Buddha taught that one of the most heinous crimes one can commit from the spiritual point of view is to proclaim oneself to be more advanced or spiritually competent than is actually the case. Why that is is a very involved subject, but to understand it is to better understand spiritual fidelity.

According to the Buddha’s teaching, cyclic existence is unbearable because it is pervaded with suffering. Even the happiness that there is within cyclic existence is temporary. And so we suffer from impermanence and cling to all manner of experiences. This fixation on maintaining a permanent, continuing ego-self in order to feel safe causes all suffering. According to the Buddha, self-nature is not inherently real. Our true nature is the primordial wisdom state, which is free of all conceptualization, including the perception of self-nature. It is clear, luminous and innately wakeful. It is not empty and dark in the way we would think of nothingness, but it is simply aware with a non-specific awareness or wakefulness. This is our nature — not the ego-self that we conceive ourselves to be.

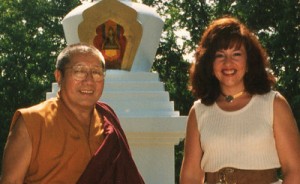

According to this view, there is no being who is greater than another. Even in the case of lamas who sit on thrones giving spiritual teachings, if they are truly realized, they do not consider themselves to be greater beings than anyone else. In fact, their realization comes from realizing the sameness of all phenomena and the equality of all that lives. Thus to think of oneself as being more advanced or greater than others is a falsehood. Yet many people do have this idea. And when they come here, they say, “You must know who I am and why I’m here. I know I have a special mission.” People have even written to me from across the country, asking me to recognize them as a tulku. In the first place, I don’t have the authority to recognize anyone. And even if I did, I would never recognize someone who asked for it. Never. In fact, I would pay the least attention to such a person.

Why? According to the Buddha, the goal is not to become a greater or vaster ego. The goal is to realize the primordial wisdom state, which is the same inherent nature in all sentient beings. Anything that we build on top of that is false and actually takes us in exactly the opposite direction from the Buddha’s teaching. True nature is innate. It cannot be grown. It will never be bigger or smaller than it is now. It will never change, and therefore it cannot be manipulated.

So when people come here feeling that they have an honored place or a special mission, they are only contributing to the size and rigidity of their egos, and they must simply wait it out. As a woman I know in Tennessee once said, “If it doesn’t come out in the wash, it will in the rinse.” What you’re going to do, you’re going to do. And if it is in accordance with the Buddha’s teaching, you will achieve realization.

The Mahayana path cultivates the desire to benefit beings and eventually leads out of the very self-absorption that causes the desire for special recognition. Consider yourself merely a function of the Buddha’s kindness. If you are transforming your life into being a vehicle by which sentient beings are benefitted, you really can’t be concentrating on the idea that “I’m helping you,” because then the “I” will become very inflated and the “you” will become dependent. To prevent such obstacles, we must think about the inherent equality of all that lives — although our egos have various appearances, our nature is the same. Thus we are completely equal, and anything but kindness is a waste of time.

According to the Buddha, we should apply the antidotes that purify our mindstream and perception and lead to enlightenment. What are those things? They are the things that we call meritorious activity: generosity, recitation, contemplation, meditation, prayer, offering, studying and teaching. Over time, these activities will loosen the mind’s tight fixation on ego and one will spontaneously view the natural state. Ultimately one will remain stable in that state, awake as the Buddha is awake.

The Buddha never said, “I am God.” Nor did he say, “I am the Son of God.” Or even, “I am here to help you.” All he said was, “I am awake.” Our job is to awaken to our true nature, and that is what we do. Quickly? Probably not, although with diligent practice, the Vajrayana vehicle can lead to enlightenment in one lifetime, or three, or seven.

Each of us walks through the door of liberation alone. Each of us is absolutely responsible for our own awakening. So to come to a teacher and say, “Please recognize me,” or “Please enlighten me,” is a little silly. One should be humble. One should study. One should practice. And however long it takes is however long it takes.

Students come to me and they ask to know the secret of the universe. Here is the secret of the universe: work hard. There is no other secret. To attain the precious awakening one should purify the mindstream; one should make one’s life a vehicle for generosity.

Always think more of the welfare of others than your own. Be honest. Be courageous. Look yourself square in the eye and get the big picture. All sentient beings are the same. They are equal. There are no special cases. All of us must cease this fixation on self-absorption in order to realize the natural state.

There is no excuse for not starting now. If you think you’re not ready, get ready. No one is ready. If you think you’re not kind, get kind. It’s a discipline to think of something greater than one’s own self-absorption. Start small, with 10 seconds of pure generosity, caring only for the welfare of others. When you get 10 seconds, move on to 12. In a couple of weeks, try 30 seconds. Then go for a minute; that’s a year’s worth of work. Pretty soon you’ll be thinking an hour. And after a while it will become a habitual tendency.

If you find yourself backsliding, don’t be surprised. That’s the nature of samsaric existence. Be patient with yourself; do the best you can, give yourself a break and don’t let yourself get away with murder. Those are my three cardinal rules for following the Path.

In closing, let me connect this with spiritual fidelity. One is true to oneself when one is honest, when one faces that one is a samsaric being involved in cyclic existence and is no longer shocked or ashamed or surprised at that. So it is. This is where we start. But you should start with honesty, courage and responsibility. You are responsible for the humility that you have within your mind, the honesty and devotion you have toward the Three Precious Jewels, which are the very display of enlightenment itself. Apply discipline and work hard. Be worthy and be true. This is spiritual fidelity.

©Jetsunma Ahkön Lhamo