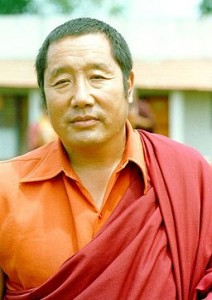

An excerpt from a teaching by Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo

I never cease being surprised when someone is personally challenged by my path, especially since I never try to convert them. I don’t understand why it should bother one person what religion another person practices. Or how one person can take it as a personal threat when someone else doesn’t believe in their god. I cannot for the life of me see where unity argues with diversity. In fact, I think that a lot of the world’s problems, at least from the relative point of view, arise because people have no tolerance for one another.

Since I have listened to many people describe to me their heartfelt feelings about what it was like for them when I chose Buddhism, I would now like to tell you how it was for me when I chose Buddhism. I think turnabout is fair play.

First of all, from my perception, there was never any conversion process. There was never a time when I converted from something else to Buddhism. The reason why is that since the time of my adulthood, I have never formally identified with any religion. There was never a time that I felt that I was going to an external god; and yet I have a very spiritual and religious sense of there being a goal, a path and a reality that is absolute or true. And I knew that that reality had no describable nature, that that reality was essentially free of all conceptualization, that that reality wasn’t a reality in a sense, because reality implies thingness. I knew that there was something that was beyond; and that beyondness was free of any ideas of here or there, or high or low, or self or other. It was free of any contrivance

I didn’t use the word emptiness at first because I didn’t know the word, but I used to think of it as being vibrationally zero. That is to say, there was no artificial construction within it, no contrivance, no conceptualization. I knew that any conceptualization or idea that one had was delusion. And I knew that there was an awakened state in which one realized one’s nature, and that nature was essentially free of all limitation. That nature is not separate, it is not other; it is not something that one must go to or even progress toward. That nature is the true nature, and one needs to awaken to it, and that awakening occurs naturally.

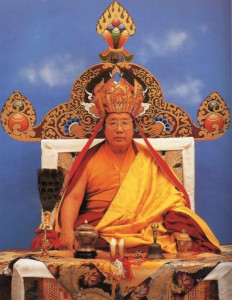

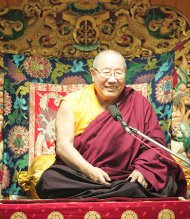

In order to describe that philosophy, at first I had to use general metaphysical terms. There were no other terms for me. I never had anything to do with Buddhism. I had never even read a book about Buddhism. When I met His Holiness Penor Rinpoche and I began to hear about the Buddha’s teachings, my sense was not of changing at all. Nothing of the Buddha’s teaching seemed strange to me. From the deepest part of my heart, I felt that I had come home. My sense was, “At last, here’s the vocabulary I’ve been looking for. Here are the words that I’ve needed all this time to describe what I’ve been trying to teach.” And so gradually I began to absorb and introduce the vocabulary into my teaching, because I already had students at that time.

Now Penor Rinpoche says that I’m an incarnation of somebody that used to be Tibetan 400 years ago. I don’t really know if that’s true or not. If Penor Rinpoche says what he says, then that is due to his wisdom and his kindness, and I can’t take any credit for that; and I have nothing to do with it, other than that I rely on it. I feel like I am just an ordinary person and I’m doing my best. I believe in the Buddha’s teaching. I believe that compassion will save the world. I believe that enlightenment is the end of suffering. That’s what I know.

So I’m not going to pull an ego trip and say, “Oh, when I heard the Buddha’s teaching, I recognized it, I knew it, I remembered it,” in some hokey way. I’m not going to say to you, “Oh, immediately upon hearing the Buddha’s teaching I came into my own, and therefore I knew all these amazing things.” It wasn’t like that at all. It was something like the joy you might feel if you recognized music that had been in your heart for a long time being played on the radio. There was a part of me that could recognize this truth as being truth. It wasn’t really a change. It was more like finding the right suit of clothing for my size. So if any of you are uncomfortable with the fact that I’ve changed, please don’t be; I’m certainly not. I’ve always been a Buddhist. I just didn’t have the words.

Now, I would like to tell you a little bit about what I felt in my heart when I found the Buddha’s teaching. I felt humbled to have the opportunity to practice a path that has been around for more that two and a half millennia and that has brought people to enlightenment again and again and again. Ordinary sentient beings, through the intensity of their devotion and their practice, have achieved not theoretical, but exacting, reportable and repeatable physical and psychic signs that indicate enlightenment, such as bodies producing relics at the time of death and other miraculous signs. This has happened again and again and again to guys like you and me.

Sometimes I stop and I think, “What can I have possibly done to have this opportunity? What good fortune has befallen me? What circumstances have come together over ages and ages of time to give me this chance to practice a path that really works and has worked again and again and again?”

I am awestruck that I don’t have to follow someone’s advice who is not enlightened, because I am following the Buddha’s teaching. The Buddha knows what he’s talking about because it brought him to the state of supreme realization, and it has produced enlightenment in so many beings.

© Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo