An excerpt from the Mindfulness workshop given by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo in 1999

How does one practice the recognition of the empty nature of all phenomena? One of the ways that we can do that is by pacifying reactiveness through a deeper understanding and discrimination. Reactiveness is an inner enemy. In a very profound way, it’s probably your worst enemy. It is the seat, the throne, the source of all suffering. It is really our reaction to samsara and the resulting activity that that brings our suffering; that is our suffering. Like the Buddha said, our suffering is all based on our clinging to self-nature as being inherently real and the desire that arises from that. This reactiveness is truly the enemy. I can’t say that often enough.

Since time out of mind we have believed in self-nature as being inherently real. Since that first idea of self-nature as being inherently real, we have spent every moment from that point on securing ourselves, establishing ourselves, making ourselves safe and defining – most of all defining – ourselves. In order to define myself, I have to see you as separate. All of the ideas we have that come from that are truly samsaric in nature, even, as a practitioner, the idea that I should walk around looking very noble and very holy and very renounced. Even that idea, although it may seem to be about practicing on the path, is actually about the samsaric clinging to self-nature as inherently real.

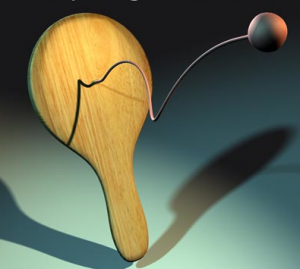

So this discrimination that we practice has to antidote that very thing. How are we going to antidote that very thing? That’s not so easy. Reactiveness, if you think about it, is a perception about self-nature being real, the perception of other, and the reaction is based on hope, fear or neutrality. As a human being, if I see you, I hope that you will make me happy. I hope that you will make me safe. Or, if I see you, maybe I fear that you’re going to be prettier than me or richer than me, or I fear that you’re going to be unkind to me or that you’re a danger to me. Neutrality comes after you go through both hope and fear and you’ve decided it’s pretty well balanced, so you’re neutral about this. Neutrality is not wisdom. When we have that kind of a reactive mentality, it is such a knee-jerk reaction that it is automatic. There is never a thought that says, “Oh boy, now I’m going to react to this.” When somebody walks in the room, you don’t think, “Now, watch me react.” When something happens to you, you don’t think, “Watch this.” I have the image of these old-time paddleballs with an elastic string and a ball on the end, you know? The only thing that you can do with it is bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam, you know, like that? Our minds are like that. We are like that, bam-bam-bam-bam-bam. The thing that’s happening is that we perceive ourselves as being real and solid; we perceive stuff as being “out there,” and the only thing it can do is hit us, and the only thing we can do is bounce at it, and it’s bam-bam-bam-bam-bam, reaction, reaction, reaction, reaction, reaction, because we cannot have a second where we don’t reinforce the idea that self-nature is inherently real. Maybe we would disappear. So bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam-bam! That’s what we have to do, and it has to be constant or maybe time won’t pass or things won’t be solid.

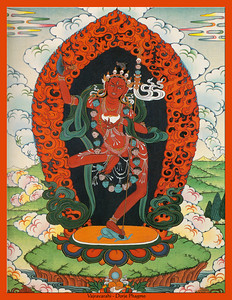

To apply the antidote to that, we are told to sit and practice and do the visualization. That is an antidote. The reason why it’s an antidote is because you’re not reacting to something that affects self-nature, but you are engaging in a visualization, giving rise to a deeper awareness of what your nature actually is. So it’s a great antidote for that. But if you really look at the phenomenon of bam-bam-bam and what it’s based on, you can see that there is no spaciousness between the idea of self-nature as being inherently real and BAM, the reaction. There’s no space. The mind can’t NOT snap back. Do you understand why I’m saying that?

To apply the antidote, you can’t just decide consciously not to react. That would only make you neurotic. That is the nature of the beast as we are now. You cannot pretend that you’re not reacting. You’d look holy, I guess, but it would make you a little weird. The way to practice is to try to get a little bit of space somewhere in the equation; to try to take a breath, give it a moment. How can you do that? I just said you can’t control that, so how are you supposed to do that? The way to do that is to begin to recognize the nature of the phenomena that you’re experiencing. When you go through this mental stuff and your mind is so tight and you’re bam-bam-bamming and you’re in that deeply reactive mode, you have the power to do this. Animals can’t do this, other kinds of beings can’t do this, but humans can do this. This is what’s unique about us. We can stand back, and we can say, “Oh yeah, that’s just like me. I do that.” Just that stepping back to observe phenomena without going crashing into it headlong in total ignorance and drunkenness and denial is an incredible practice. To be an observer just for a moment, to watch the equation – self-nature is inherently real, therefore…to watch the reactiveness, to watch the play that goes on there, begins to create some space in the mind. This is an incredible practice, and it should be done at times when you’re not deeply reactive.

To practice like that, you have to start very simply, when the mind is relatively quiet. Watch yourself looking at a tree. Watch how, when you look at the tree, the tree is only relevant if it makes you feel good. Otherwise, what do you care about trees? You couldn’t care less. But the tree is beautiful. It affects us. It’s very healing, pretty in the spring, shady in the summer, fruitful in the fall. Instead of being king or queen baby on your own little stage, perhaps you can observe yourself looking at a tree and watching how the tree is relevant as to how it affects you. Watch what happens when you watch the tree. When you look at the tree, just kind of watch that whole equation right then. At first, maybe it’ll happen too fast and you won’t be able to see it, but if you persist, you will get a wedge in there. Watch your mind.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo