The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Tools to Deepen Your Practice”

In order to practice Vajrayana, for instance, there has to be some certain capacity that the student has, or some previous karma that now comes forward and comes to bear, or Vajrayana simply would not work. Indeed, for certain kinds of students because they practice very superficially, Vajrayana , would be like just reading Sutra—just reading it, reading it, reading it, reading it. You may glean some information, but you will never accomplish any wisdom that way.

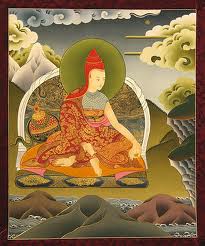

So when we first come to Vajrayana, we are expected not only to read, to learn how to pronounce, to accomplish the tune; but we also have to learn how to visualize. We also have to learn how to allow the five senses to dissolve into the sphere of truth, which is emptiness, and that means letting go of perception. And that’s the first step towards meditating on emptiness, or rather as we do in Vajrayana, dissolving or realizing the essence of all nature to be empty and then arising from that empty nature as the deity or as a wisdom being. This is basically the meat and bones of Vajrayana, that generation of the wisdom being by first dissolving into emptiness.

If a person who is studying Theravada Buddhism (that’s the early stages of Buddhism that Lord Buddha taught when he was actually physically alive), practices like that, they are letting the mind relax. They are using some kind of method like allowing the mind to rest on the breath, to simply breathe, to simply be like that. But ideally, when a Vajrayana practitioner prepares to really generate the deity and they’ve done their taking refuge and all the steps that precede:the promising, the Bodhisattva promise and all the prayers:and they actually get to the part where there is the dissolution or the original view of emptiness, they are not, at that point, relaxing the mind. Because if we’re simply relaxing the mind at that point, we are technically practicing Theravada Buddhism. It’s a little different.

It’s ok to start that way, but again, we’re talking about going more deeply into our practice. So when a Tantric practitioner meditates on emptiness in order to pave the way for the rrising of the deity, what you really do at that time is to open up the senses in the sense that the senses are grasping things. They see “this” or “this”. I hear “that”. I smell “something”. So the senses are grasping things. The senses are actually the children of the original conscious assumption of nature being essentially real, or of phenomena being essentially real. And so the senses arise from that assumption. It’s a chicken or egg thing. It’s opposite what you would think. The senses arise from the assumption of consciousness as being inherently real. And so the senses’ job is to grasp!

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved