An excerpt from the Mindfulness workshop given by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo in 1999

When we view one another, if we have taken teachings together or empowerments under the same teacher, we are Vajra brothers and sisters. We are family. When we see each other, we should be willing to lay down our lives for each other because there is nothing more precious than someone who is holding empowerment, holding the blessings of the Buddha in the world. That doesn’t mean you have to make a big display about it. You still have that one vertebra bow trick you could do. We hold our Vajra family as being most precious. We should think very, very carefully how we deal with our Vajra brothers and sisters. If we’re ill-tempered, hateful, scornful towards them; if we are not holding them in pure View, holding them as gods and goddesses, as deities and consorts, if we are not looking at them in that way, we are committing a non-virtue. If we speak with hatred or ugliness to a monk or nun, we are committing a heinous non-virtue. I don’t think it’s written “heinous” in the book, but I’m telling you, it is. It is a serious non-virtue because monks and nuns are the providers, the holders, of the doctrine that make it possible for us to practice. So if we were to speak with disrespect to a monk or nun, the one who suffers from that is us. The monk or nun, they’re going to react or not react. That’s their business. Whatever they do, that’s their practice. You’re only responsible for your own practice. And whether that’s a good monk or a good nun, that’s also not your problem. That they are holding the Buddha’s teachings invites you to accomplish pure View regarding them. So we should not think of monks and nuns as being equal to us. I think of monks and nuns as being higher. They hold the Doctrine, and I hold the view about them. So even though I am required, to sit higher than the monks and nuns, if I didn’t have this job, I would never willingly do it, never. I would never willingly do it. I know you guys on chairs, you’re thinking, “Oh God!” But in general, I will tell you that when you have the opportunity to sit lower than a monk or nun, you should try to do so, always. If you have the opportunity to receive a cup of tea from a monk or nun, receive it properly. This is from a monk or a nun! This is really important to hold the View. These nuns are goddesses. They are Tara, none other. These monks are the appearance of Avalokiteshvara in the world, Chenrezig. Their compassion establishes the Lineage on this Earth. It’s because of their efforts that we are able to keep ourselves together. It’s about raising up what is extraordinary, raising the Dharma up higher.

For monks and nuns, there is a particular hierarchy that we think of when we honor one another. For instance, the younger – I don’t mean younger in terms of age but younger in terms of ordination – the more recently ordained monks and nuns are supposed to hold the elders in higher respect, and you should because they have held the robes longer. Even if you’re better at your practice, if there is a monk or a nun that has held their robes longer than you, you hold them up. You practice that View. You monks and nuns that have had your robes for a long time, however, you don’t hold yourselves up. You don’t think, “Well, you know, I’m an older monk, I’m an older nun.” In fact, your job should be a little bit like the tactic I take. Perhaps you can allow younger monks and nuns to show some respect if that is their practice and they are willing to do so, but in your mind, you should be thinking, “These are the most precious ones, the babies, the newly ordained, fresh, moist with longing.” You should think that they are still fresh from that devotion, from that opening, from that pouring out and the gathering of merit that it took for them to become monks and nuns. You should think, “These are the jewels. I, as an older monk or nun, am responsible for bringing these along because they are so precious.” not because they are younger in their ordination. Do you understand that?

In a way, each of us is looking for ways to not have our own ego in the center of our own mandala. We are looking for a way to practice View so that we really begin to awaken to the sense of all phenomena, all appearance, as being none other than the celestial palace mandala, and that doesn’t mean thinking it. It means practicing like I said, not just saying, “Oh, everything is love and light, everything is celestial palace mandala.” That’s not how it’s done. That will produce absolutely zero result. Positive thinking is not the same thing as practicing View. Positive thinking is nice, it’s lovely, I hope you do it, but that ain’t what the Buddha taught. Practicing View is much firmer than that, and yet more subtle.

Practicing View is instituting the habit in your mind to see things differently than you did before. Practicing View is using every opportunity to get yourself, your ego, off that throne, and using every opportunity to flush out that obsessive-compulsive desire syndrome. You know that syndrome: the one that says if you have something sweet, now you have to balance it with something salty and then you have to have something sour and then you have to something wet and then you’re thirsty and then you’re hungry. That is never ending. Those are the attributes of your ego. That is what your ego does, that obsessive-compulsive nature, that constantly going around in circles with what we want. That is absolutely the nature of the ego. That is all it does. That’s all it does, and your five senses help you do it. You smell what you want, you see what you want, you touch what you want, you grab what you want. The five senses help us to do that. Any opportunity that we have to move away from that is an excellent opportunity.

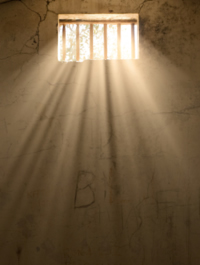

When we have those opportunities, and we search them out, you will find those opportunities everywhere, because there is no place where it’s impossible to practice the sacred. So that being the case, once you move into that posture of really practicing View and beginning to give rise to that recognition and beginning to see all extraordinary, compassionate, sacred objects as being something different — once you begin to see opportunities in every part of your life, you will begin as well to recognize Guru Rinpoche’s blessing. Once you recognize those opportunities and practice like that, Guru Rinpoche’s blessing will be everywhere.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo