The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Tools to Deepen in Your Practice”

When we are in love with our own minds—which is a lonely way to go, I have to tell you—when you are in love with your own mind, you can’t believe that you’re supposed to substitute anything for that stuff in your head, because it’s so phenomenal. It’s so impressive. It’s amazing what you can do with neuroses! I mean. . . Unbelievable! When you really believe in phenomena, like a child you can build it like blocks and do anything. But that accumulation of knowledge is practically worthless on the Vajrayana path when it comes to actual accomplishment. Sure you need to learn a lot in order to get to the point where you are practicing, and so we do have to accumulate some knowledge. But when you really want to accomplish, it’s wisdom that you must accomplish. And that wisdom is pure perception, the view—letting go of ego-clinging, opening up the grasping of the five senses, allowing oneself to view the emptiness of space.

What about the other leg or the other eye of Vajrayana which I said was compassion or method? When we practice early on in Buddhism, like when Lord Buddha taught, he taught that we should do no harm, that we should never harm any being. That was one primary level of vow taking that we should all take. Now, in Vajrayana, there is less emphasis on pure stark teachings like that, and more emphasis on something maybe a little bit more complicated. How can I put it?

It’s like this. In Theravada Buddhism, when you are accomplishing Dharma, what you are doing is purifying the mind and allowing the mind to relax. Ok. That’s a necessary step, a necessary stage. And part of that is to do no harm, to awaken to the realization that all sentient beings are equal in their nature and that they all strive to be happy, while not knowing how to be happy. For that reason, we should have compassion for them. We shouldn’t harm them because we know that each one has the Buddha seed.

In Vajrayana, that is already assumed. Everything in Vajrayana is built on the layers underneath it. Like Vajrayana is built on Mahayana, Mahayana is built on Theravada Buddhism. And they all become a little more fancy, explained, and mystical as they ascend.

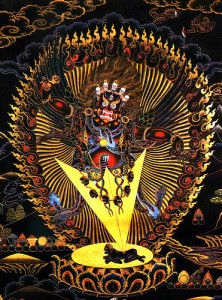

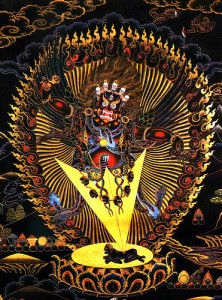

In Vajrayana Buddhism, for instance, we can expect that there will be practices in which there are wrathful deities. And we can expect in Vajrayana Buddhism, when you ask your teacher a question, you’ll get a frank answer. Now in Theravada Buddhism, there is not the same binding to the Guru. Your teacher is more like a companion on the path. A teaching monk, let’s say, can point and say, “This this,” “Accomplish this,” “Do that,” “Do that,” “Do that,”and guide you, and have encouraging words for you along the path. Whereas in Vajrayana, for the same reason that we accomplish wrathful practice, we sometimes have wrathful teachers. And we think to ourselves, “How can that be? I thought Buddhism was the peaceful religion? I thought you guys didn’t fight?” Well, we don’t. That’s not what is happening here.

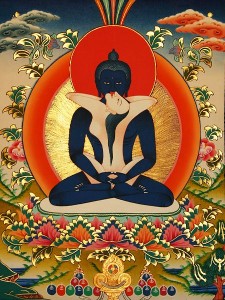

In Vajrayana Buddhism, the assumption is of the emptiness of all nature and the emptiness of dualistic existence. Therefore, I cannot find where I end and you begin. Who are you that you are different than I am? It’s not possible. Simply because of the clothing that you put on? The face you put on? Simply because of the ideas that you have about self-nature being inherently real? Should I accept that? No. And therefore, in Vajrayana, we have very active kinds of practices. We have Vajrakilaya, who’s like a pointy phurba on the bottom. You generate Vajrakilaya when you want to remove obstacles. And Vajrakilaya can look very fierce. In one visualization, in his two hands, he’s holding a phurba, a pointed knife, just like himself, and he’s rolling it around and he’s looking really wrathful. And he’s got all his wrathful clothes on. He’s got sometimes tiger skins and elephant skins and human skins and you think, “Whoa, what is that? I don’t know about this religion?” And that’s because originally, like in the early stages of Buddhism, in Theravada Buddhism, you want to relax the mind, purify the mind, do no harm and your accomplishment is more self-oriented.

Now in Mahayana and particularly in Vajrayana, we already assume that all phenomena is empty of self-nature. We already assume the truth of the unsurpassed primordial view. We already assume that all beings are essentially the same “taste” in their nature. We assume that. And yet, we cannot assume that there is no phenomenal reality because we seem to find ourselves in it. And you can’t go into a state of denial about it because we could prove you wrong. I could just stick a pin in your foot and boy, that’d show you. You’d get it real, real fast!

So we find ourselves here in Vajrayana. We are aware of this amazing reality that is the fundamental sphere of truth. At least somehow we are aware of it, somewhere, a little bit,ok, just a tiny bit, the sphere of truth. Yet at the same time, we find ourselves in phenomenal reality. We see the sufferings of the physical dimension, particularly the human dimension which are old age, sickness and death. We see all these things. And so while we understand on some level the emptiness of phenomenal nature, we have not yet accomplished enough to be able to hold the sphere of truth so smoothly that there are never obstacles. So in that case, we practice the wrathful deities. The wrathful deities are active in phenomena and yet we assume their nature to be the same as the Buddhas, the same as our Root Teacher; and eventually, let’s say if one were to accomplish Vajrakilaya as his or her root deity, eventually, we would understand our nature as Vajrakilaya.

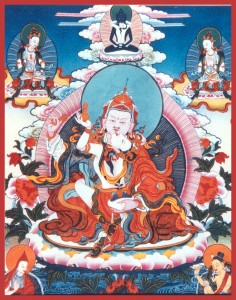

In fact, when we say that the Buddha is awakening, the Dharma is the method, enlightenment is the result, we can also say that the Dakinis are the activity of the Buddhas, and the Protectors and Wrathful Deities are the active expansion of the nature and of realization. We’re practicing all of these deities; and they’re all arising from emptiness and they all dissolve into emptiness. What we’re actually doing is engaging facets of our own nature.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved