The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo called “Faults of Cyclic Existence”

In order to understand what to do, we have to understand the definition of the cessation of suffering. The cessation of suffering doesn’t happen when everything external gets all right. Can you learn this? Can we all learn this, please? If we learn this, it will change your life! The solving of this problem occurs when we are able to cut off the causes of suffering at the root. And the causes of suffering have to do with desire and the experience of duality.

So now we have to find a solution that is not anywhere in samsara. How in the world are you going to fix this? Well, you’re not… in the world. Where in the world is your solution? Guess what? Nowhere. Then we have to find something else. And what is that something else? Well, now we are looking to understand that desire and this original ideation is the cause for all suffering. So the way to cut that would be to cut it off at the root. We have to move beyond the realm of cyclic existence in order to get any satisfaction, in order to get an answer, in order to understand, literally in order to prevent the causes from manifesting. In order to cut them off at the root, we have to move outside of the realm of samsara., So we look to see if everything we’ve known and experienced arises from the idea of self-nature being inherently real. What is outside of samsara? Well, it is the one thing that, as samsaric beings, we cannot perceive. It is our own Buddha nature, the primordial wisdom nature that is the innately wakeful , sheer luminosity called Buddha.

While we are revolving in the realm of duality, we cannot see this nature. Yet it is this very nature that is the cessation of the causes of suffering.. In order to cut off suffering at the root, one would have to cut off the connection to the potency of the desire realm. We, as samsaric beings, are desire beings. We are motivated solely by desire. and the Buddha teaches us that this is the very cause of suffering. So what we’re hearing here is that everything we know, everything we call “me”, every habitual tendency, everything that has come together to knit the tapestry of our lives, is of that cause for suffering.

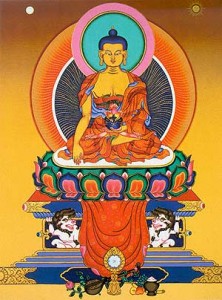

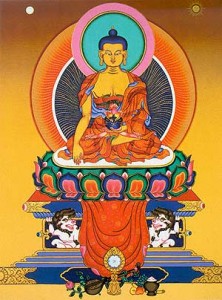

What monumental effort should happen in order to reach beyond that? How to even define what is beyond that when, by definition, we are the samsaric beings whose first assumption is that of self-nature being inherently real? This is where the power and the majesty and the potency of the practice of refuge comes into play. Because when we look at the appearance of the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha in the world, and the inner and secret refuges as well, we can see that that which we call Buddha nature, that which we call Buddha, does not originate from the desire realm. It is that ground—uncontrived, innately wakeful luminosity—that is the underlying primordial wisdom state, suchness, from which all display, all emanation actually comes.

This that we are caught in and experiencing is simply some offshoot, some manifestation in a way, whereas the fundamental all-pervasive truth of our nature, is to us unseen. Yet it is that nature, that which we are naturally, which we must strive toward in order to be awakened, That is the clue; that is the key. In our natural state as Buddha, as that sheer luminosity, there is no distinction, no distortion, no conceptualization, no idea that self is separate from other, no understanding that it could even occur that way. No distinction. Only suchness, one taste, that nature which is conditionless. As we are now we cannot even imagine a conditionless state, a conditionless nature, and yet this is our nature.

So when we practice refuge, we do it in stages. The ultimate refuge is when we understand and awaken to our own face, our own true nature. But in the beginning we practice by conceptually isolating that which is without conception. We have to. On an ordinary level, let’s say the goal was physical fitness and strength. Well, that’s an abstract concept. How do you get that? You can’t buy that. You can’t hold that in your hand, but you can do the exercises, you see? Same thing. Buddhahood. We can’t buy it, we can’t hold it in our hand, but we can establish the method.

The method begins with the recognition of the Buddha which is the primordial, uncontrived nature that happens to have appeared in cyclic existence at this time, during this aeon, as a man. But the man is not the thing. Lord Buddha is the display of that nature. We use his image and his teachings as a way to understand because he speaks directly from that nature. But we understand that we are awakening, awakening, awakening. That’s the understanding of refuge. We are looking for that which is not composed of the causes of suffering. And here while we are suffering and revolving endlessly, and watching others revolve endlessly, here while this occurs, we are that, in truth, which is the cessation of suffering, Buddhahood.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved