The following is a video teaching recorded live at Kunzang Palyul Choling:

Teachers

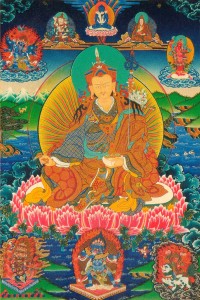

The Great Mother

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Dakini Workshop

According to the Buddha’s teachings the great expanse of unborn voidness is the great mother, or the spirit of truth. All potential and all potency, all movement and all display arise from the unborn sphere of truth. According to the Buddha’s teachings, all display, all movement, all potency and all emanation, and in fact, all phenomena of any kind not only arise from the unborn sphere of truth but are inseparable from emptiness, are the same taste as emptiness and therefore are the same nature as emptiness. We should meditate in that way.

The great foundation, the ground, the great basis is the unborn and yet spontaneously complete sphere of truth. Everything that can be seen, touched, felt, tasted, smelled, rises from the sphere of truth. Therefore all conclusions drawn from any such observance also arise from the sphere of truth. The basis of every thought, of every feeling, of every sensation is the same essence as the unborn sphere of truth – inseparable, indistinguishable. Therefore it is undeniable that all phenomena are empty of self-nature. We should meditate like that.

Therefore, when we take refuge, we take refuge in the great mother. For those of us that practice the path, in order to achieve supreme realization, practice to achieve that view. When we take refuge, we take refuge in the understanding that the basis of that refuge is the seed nature, the Buddha nature, which is inseparable from and arises indistinguishable from the unborn sphere of truth. We should meditate like that.

We take refuge on the basis that the ground nature is the Buddha nature. We take refuge as well in the path, which is the display of that foundational nature and we take refuge as well in the outcome, or the fruition, which is enlightenment itself. Although we hold these concepts in our mind as distinguishable concepts they are in fact indistinguishable and inseparable from, and the same as, the foundational nature.

Knowing these things to be true, we can try to understand the many ways in which our practice occurs. Our practice occurs through a certain systematic representation of enlightened images. Most of you recognize this systematic representation as being primarily the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha and then, in a more inward way, the Lama, the Yidam (meditational deity), the Khandro and the Dharmapalas. And of course, in the most secret way, we understand the ultimate objects to be the channels, winds and fluids that are the displays of our own enlightened nature.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved

The Suffering of Cyclic Existence

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “The Faults of Cyclic Existence”

So this is not particularly a pleasant subject. Every part of you will resist talking about it; every part of you will resist internalizing it. But at this point you have to exert a little discipline. You have to begin to use discipline by examining, really, whether or not the things that you have done to attain happiness have ever really lasted. You should examine whether positive thinking or any of the things that you have done, or falling in love, the things that have made us happy, whether the happiness has carried through into the rest of our lives, and whether it has lasted for our whole lives so far. You can really look at it that way. And then maybe from that point of view, you may be able to gradually introduce yourself or discipline yourself into thinking about the faults of cyclic existence.

The faults of cyclic existence are obvious in some ways. According to the Buddha’s teaching everything in cyclic existence, every experience—life, death, joy, pain, happiness, unhappiness, poverty and wealth, having and not having, all the different experiences that we experience—all of them are impermanent no matter what the particular experience that you have is. Whether it is blissful and wonderful; whether, as in the Breck commercial, you are experiencing one of those love affairs where you bound across the field at each other every day, and it is always sunny and flowers in the field; and you catch each other rapturously in each other’s arms and smouchy, smouchy and all that kind of stuff. Even that is impermanent. Especially that is impermanent. That is most certainly impermanent, even if you are extremely beautiful, so beautiful that you could remain happy if you just got up and looked at yourself in the mirror because you are so beautiful. There are some people who are that beautiful. I haven’t met too many and I am not saying whether anybody here is that beautiful. But anyway there are people who are that beautiful, that all you have to do is look at yourself and you just go ahhhh! Even that is impermanent. Especially that is impermanent. And defying the law of Estee Lauder, eventually it will go away.

The joy of having children: It is such an incredibly joyful experience to know that you can have a child, and to have a child sleeping peacefully in your arms and looking up at you with those beautiful little eyes, and tiny little rosebud mouths with a little trickle of milk coming down the side. So blissful. And then they become teenagers. That is impermanent. All of the things that you can experience… There is my teenage son over there. I am saying this for his sake. All of these things are very blissful and very wonderful, but extremely impermanent. Also suffering is extremely impermanent. ‘This too shall pass’ philosophy works. It works because everything is impermanent. It also works for happiness. That is the problem. Both the happiness and the suffering are impermanent.

Any pain that you feel, any suffering that you feel, any longing that you feel, even lifelong poverty is impermanent, because at the end of that life of poverty one will die. And after dying maybe you will be reborn rich. Who knows? But your particular circumstance, whatever it is, is always impermanent. That is the only thing that is consistent about cyclic existence, impermanence. According to the Buddha’s teaching.

Each of the six realms of cyclic existence… (If you are interested in hearing what those realms are you can purchase tapes that we recorded here. There was a workshop recently given in which I described the six realms of cyclic existence according to the Buddha’s teachings.) Anyway, in each of the six realms, there is a particular kind of suffering that is associated with that realm; and it has to do with the particular karma that it takes to be reborn in that realm. Each of these realms is different and unique, and they all have impermanence in common. They all have their cyclic nature in common. They arise from cause and effect and the cause and effect is continual and begets the next cause and effect. One begets the other. It is a constant begetting of more and more cause and effect. So they have that in common. But each particular realm has its own form of discomfort and suffering.

According to the Buddha’s teaching, you experience rebirth because of desire. Because of desire you are born into one of the six realms. Rebirth is experienced because of desire due to the belief in self-nature being inherently real. Now that is Buddhist lingo for ego. Actually due to the grasping of ego as being inherently solid, due to that grasping and perceiving phenomena as being external because of that grasping to ego as being inherently real, due to the belief in the division or distinction between self and other because of the belief in ego as being inherently real, due to that kind of faulty perception, one revolves in an illusory state, a state that seems to us very, very real. And that illusory state is cyclic existence.

Due to the desire that is associated with the belief in self-nature as being inherently real, we continually achieve or experience rebirth. According to the Buddha’s teaching, it is not necessarily a linear experience. We comfort ourselves with a very current idea that one progresses in a linear way. You should understand that this is a very new philosophy. This is not what the older religions, the ones that are more established, the ones that actually give the accomplishment of enlightenment, necessarily teach. Any form of Buddhism that has appeared in the world has taught that one experiences rebirth because of the karma of the mind and not necessarily in a linear progression. The idea of linear progression is new. If you think that is the only way in which birth is achieved, you should at least give yourself the opportunity of examining some alternative philosophies. The new idea associated with linear progression seems to be: Now that I am a human being, I will always be a human being or better; that I have come to this point and this is the level that I am at and I will always be at that point or better. So I am doing good. I am okay.

This is faulty reasoning. You are not taking into account that you have lived countless lifetimes. Countless lifetimes. You can’t name the time when it started. We are talking about aeons and aeons of cyclic existence. Such a long time that you have experienced rebirth that you have had many, many different lifetimes in many, many different forms. It is impossible to experience the ripening of all of your karmic causes, of all of the karma that you have accumulated over a period of time. It is impossible to experience all of those ripenings in one lifetime. Impossible. It is simply not dense enough. It is not possible. It would be like trying to put an ocean full of cause and effect relationships into a cup. It is simply not possible. So that being the case, you have lots and lots of latent karmic causes that have not ripened and cannot ripen, will not ripen, in this lifetime. So according to that thinking, all of us actually have the karma for being reborn in the lowest, hellish realm. And we also, all of us, have the karma for being reborn in the highest god realms.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

The Power of Intention

[Adapted from an oral commentary given by His Holiness Penor Rinpoche in conjunction with a ceremony wherein he bestowed the bodhisattva vow upon a gathering of disciples at Namdroling in Bozeman, Montana, November 1999. —Ed.]

Sometimes, although you are maintaining the bodhisattva vow internally and your intention is purely to benefit others, externally it may appear through [your] conduct or speech that you are breaking the vow. Although it may seem that a failure is occurring, if your actions and speech are motivated by bodhicitta, then no failure is occurring. That is referred to as a “reflection of failure.” For example, if it is necessary to commit a nonvirtue of the body or speech for the sake of benefiting others, that is permissible. In fact, not to do so could constitute a breakage of the bodhisattva vow. The motivation must be very clear. Whether your actions constitute a failure or not is determined by your own mind’s motivation. Here it is crucial to be careful, since losing the vow means taking lower rebirth.

From “THE PATH of the Bodhisattva: A Collection of the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva and Related Prayers” with a commentary by Kyabje Pema Norbu Rinpoche on the Prayer for Excellent Conduct

Compiled under the direction of Venerable Gyatrul Rinpoche Vimala Publishing 2008

Addicted to Happiness

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Faults of Cyclic Existence”

I would like to take a moment to look at that. You should understand your own psychology enough to really look at yourself and see that mostly everything that you do is an attempt to be happy. If you look at the way we dress, the way we eat, the way we play, the way we work, all of these are meant to fulfill in some way the need to experience happiness and stability. All sentient beings have as their primary, motivating focus the urge to be happy. That is common in all of us. That is part of our basic psychology. You are not bad if you are trying to be happy. This is normal. No one is bad if they are trying to be happy. Every form of life, every bit of cyclic existence experiences that urge to be happy. In fact that can be seen as a brotherhood among us. It can be seen as a way to understand that we are absolutely kin, even in terms of understanding one another’s behavior.

You may not understand the behavior of someone who is very rough and gruff and insensitive. You may not understand the behavior of someone who is a thief. You may not understand the behavior of someone who is very needy and whiny. You may not understand the behavior of someone who is very boasting and gregarious. Whatever your particular personality is like, you won’t understand the other one. Trust me. Whatever yours is like, the other one is not very easily understood. But you can come to understand anyone if you come to understand that each of us, in our own weird way, is trying to be happy. Even the thief is trying to be happy. He thinks that is how he is going to be happy. The misunderstanding is that he thinks that is how he is going to be happy. The whiny kind of needy person is trying to be happy. They think they will get what they need if they continue that behavior. The boastful and gregarious person is trying to be happy. They think that they will be approved of or they will get what they need if they continue in that way.

All of us, equally, are trying to be happy. That is what makes us brother and sisters, if nothing else, because that is our psychology. And because we do not want to be unhappy. we wish to be happy, we resist examining the faults of cyclic existence. It is a downer. There is no getting around it. It is not what you want to think about because if you think about that you kind of get the icky-stickys. It’s just not what you want to think about. It’s just not so pleasant. However, if you think about love, or if you think about beauty, or if you think about positive thoughts, or if you just examine rainbows or do all these wonderful things that you have found make you happy, you think that is the answer. That is what I want to do. It will make me happy for a little while. And we are happiness addicts; we are stimulation addicts; we are instant gratification addicts. We want to have that little hit of happiness; and we don’t really care who we have to steal it from, much like a thief.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Motivated by Kindness

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Faults of Cyclic Existence”

We have been brought up to understand that we are the most powerful country in the world. And we are, of course, the most enlightened people in the world; and we are, of course, the most advanced people in the world; and we are, of course, because we have Estee Lauder, the most beautiful people in the world. We are brought up with all these different beliefs. And whether we swallow them consciously or not, subconsciously they are in there somewhere rattling around, and we have this faith in our way of life. One thing that we can do is to think of ourselves as able to help others. One thing that is very popular in our society is the idea that it is a beneficial thing and a good thing and a virtuous thing and a fulfilling thing to help others. We are always looking for fulfillment. So the idea of compassion is a way to move ourselves into a foundation for meditation and practice. In my own experience (and I don’t claim to be such an experienced teacher), but in my own experience I have found that if I go to a new place that has never heard about the Buddha’s teaching, or if I go to a place that has heard a little bit and wants to hear more, or even if I have gone to students that have studied Buddhism for some time, if I want to touch them or refresh them so that they can continue in a determined way in their practice, or have them open up to the potential of practice and be stabilized to the extent that they can begin to practice earnestly, I can always rely on the idea of compassion to do that.

Westerners are excited by the idea that they might be able to benefit others. They are aware to some extent that the rest of the world is suffering. We don’t like to think about it, but to some extent we are aware that poverty exists, and hunger and sickness. I have found that Westerners are kind people. We are kind people. We want very much to end suffering; we very much want to help others. And there are many people who will practice if they really understand that this meditation will help them bring about the end of suffering for other people, will help them be a helper to others. They will practice for that reason. But strangely they will not practice to end their own suffering. They will continue to try to manipulate the circumstances in their life, or change things around, or try this or try that; but they will not really develop a firm foundation of practice because they themselves are suffering. They are not sufficiently motivated by their own suffering. It is a strangeness in our culture. It is not found in other cultures. But we will practice to benefit others.

This group, the core group of people who have been practicing in this temple for some time, came together because the people of earth were suffering, and the group wished to maintain a 24-hour a day prayer vigil. That is a dynamic of this organization. It came about so quickly and in such a stable way because the people here were greatly moved by the suffering of sentient beings. They knew that this kind of practice—the practice that brings about the end of desire and brings about supreme enlightenment—is ultimately the way to bring about the end of all suffering. For this reason, this family, or group of people, actually came together to practice.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Sustainable Foundation

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Faults of Cyclic Existence”

I have found that after a certain point, if compassion is the main motivation to practice, it will sustain you; but it constantly requires inspirationbecause we sort of become drawn back into ourselves. You know how you do that. You sort of wake up in the morning and think, ‘Today I am going to live a spiritual life, and I am going to help everyone, and I am going to be nice. I am going to be good and that is it. That is the kind of day I am going to have.’ And somewhere around 4:00 (or at least it is 4:00 for me), you need a little inspiration. Well, we are like that with our lives. We have moments of touching, moments of experience of spiritual point of view. We have precious moments; and in those moments we think, ‘This life is only important if I accomplish meditation or if I accomplish enlightenment. This is very important. This is really the meaning of life; and I have a sense of the meaning of life; and I have a sense that kindness and love are the core elements in life; and that is what it is really all about. And I am changing my life starting now.’

Two weeks after that point, maybe three days, we start to wear down a little bit. I have found that in practicing the Buddhadharma, even if in the beginning we are on fire—your heart is just on fire with compassion, and you feel so strongly the sense to benefit all sentient beings—unless inspiration is constantly experienced or given, or had in some way, that that will wear thin. At that point, even Westerners must begin to understand the foundational concepts associated with the Buddhist thinking. That foundational concept I will entitle “The Faults of Cyclic Existence.” If a real competency in understanding the faults of cyclic existence is not adapted at this time, the foundation is incomplete. Because it is not sufficient only to practice in order to benefit beings and for compassion if one does not really understand the faults of cyclic existence. So I would like to go into that.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Covering the Bases

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Faults of Cyclic Existence”

I just wanted to take a moment to thank you and give some little cookie as to what the prayers are all about and as to why we use them as we do. I think that if you are not used to pronouncing Tibetan you must have something of the same experience that I had when I first began to learn these prayers and began to pronounce them. I remember being a little Jewish and a little Italian, I rolled up my eyes and did like this and went, oy! It seemed to me so cumbersome. It seemed to me intensely uncomfortable; and I just could not believe that I was investing myself in doing this. But eventually over a period of time and patience, which is not something I have a lot of, I did manage to listen to these prayers in such a way that they became meaningful to me. And now that I have come to understand something of the meaning of them, I really take a great deal of joy in reciting them. I feel a tremendous amount of joy and regard for taking the time to recite these prayers on a regular basis and in a heartfelt way. They are truly wonderful and a great blessing.

For those of you who come every week, or come fairly regularly, you will find that there are many times that I will repeat things that I have already taught. There is a reason for this; there is a method to my madness. First of all, I have found that almost never do people internalize philosophical concepts the first time they hear them. Almost always is it necessary to hear them again and again and again. Actually it is better to hear them in different ways, and then they begin to become a part of us. It is almost like climbing a mountain from several different directions in order to understand the shape of the mountain. If you can’t look at the mountain as the Buddha might look at it, from kind of a bird’s eye view, or an elevated posture, you have to rely on climbing the mountain in order to understand its topography, in order to understand its shape and its form and its dimension, and how big it is, and to really internalize what the mountain is all about, to see all its different faces. One climb won’t do it and climbing the same way all the time won’t do it. It seems as though we have to climb from all the different beginning places, from all the different sides of the mountain, in order to really accomplish understanding what that mountain is.

I feel that philosophy and religion are something like that. In order to really understand them and internalize them, they must be approached again and again and again; and they must be approached at different times and from different angles. For one thing, you are constantly changing. There is nothing about you that is permanent. You are constantly growing and changing; and even from day to day, your particular mood, your particular depth, your particular understanding is very flexible. It is constantly changing. What you understand one day, you might not understand the next day. And I am sure that you have had experiences like that where you have read a religious thought or a spiritual thought or had an experience in your meditation that one day seemed unbelievably deep, seemed to you to really click, seemed to really mean something to you. And then the next day, you might read it and you might as well be reading a bubble gum wrapper. It is just about that meaningful to you. So we change constantly. There is nothing about us that is permanent, plus the fact that our karma is constantly changing. Of course, that is what makes us change. Different catalysts cause the ripening of different karmic structures, different karmic events. We are constantly effected by these ripenings. From time to time, obstacles arise that effect our minds and our perception. And also we have a characteristic way of understanding. There is a characteristic karma that is our karma. Each one of us has our own particular mode of understanding.

I was listening to the radio yesterday for a little while and there was an interesting example of that. A man who was a linguist would go to different movie stars and different movie sets and he would teach people how to speak in a different dialect or with a different accent. He was so proficient; he was just amazing. He could speak three different dialects of… How can I explain this? He could speak English with an Irish accent, but he could sound as though he had come from three different regions in Ireland. He could sound like any different state in the union. Each state has a characteristic way of speaking. Not all Southern states sound the same, not even all Appalachia sounds the same. Anyway he was so good at that that he could make a difference between the Bronx and Brooklyn; he could make a difference between India. He could act as though he were speaking from a specific region from any country in the world, and he could teach anyone to accomplish that.

His observation, and the reason why I am bringing this up, is that people learn differently and you have to be skilled in many different ways in order to teach people. He was describing Jane Fonda and he was saying that she has an incredible ear. Only three two-hour sessions, I think he said, and she could mimic a certain regional Appalachia dialect that was very difficult to accomplish and very specific; and she had an ear that was like a tape recorder. That was the way that she learned. A lot of what she learned she had to learn from ear. She couldn’t really learn it by reading it as she could by hearing it. And then he described Charlton Heston. He is not able to learn by ear at all. He has to learn it by phonetically spelling out the accent. Then he can read it from cards, and he can do it perfectly that way.

So each of us has a characteristic way in which we learn. It is not as simplistic as that. It is not that some of us hear better than read or read better than hear. There is that, but there is a characteristic karma or an outlay or a fabric that our minds seem to have and the way in which we learn. It may be that you may hear an entire philosophy laid out in a very explicit way. It may be just perfect. It may have everything in it, and it may not make any sense to you. It may be like Jane Fonda trying to read a card or Charlton Heston trying to mimic a voice. It may not do anything for you. And yet something may be laid out in a different way and it may be fairly sketchy; and from that you may have an understanding that is deeper than the one that you could have gotten from a very specific teaching.

So we try to cover all of our bases here and make sure you hear this teaching in as many different ways as possible. And for those of you who are here for the first time or come only once in a great while, I try to not build the classes one on top of the other too much so that when you come here, even if you only come occasionally, you can come away with a whole cameo piece, or a whole thought or a whole teaching that you can use for your own benefit and also eventually to benefit all sentient beings.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

Preliminary Practice

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Faults of Cyclic Existence”

I am grateful to those who go through the Sunday prayers without having the foggiest idea what they mean. I commend you completely with all my heart and soul, if I had one. (That is a joke. You see according to the Buddhist philosophy there is no such thing as a soul.) It is considered that there are three objects of refuge: the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. The Buddha, of course, is the enlightened mind. The Dharma is the speech or teaching of the Buddha, the path of the Buddha; and the Sangha is considered to be the religious or spiritual community that propagates the Dharma, that brings about a way for us to practice. And these being our objects of refuge, we consider that all of the teaching and all of the opportunity that we have to practice actually comes from the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. So we feel that before beginning any practice it is good to make offerings. And when reciting these prayers, once you understand what the prayers are about, you can visualize certain offerings.

It is considered that it is good to request the Buddha to turn the wheel of the Dharma, or to continue to offer the path of the Dharma. It is a combination of offering and request, honoring and praising. It is our custom to do these things before we actually begin to accomplish a practice or hear a teaching. Some of the meanings of the prayers are pretty evident when you read them. Yet, you must understand that almost everything that exists on the Vajrayana path seems to exist on three levels of meaning. I am not sure why it happened that way. I think that it is just a propensity for secrecy, or drama, or something wonderful like that. It appeals to me very much.

At any rate, I think that what is addressed here are different levels of understanding. There is a preliminary level of understanding in which one first approaches the path and, almost like walking into a room, you need to figure out where the door is, how to turn the handle. We have to turn on the light; we have to figure out where the table is so that we don’t bump into it. It’s that kind of thing. We have to look at the bones of it, or the structure of it, and the inner and secret levels of meaning. One actually develops a capability for understanding as practice begins. Almost never, at least traditionally, are deeper, very mystical teachings given right at the onset of engaging in Dharma practice because it is considered that the mind needs to be deepened and gentled. At the point when that process begins through the use of preliminary practice, then additional teachings, intermediate teachings, and then ultimately the deepest teachings are givenThere are some lamas that deviate from that for their own reasons. But it is considered, from the traditional point of view, that you can give the deepest teachings to someone, but if their minds are not prepared for it they will not really accomplish the deepest teachings until they go through a period of preliminary practice and preparation. And I, for one, feel very strongly that that is the case.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved

The Path to Ultimate Happiness: Advice from His Holiness Penor Rinpoche

The following is an excerpt from advice offered by His Holiness Penor Rinpoche during the New York Retreat in 2005:

Now we have this Precious Human Birth it is very important that we do something about it. Whatever kind of aspiration or attainment that we may achieve in this life, the only thing that really counts is what we do in this present time. At the end when we die, we can take nothing with us. Even though a person may have wealth comparable to that of the USA, he is unable to take even a small needle with him when he dies. When our time comes, we have to leave our spent body behind. If you have been practicing Dharma, then Dharma is the only thing you can take with you. But if you have committed non-virtue then the karma you generated through that will be the only thing you can take with you. Whether this is true or not, all you have to do is to reflect upon it thoroughly, then you will know for certain how true it is.

For this reason, it is very important to have faith in Dharma and practice accordingly. If you have doubts about the practice, then you can gain nothing from it. If you practice Dharma without doubt and with wisdom, then only positive results will ripen up for you. Buddhist Dharma has many special qualities; in particular, the practices in which you have just joined this year are part of the practice of Dzogpa Chenpo, which belong to the most supreme, most precious part of Dharma practice.

It is very difficult to practice Dharma due to the karmic and emotional defilements which keep us attached to the mundane worldly kind of existence, it is as if you have to climb a mountain with a burden of heavy baggage on your back. You have to undertake a very long and arduous journey in your Dharma practice, but it is very easy for you to lose your footing and fall down on the way. Furthermore your fall back down again will be very swift, much swifter and further than for those who do not carry much of this kind of baggage. When you climb up a steep mountain, it is very difficult and very tiring, similarly the practice of Dharma is also challenging. To reach the ultimate happiness you have to maintain Dharma practice diligently. When you practice Dharma, you have to abandon any doubts and practice it with a single-pointed mind. There is no need to have doubt concerning Dharma because, since time without beginning, an ocean of practitioners has already attained enlightenment through this kind of practice.

These people also had the strong wish to attain happiness and they put all of their efforts into the practice. You only have to listen to what they have achieved, to realise the vast number of realised masters who have already succeeded in their endeavour to achieve lasting happiness and realisation. For you, it is impossible to actually check the nature of the qualities of Dharma, to judge whether they may be good or bad. If you possessed qualities higher than those of Guru Padmasambhava or Lord Buddha, then you might have a more objective view of the qualities of Dharma. At the moment it is impossible for you to have such an objective perspective, for it is no different from a blind person who says he wants to visually check his own body – how is it possible? Instead of having doubt in Dharma, it is better to have faith and trust and to practice as much as you can.