An excerpt from a teaching called How Buddhists Think by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

People ask: “In your tradition, is Buddha like God?” No, Buddha is not like God. “Is Guru Rinpoche God?” No, Guru Rinpoche is not God. “Well, what do you call God in your tradition?” We don’t call anything God. There are gods, but they are not the goal. Westerners try to find a way around that, saying something like, “All right, then what is the goal?” I tell them, “Enlightenment.” They reply, “Okay, then Enlightenment is God.” No, it’s not. The goal is not anything as personalized and externalized as that. There is no “other.” The moment we are caught up in “self and other,” we have lost the essential Nature. We are fixated, stuck in duality.

This is about Awakening, which is the pacification of such fixation. You must understand the fundamental distinction between Buddhism and Western thinking––whether you are considering beginning the Path or are already a practioner. You must understand this difference, so that you will know what your true objects of refuge are.

The statement “I take refuge in the Buddha, I take refuge in the Dharma, and I take refuge in the Sangha” is an essential element throughout your practice of the Buddha’s teaching. What does this statement mean? It means you have looked at the faults of cyclic existence, and you have seen that it produces no real happiness. You have learned that the Buddha said there is a cessation of suffering, this cessation is Enlightenment, and it is also the cessation of desire. So you have decided to go for Enlightenment. That means you have to really understand the faults of cyclic existence––even if these ideas are difficult to swallow. It’s like taking a medicine that tastes bad until you get used to it. It is like that in the beginning.

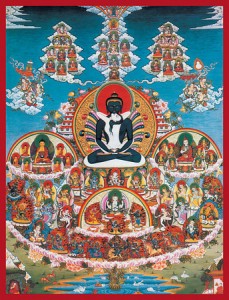

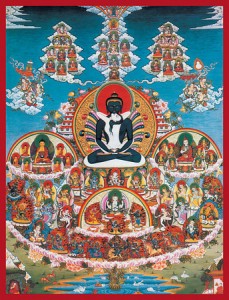

Having decided to take this medicine, you look at those who deliver it. We look to the Buddha, and this includes all those who have attained Buddhahood, not just the historical Shakyamuni Buddha. We look to the Dharma, which is the revelation or teaching brought forth from the mind of Enlightenment. And we look to the Sangha, the spiritual community to which we belong. It is the Sangha who are responsible for treasuring and propagating the teachings.

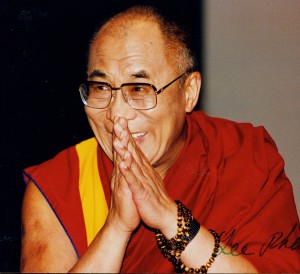

In the Vajrayana tradition, we also say, “I take refuge in the Lama,” who is considered representative of the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Without the Lamas, you would not hear the Buddha’s teachings. And without the Lamas, there would be no Sangha.

When you say you take refuge in all of these, what you are saying is: “I choose Enlightenment. I choose the cessation of suffering.” You move away from the faults of cyclic existence, and you remain focused on the ultimate goal.

In a deeper sense, however, you must understand that you are ultimately taking refuge in Enlightenment itself. You must understand it as both the Path and the intrinsic Nature. So you are taking refuge in the Nature of your own mind. If you understand this thoroughly, you can never be duped. But you do have to work very diligently and with discipline towards the goal.

The method is very technical, very involved. It isn’t easy because it must cut through aeons of compulsive absorption in self-nature. It must cut like a knife! It must be powerful––and it is powerful. You have to think of Dharma that way. The technology has to be strong––and real. You can’t just talk about it. There is work to be done!

Although it is strong, the technology is very flexible. You need not be afraid. You will not be forced to go any deeper than you want to go. You have the right to practice gently. You will still be accumulating causes for a future incarnation as a human with these auspicious conditions, and then you will be able to practice well and dilligently.

There are people who only do very small, very gentle practice. And that’s fine. There is a large tradition of that in the Buddha Dharma. There are also people who are more deeply involved, though in a mediocre way. They practice an hour or so a day. They do a good job, and they’re faithful, and that’s it. Then there are people who practice many hours each day. They continually try to propagate the Teaching, and they work very hard. So you have a choice. You can determine the level of your involvement.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

To download the complete teaching, click here and scroll down to How Buddhists Think