The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Marrying Spiritual Life with Western Culture”

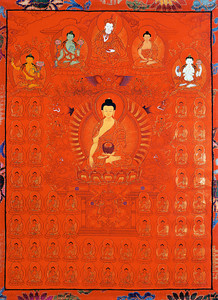

It’s interesting to realize that when we come to the temple, we’re already interested in Dharma. Why are we interested in Dharma? There are lots of different reasons. We like the look of it: It’s interesting and exotic. The statues are really cool. The colors are nice. We have a feeling, a concept of what Buddhism looks like. It looks like people who are sitting very straight in those wonderful positions that I wish I could get myself into. And the Buddha’s eyes look out into space. We see ourselves doing this, and we think, “Wow that is so cool!” We have no idea what’s going on inside, but from the outside we’re looking at this going, “Oh man, that is so cool.”

So when we come to this path, we already have an idea of what it’s supposed to look like, and we play into that. Then we hear the foundational thoughts about Buddhism and the thoughts that turn the mind. Here’s the important part, “Oh, yeah, those are good reasons to do what I wanted to do already, which is to sit there like this, or to be involved in this really exotic thing, or just to be the coolest kid on the block because I read all those Buddhist books.” We all have reasons. We feel a certain affinity to it, whatever it is. I’m making it goofy so that it’s fun, but you can see and adapt what I’m saying to your own personal situation.

This is not the way it is in other cultures. The thoughts that turn the mind have to do with understanding impermanence, understanding cause and effect relationships, understanding that virtuous conduct brings excellent results of happiness and prosperity, non-virtuous conduct brings bad results of either unhappiness or being reborn in lower realms and so forth. Once we come here we think, “These are things to learn, and they are good reasons to stay on this path. So I am going to memorize them.”

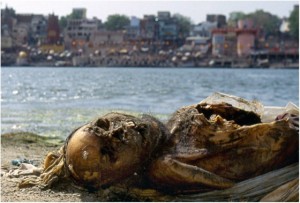

But in a society where people grow up seeing children born and their elders die before they are even able to understand the words of these teachings that turn the mind toward Dharma, where their movement through time occurs very naturally—(Nobody has a facelift in Tibet. The wrinkles just pile on, unbelievable amounts of them, because there’s no Estee Lauder. This is why I don’t live there!)—a person approaches Dharma because it does not seem reasonable to walk from birth to death with nothing in your heart, with nothing to work with. It doesn’t seem reasonable that this [movement through time] should be the main weight of your experience; that this is what you should take refuge in. Why would you do that? It’s like taking refuge in a car wreck. It’s going to hurt and it’s going to get worse.

But in our society, because we are technologically and intellectually advanced, we are not connected to the rhythms of life. So when this person who is connected to the rhythms of life, and has seen it even as a child, is told everything is impermanent in their life, this is not a big piece of information. This is not a missing piece of the puzzle. It simply organizes the thoughts for a person who has been exposed to a more natural environment, and puts words to a conceptual understanding that they already have about life. They can see there is some fun in life, some good in it, but they can also see its faults much more easily than we can in our society.

On the other hand, when we hear those thoughts that turn the mind, we have so much time invested in staying young, keeping it easy, keeping it light, making it pretty, collecting everything we’re supposed to collect, that we really have to keep that information outside of us. We can’t really let it come into us. For instance, in our society identifying with and understanding the teachings on old age, sickness and death is terrifying, because in our society the loss of youth is the loss of love. We don’t even value the wisdom that is gained in maturity enough to have it even bear mentioning.

But in other cultures, people have gone through these incredible experiences in a very natural way. They have a maturity of wisdom at the end of their life because they have seen themselves age. They have seen the beginning—the promise, the beauty, the joy. They have seen how it matures, and they have seen that you can’t take anything with you. In our society, that isn’t valued. In fact, it’s recommended that we think forever young.

Now that I’m maturing I feel, “Why would you want to do that! Young people don’t think. So to ‘think forever young,’ that’s like ‘military intelligence’!” In my experience of teaching students, I find that this is the single most dominating factor in their own dissatisfaction with their path. Why is that? Again, in our society, we learn a bunch of rules. These rules are connected to our fundamental material attitude, that collector’s attitude. In our society, we feel separated, alienated, isolated. There is a feeling of inner deadness. If you don’t know that inner deadness in yourself, then it’s deader than you think, because you can look in the eyes of anyone you know and you can see there is an inner deadness.

Now if we approach our spiritual life in the same way— by following these rules that are external because the Buddha said they’re out there, without ever viewing them in an intuitive and intimate way—we are going to go dead on our path. The path which is so precious and so unique—that amazing reality that does not arise in samsara but in fact arises from the mind of enlightenment and therefore results in the mind of enlightenment—this precious inimitable thing becomes only one more set of external rules, like a girdle that you have to wear in order to be successful, to be part of our environment.

When the path becomes bigger, which it has to do, it has to be part of your life. It isn’t something you do only twice a week. There are practices that you do every day. There are ethical situations, moral situations that you have to evaluate and look at for yourself. There is a coming to grips, a connecting with, that has to occur every minute of every day. It’s a way of life. It’s not really a church thing. Once the path becomes big like that, you find that it must influence everything about you—from offering your food before you eat it, to closing your altar before you go to bed at night, to doing your daily practice, to thinking about everything that you do and re-evaluating it. Should I kill bugs? Should I actively work towards benefitting others? Where is prejudice in my life? These are some of the issues that you have to re-evaluate.

At some point, if the path is external and you have not come into intimate touch with it, when these things start coming up, they are going to be “stuff” you have to do. They are not going to be the love of your life. They are not going to excite you. Let’s say as part of your path you have to examine one of the Buddha’s teachings, “All sentient beings are equal.” That means you have to get rid of cultural, racial, religious, gender, even species bias. All sentient beings are equal. What could be a more exciting and dynamic process than that? Wow!! Think about it! What if you really did it right, if you went inside yourself and found that place where all sentient beings are equal? What if you made it your job to really know that? What if it was something that became so moving and overwhelming that it changed every aspect of your life? What an exciting and dynamic process! How changed you would be! How much more luminous, beautiful, noble your life would be from just that one little thought.

But that’s not what we do with the Buddha’s teachings. We say, “All sentient beings are equal. Okay, I’ll memorize that. I guess that means I can’t kill anything. I guess that means that I really have to try to consider all things as equal. I guess it means I’m supposed to think that cockroaches and human beings are fundamentally equal in their nature. I really don’t think that way, but it means that I have to remember that as being one of the rules.” Rules that are outside, that you don’t take responsibility for, that you don’t connect with, are deadening. They will kill you. They are bad. Rules that you take in as pieces of information, explore deeply and know for yourself, are empowering. They give you a sense of living for the first time.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. All rights reserved