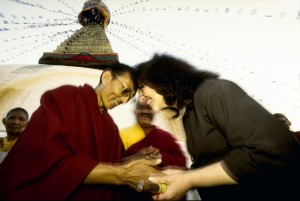

The following is an excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo offered during a Phowa retreat:

Those people who accuse Buddhists of creating a kind of depression or melancholy through these ideas, are, what I would call, in denial. They’re simply in denial. They’re not at that stage of maturity, either in their physical lives or in their spiritual lives, where they can come to grips with this idea [preparing for death]. Some of it has to do with their age. Look around you. Look at the age of the people in this room. There are very few of us who are in our twenties. There are a few of us who are in our thirties. Most of us are at least kicking down the door of forty, if not on the other side. And it’s not because forty-year-olds are so much more spiritually developed than twenty-year-olds. Even the forty-year-olds that are spiritually developed have to be twenty at some point, so that can’t be it. But there are certain changes that happen psychologically within the context of our lives.

Many of you have already noticed this. This is not a news flash, is it? One of them is that we meet a stage in our life where we have a recognition, and the recognition is keyed off by, first of all, physical changes within our body. It is obvious that things are changing. We look in a mirror. Then we look at a picture of us a decade ago. And even a twenty-year-old could see this. You have changed. Maybe a twenty-year-old could see it even more dramatically. If you are twenty-five now and ten years ago you were fifteen, you’re much different now than you were back then. But how much more so for the forty- or fifty-year-old who looks at their twenty-year-old pictures. I’ve got a couple of them sitting on one of the shelves in my room. One of my sons was thoughtful enough to give me these pictures framed—framed, mind you—so I can look at them every day! They’re sitting on my shelf, and I look at myself when I was in my twenties every day. What a great technique for a Buddhist! And I’ll tell you, things have definitely changed.

So those of us who are going through those sorts of changes and we’re seeing ourselves on the downside of that midlife experience, we’re also having another kind of expansion or understanding that is coming to us for the first time, not because we weren’t capable of seeing it for the first time, but because we are suddenly keyed in by certain kinds of visual stimuli and also we’re keyed in by what’s happening inside of us. Somewhere in that first five years of our forties we come up with a realization that is a little hard to take, and that realization is that it is not likely that we have a full half of our lives left. It is not likely. It is more likely that I am more than half done with my life. That’s what I’m thinking about, and that’s what you’re reminded of when you look at those pictures of yourself when you were younger. And I’m thinking of how none of us has ever gotten used to that.

Do you remember, let’s say, when you were going to school, especially if you hated school like many people did, or perhaps going to a job that you didn’t like when you were literally owned by somebody else from, say, nine to five, or eight to three, or whatever it was, during five days of your week? You look forward to the weekend as though it were manna from heaven, or nirvana. Or perhaps equally as important as enlightenment. In fact, at a certain age and a certain stage, right about oh, Thursday afternoon, if someone asked you if you wanted your weekend or nirvana, you might have taken your weekend. Weekend becomes out of proportion in terms of its importance, because we have a hard time dealing with the stress of an entire period of time when we look forward to the rest. Do you remember how it felt on Friday night when you were really young? Party time! Friday night is happy time, and no matter what you did it was really fun. You made sure you went out. Friday night was definitely the night that you did something, because you had some steam to work off and it was the first day of the weekend and you were really excited. And then you go all the way through your weekend, and of course there’s the Saturday morning recovery for some of us. And then later on there’s the Saturday evening. And towards the end of the evening, you remember that kind of sinking feeling in your stomach when you realize that tomorrow was Sunday and there was only one day left? Not only that, but Saturday night was the last night that you had before the night before you had to wake up early again. You know, that kind of thinking.

So that’s the kind of minds that we are preparing for our death with. You think about that: It’s the same mind that we deal with our life situation with. We get away with it as long as we can get away with it. So long as it is Friday night and Saturday morning and Saturday afternoon and just starting Saturday night, we’re getting away with it. We are in denial about everything else. We’ve pushed aside anything that is uncomfortable or frightening to us, or anything that is stressful. And the way that we’re dealing with stress at that particular moment is to be who my son calls ‘Cleopatra, Queen of Denial.’ That’s his joke. So we’re Cleopatra throughout most of our lives. And then suddenly you hit forty-five and it’s Saturday night again. It is. Forty-five, it’s Saturday night. Because at forty-five you start to want to go to bed a little earlier, and you can’t help but get up earlier, because you wake up at that time. You’re not like you used to be and you can’t go back to sleep. And all sorts of things change. But suddenly at that time, as well, you realize that your weekend is more than half over. Or your lifespan, in this case, is more than half over. And it begins to wake you up and causes you to relate to necessity. Reality is hitting us, and that’s what’s happening. And for some us that is a very sad part of our lives, and there are many different reasons for that.

This isn’t really a part of our Phowa retreat but I would like to mention it anyway.

There are many people who literally cannot get themselves together at this point in their lives because they are too scared, too much in denial about the passage that is overtaking them right now. There are many people who have spent their whole lives seeing their own self worth and their own value according to their looks, their youthfulness, their beauty, their sexuality, their youthful vim and vigor, their kind of youthful energies, determination. There are so many people who strongly take all of their ideas about self worth in accordance with their ideas about desirability. And, of course, here in America we have a cult associated with youth going on. A youth cult. Women are only attractive in their twenties; they’re barely attractive in their thirties if they can make up well; and in their forties they’re going over the hill. That is the popular Madison Avenue approach.

Of course, nowadays we are finding our self worth in a different way, and fortunately women are seeing themselves as something other than a desirable object. Men are seeing themselves as other than a warrior that has to prove his prowess at every turn. So fortunately we’re not viewing ourselves in the same way, but we still seem to maintain this denial about our lifespan. We do have this denial about our lifespans. And even those people who are in their fifties and going on to their sixties… Once again, when we move into our sixties there are no guarantees. There are plenty of people who die in their sixties. Plenty of people. Even though we feel well, even though we feel fairly youthful in our sixties—and I hope you do, I hope I do when I reach my sixties—still there is no guarantee. But we don’t think like that. We think, “I’m feeling well now. Everything’s fine.” And there are many people who don’t plan for their death, even in terms of making out a will. They don’t plan at all for these events during the course of their lives, except when they get to the very, very end and it’s literally impossible to be in denial about this thing.

So you wonder, are these the sensible people, the people who are in denial like that, that are not preparing themselves for their eventual continuation though samsara? Are they wise? Are they free of the obscuration of ignorance? Not for my money. I think they are the most ignorant; they are not preparing. It’s like knowing that you’re going to have an extraordinarily challenging and difficult tomorrow, where if you knew that if you spent the afternoon and the evening preparing for tomorrow, maybe reading this book or studying a bit or getting your props together that you need for a certain presentation, it could easily be that while tomorrow would be stringent and challenging and you would definitely be tired afterwards, it could be the kind of thing where you feel like a job well done. Good for me. I worked really hard but I was prepared and I got the job well done. You could handle it that way. Or about your difficult tomorrow, you can of course think, “Tomorrow is tomorrow, today is today and I don’t have to worry about it until tomorrow, do II don’t have to think about it this afternoon because it’s not tomorrow yet.” See, you’re doing this kind of ‘dzogchen-esque’ double talk. When it’s dzogchen-esque double talk from a sentient being rather than true dzogchen teaching from a lama, it’s not going to be quite sensible, is it? It’s not going to be the same at all. So the idea that ‘today is today and tomorrow is tomorrow and never the twain shall meet’, and the idea that ‘well, we should just kind of go with the flow, have another avocado, think about tomorrow when tomorrow comes’, is not the kind of thinking that is going to help you feel strong and powerful the next day. And probably what will happen the next day is that you may fail, or the chances are that you won’t do such a good job, and you definitely will not have the result that you expected or desired from your efforts during that day. And it’s because of a lack of preparation.

Now the very people who would advise you to simply let it be and think positive thoughts and have a good time and ‘don’t worry about it ‘til tomorrow,’ have the same kind of mentality that says that Buddhism is a depressing and melancholy sort of idea. These are the people that are in the state, within their own minds, of ignorance and delusion and denial, where they aren’t considering things from the intelligent, common sensical, wisdom point of view. They’re not facing the fact that tomorrow will come. There is no way to get out of dying. Absolutely none. You can’t even die to get out of dying. There’s just no way to get out of it. And we will face this, and how much better is it to be prepared. Because I tell you that while death is something that is extremely difficult to do well, and requires intelligence, forethought, and of course practice, it can be done well, in the same way that you can prepare well for something that you have to do; and you can ace it.

Now you have to ask yourself what is your habit about such things. Are you accustomed to failure? Some people are, you know. Some people fail habitually. There is a strong element of neuroses in the way that their minds work. They are, according to other people who are close to them and seeing them, sometimes called ‘programmed for failure.’ They’re sometimes called extremely neurotic. They put obstacles in front of themselves and cause themselves to fail. And they mostly do this with their attitudes. Sometimes I’m teaching class and I look around. I watch your faces and I perceive the energy that is coming from you and I think, “Problem. You’re going to fail.” Not that I’m predicting your demise and not that I’m wanting you to fail. It’s not that. But it’s obvious, from the attitude, from the way that you are listening, from the barriers that you are throwing up, within your own mind, in front of yourself, that you are not going to let yourself do well.

Copyright © Jetsunma Ahkon Norbu Lhamo All rights reserved