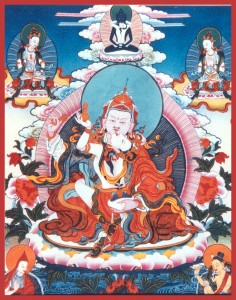

The stupas have different levels and ultimately when they are born, that is to say, after they are completely built and the lama actually generates the entire mandala of the deities and all the objects of refuge, , and descends that entire mandala into the stupa, the stupa becomes then a living presence. The stupa becomes like the Buddha in Nirmanakaya form, that is to say in the physical form.

On the bottom of the Stupa, there are many objects there that indicate the things of the world to be overcome, such as objects of violence like knives and guns and weapons, and they are buried underneath. There are prayers and objects and images of suppression, including symbols of death, that go on top of that and they suppress the things of the world that are harmful., At the time of the filling of the Enlightenment Stupa, His Holiness said, “Well, it would be good if we had the skull of a wolf to put down underneath there.” I went, “The skull of a wolf? In Maryland???” So we were rushing around thinking, “How in the world does one get the skull of a wolf?” trying to figure it out. And then we had the great good fortune, I guess… A fox up the road got run over and we had an intact fox skull. So we brought the poor little fox skull to His Holiness and said, “Would this do?” And he went, “This is pathetic. Look how small it is. Well, if that’s what you call wolf in America, this will have to do!” So it turns out, the fox gets in there asthe symbol of death. We have symbols of old age, of sickness, of death, of all kinds of suffering, and the suppression of that.

Above that, there are different layers. There are the practices: beginning stage practice, generation stage practice, completion stage practice, accomplishment. Then there are the objects and prayers and mantras that are associated with all these different levels wrapped in a very succinct way, arranged perfectly like the mandala of the deities. It has to be arranged very perfectly, and it’s all very secret and careful. Nobody can look in there unless they’ve been on the stupa diet, which is no animal flesh, no alcohol, no sexual activity and no ordinary stuff of any kind while you’re building the stupa. And the many many gizillions—I don’t even know how many—of mantras , with saffron water sprayed on them that are rolled so tight, some done by machine, because we could get them rolled tighter, and some of them done by students who themselves were reciting mantra at the same time they were rolling them very tightly and sticking to the stupa diet. So everything very carefully arranged, everything very perfect. You can’t leave a drop of sweat or a bit of DNA in the stupa unless you have achieved enlightenment. So nobody gets to really climb in there without being clothed up and very very careful.

When the lama then brings the stupa to fruition, there is of course the vestibule in which the deity sits, and the deity itself is completely consecrated like the deities on the altar, and they themselves have all the accomplishment figures in them. And then the relics are at the top. Some of them are wrapped up to the spine, that is a very large piece of wood with mantra written all over it going down the middle. Some of them are wrapped body, speech, and mind mantras of enlightenment. So then when the lama descends the deities into the stupa, the stupa is completely able to receive every blessing that the lama is capable of conferring. All the materials are blessed, purified and perfect. All the needs have been met.

The lama that actually empowers the stupa is always a lama of accomplishment. That is to say, Tulku Rigzin Pema Rinpoche is known as a stupa lama and maintains the stupa diet always. He maintains retreat a lot of the time in order to keep the stupa-related accomplishments fresh in his mind as though they were like fresh bread, just right there at the tip of his tongue or the tip of his mind—however you would put it—able to be conferred. Then of course His Holiness Penor Rinpoche who empowered the Enlightenment Stupa is a living Buddha and is known worldwide as a living Buddha. In Tibet, people gather the dirt that he walks on and save it and put it on their altars. His foot-print even. He never is not practicing. I’ve seen the way his mind works. He is like… Well, he is a living Buddha. There is no other thing to say about it.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved