An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo from the Vow of Love series

If you’ve never practiced the Buddhadharma before, or if you’re interested in practicing, or if you have practiced some general meditation and you feel it’s time to move on to a path that is more stable or well known, then you’re in a perfect place for this teaching. You can start practicing one of the most important teachings of the Buddha right now. You can begin to cultivate the mind of compassion. How might you do this? First of all, you might look around and examine physical existence.

In America, we hide our suffering. We have very little knowledge of real suffering, and I think that’s one reason why it’s very difficult for Westerners to practice a pure and disciplined path. We think we understand suffering because we have experienced loneliness, or because when we were kids we had the measles, or because we have gone through marriages and divorces. Or maybe we’ve seen some sickness or poverty. For these reasons, we think we understand suffering, and we do to some extent. These are valid sufferings.

But there’s a funny thing about our culture that we must understand. We are actually hidden from the sufferings of our culture. When people are deformed, handicapped, mentally or terminally ill, they are taken away from the mainstream of society and they are hidden. Or if we are considered unpresentable to most people, we have plastic surgery or we have some kind of therapy that makes us like everyone else. In fact, if we examine the healing process in American medicine, part of that process is to become like other people. We are made to look like other people.

In other countries around the world suffering is more evident, for many different reasons: those countries may not be as technologically advanced as our country, or their culture may be an older society in which suffering has become more the norm and it is not such a shock to see it. Or perhaps poverty is a factor.

I will describe how I felt when I first went to India. I couldn’t bear it. I don’t claim to be so compassionate; I too have to cultivate the idea of compassion every day. But I remember seeing people walking the streets with arms and legs missing, eaten up by leprosy. I saw mothers and fathers maim their children, not because they hated them or because they were cruel to them, but because that would give them a deformity they could use for begging. That would be the only way they could ensure their survival. There was no other way for them to get food. What do we do for our children? We might send ours to school. In the streets of India, they have to prepare them in a different way.

Suffering is a part of the fabric of the society in India, and it’s very evident. I remember walking down the street in Delhi. There was a young boy who must have been twelve; it was hard to tell, he was so small. He was lying on a rag, a tattered blanket, and he was dying. He was so thin that he looked like the pictures of starvation we see from Ethiopia. He was beyond thin. His bones were sticking out, his belly swollen, his tongue hanging out. And next to him were a few coins and a candy bar. Someone had thrown them down for him.

We don’t see that in our culture. We don’t understand it. We think that the things we’ve gone through – the divorces, not being able to pay the light bill, the heartbreak of psoriasis, the things we consider so awesome – are the real sufferings of the world. But they are not all the world has to endure.

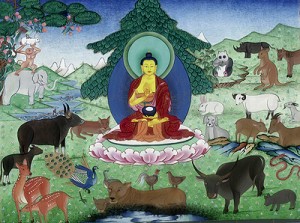

Look at the animal realm. We know what our animals are like. They get fed everyday and they have it pretty good. But not all animals are like them. If we go to different countries, we see beasts of burden that are treated in horrible ways. We see animals that are denied their natural environment.

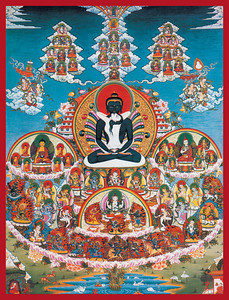

Humans and animals are only two life forms. According to the Buddha’s teachings, there are many different life forms, many of which are non-physical. How we appear, how we manifest, what form we take has to do with the qualities of our mind. If we are filled with hate, we are reborn in a hell realm. Why is that so hard to understand? When you are filled with hate now, even as a human being, aren’t you in your own private hell? Have you ever gone through a period where you were so filled with anger that everything you saw became ugly and you managed to distort it somehow? Each of us has lived in a private hell. Why is it so hard to believe that we are capable of living in or creating a situation like that? If your mind is capable of having a nightmare, then rebirth in a hell realm is a possibility.

Have you ever been needy? Have you ever gone through a period in your life when you needed approval, or love, or some kind of nourishment so badly, that you were in a state of despair? When people did reach out to you, they couldn’t get through? Each of us, for at least one moment in our lives, has experienced this. Why then is it so hard to understand that these kinds of existences really do exist?

Having understood that this is logical, having examined your own mind truthfully – and truthfully is the key – and found the residue of these experiences in your mind, you can allow yourself to go more deeply into the recognition that the Buddha was right. There is suffering in cyclic existence.

We have to think also of our own suffering. We must think that even if we have a TV, a car, a house, and all of the things that we are taught to desire, there will be a point at which we cannot take them with us. There will be a point at which they will do us no good. That point, of course, is death. All of the efforts that we’ve gone through to get those things will have been wasted.

Long-time Dharma practitioners may think, “I really wish she’d get on with it. I know this.” I have to tell you, if you really knew the truth of suffering, there would not be one moment that you did not practice with the utmost compassion. There would not be one moment when you thought only of yourself and your needs, and of the temporary gratifications you think you must have. Yet you still have many of those moments.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

![gold_road[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/gold_road1-170x300.jpg)

![broken-chain-small[1]](https://www.tibetanbuddhistaltar.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/broken-chain-small1-300x207.jpg)