By Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo

An excerpt from a teaching called “How Buddhists Think”

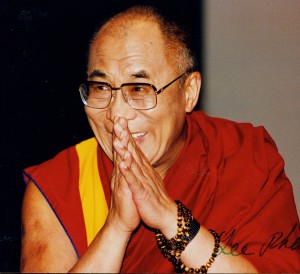

Some years ago, His Holiness the Dalai Lama took part in an interfaith discussion at a cathedral in Washington, D.C. The Episcopalian ministers and Catholic priests repeatedly stressed the sameness at the core of all religions. His Holiness stood up and said that in some respects we are all the same: we all wish for peace on Earth, we wish for the benefit of beings, we wish for the end of suffering, we wish to attain a level of consciousness in which we are unified with our optimum goal, whatever that might be. “But,” he said, “between your religion and my religion there are fundamental differences. And that has to be okay. There has to be unity in diversity.”

Although I would certainly never speak for the Dalai Lama, I assume that the “fundamental differences” to which he referred have to do with Buddhism’s lack of an external God. This is generally not understood by Westerners. The Buddha’s teachings do not advocate the attainment of oneness with a God, with anything external. Instead, the Buddha teaches the essential sameness of all phenomena, pointing out that in the beginning there was no distinction. The Buddha tells us that such a distinction exists only in our mind, which is fixated on self-nature as being inherently real.

In truth, our Nature is all-pervasive. There is no separation. There is no distinction. When Realization is achieved, it is a non-specific awareness, a luminosity, an innate wakefulness. The process of fixation, of contrivance and distinction, is pacified. That is not the same as attaining oneness with anything external. The Buddha leads us to pacify the delusion that causes fixation on duality.

There is no optimum state one has to create, no supreme being towards whom to move. For a Buddhist, the goal is awakening. It is an awakening to the Nature that cannot be nearer, or stronger, or better than it is now. It can never be tainted, pushed away, destroyed. It remains stable and unchanging. It is simply “Suchness.”

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved

![bodhisattvas[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/bodhisattvas1.jpg)