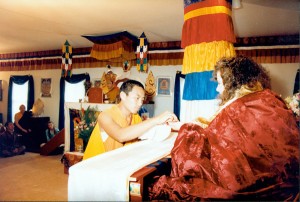

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

On the first day, it is Vairochana Buddha that will appear. He either manifests in the form of a Buddha, according to our beliefs, should we have the capacity to recognize, or he will manifest in the form of dazzling blue lights and geometric shapes. These dazzling blue lights are just that—they are dazzling. They are unlike anything we have ever seen on the physical level. They will knock you for a loop. Literally knock you for a loop. It will be unlike anything you have ever seen. The ultimate light show, friends. And it will be different than you have ever seen it. So one needs to practice in order to be able to recognize the nature that is Vairochana Buddha.

At the same time that this almost violent, dazzling, ultra-dazzling blue light will appear, another softer white light will appear. The softer and white light will be more welcoming, but this softer white light corresponds to the world of the gods. Do not follow. Go to that light which is dazzling, perhaps more unfamiliar, perhaps more frightening. Call out to the Buddha. Try not to take the easiest way out, but ask yourself, require yourself to recognize the Buddha. If the person seeing this has no idea of what is happening, the sheer brightness of the light of the Buddha is somehow terrifying. If they haven’t practiced, you see, they are unused to it, so it is terrifying; and one will be more inclined to follow the light of the worlds of the gods, as it is soft and pleasing. So beware of that.

Here are the two correct attitudes, according to this lama, that are very helpful to adopt in order to face the situation. The first one consists of becoming conscious that the blinding blue light manifests the presence of Vairochana Buddha. So we pray every day from now until the time of our death, and especially around the time of our death, that he will dispel the suffering and phenomena of the bardo. And particularly when we see him, when we see this very bright blue light or when we recognize that the Buddha is present, we pray to him and ask him to dispel the delusion and make the way clear for us. The second method requires more profound knowledge than the first one. The first one, you only have to have heard; literally, you now have enough to do that. You have heard, and through the force of your caring about this hearing and wanting to internalize it, it is that force that will make you remember that you have heard that Vairochana will appear at this time. Now you know that. You are expecting to be in the bardo; you are expecting to see light that you are uncomfortable with. You are expecting to see things you do not recognize or feel familiar with, and you will know not to be afraid. That’s the first way, you see.

The second way requires more knowledge than the first way, and it involves recognizing that the light which appears that is Vairochana has no external existence separate from oneself. That it is the manifestation of one of the five Buddhas present within our own mind. And he says here that, “Their manifested aspects are externally expressed, but in truth their light has no intrinsic external existence.” This blue is actually the luminosity of our own minds; yet we cannot recognize it because we have not become familiar with our own minds. And so the second method, in order to get through this particular aspect of the bardo, is to recognize that this has no inherent existence outside of ourselves. That this is, in fact, a display of our own inherent Buddha nature, and in that way, to become familiar with it and non-dual. Remaining fully aware that the light and the mind are one will free us from the suffering of the bardo. On the other hand, if we are enticed by the white light of the god realm, we will be seduced to be reborn as a long life god—the god that lives a long time and smells good and looks good, feels good, but then eventually, pffft., A bad end to that vacation. So we do not wish to be reborn in the god realm. Do not go for instant gratification in this case. Trust me on this one.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved