[Adapted from an oral commentary given by His Holiness Penor Rinpoche in conjunction with a ceremony wherein he bestowed the bodhisattva vow upon a gathering of disciples at Namdroling in Bozeman, Montana, November 1999. —Ed.]

In general, dharma consists of many divisions and distinctions of spiritual teachings, while at the same time the nature of all dharma is that it has the potential to liberate beings, both temporarily and ultimately, from the suffering of cyclic existence. The main cause or seed for that [liberation] is the cultivation of bodhicitta. Various traditions exist for the bodhisattva vow ritual and training. The lineage for these particular teachings, which was passed from Nagarjuna to Shantideva, is known as the tradition of the Middle Way as well as the lineage of the bodhisattvas.

There are four aspects related to receiving the bodhisattva vow: receiving the vow itself, ensuring that the vow does not degenerate, repairing the vow if it is damaged, and methods for continuing to cultivate and maintain the vow.

The first aspect of receiving the vow itself has three aspects: the individual from whom one receives the vow, oneself as a qualified recipient, and the ritual for receiving the vow.

First, the individual from whom one receives the vow must have strong faith in the Mahayana vehicle and must be a true upholder of the vow. He or she must be someone within whom the vow abides and should also be someone who is very learned concerning the vehicles, particularly concerning bodhisattva training. Such a person must never abandon bodhicitta and must always keep the vows pure, even at the cost of his or her own life. That individual must also be a practitioner of the six paramitas of generosity, morality, patience, diligence, meditation, and prajna, and must never engage in any activity that contradicts them.

According to the tradition of Nagarjuna, the way to receive the vow for the first time is from a spiritual guide. Later, if an individual’s vows[1] degenerate, and if a spiritual guide is then absent, that person can restore the vows in the presence of an image of the Buddha. It is not necessary that they be restored in the presence of a spiritual guide.

The second aspect for receiving the vow itself concerns the individual who qualifies to receive it. According to the tradition of Nagarjuna, all sentient beings who desire to receive the bodhisattva vow qualify to receive it. The only exception is types of gods in the formless realm, called gods devoid of recognition, which are gods that lack cognitive abilities. With this one exception, basically all sentient beings qualify to receive the vow. But those who qualify in particular are those who have supreme knowledge, which refers to those who know what the bodhisattva vow is and what the benefits of receiving and maintaining it are. Such individuals are particularly worthy recipients because they have profound compassion and are able to use that compassion to bring both temporal and ultimate benefit to other beings. In short, any individual who has an altruistic attitude and wishes to take the bodhisattva vow qualifies to receive it.

The ritual [which is the third aspect of receiving the vow itself] also has three parts: the preliminaries, the actual ritual, and the concluding dedication. The preliminaries have four parts: adjusting one’s own intention, supplicating the objects that confer the vow, taking the support of refuge, and practicing the method of accumulating merit.

First [during the preliminaries] one adjusts one’s intention [in order] to be in harmony with the special feature of this instruction. There are three ways to do so: by developing repulsion or weariness toward the suffering of samsara, by developing an attraction to enlightenment, and by transcending the two extremes of samsara and enlightenment through vowing to maintain the middle way.

When considering the first step to adjust the mind, one cultivates repulsion and weariness toward samsara as antidotes for strong attraction to worldliness, to ordinary phenomena, to one’s own life, wealth and endowments, and to one’s friends and loved ones. Through cultivating weariness toward the suffering of samsara, we learn about impermanence and come to understand the impermanence of all worldly phenomena.

[The second way to adjust one’s intention in order to be in harmony with the special feature of this instruction is through] developing attraction to enlightenment. According to this tradition, what leads one to develop an attraction to enlightenment is the cultivation of love for all beings, which one begins by contemplating the suffering of cyclic existence and then cultivating repulsion and weariness [toward that existence].

This leads to the third stage concerning the aspect of adjusting one’s intention [which is the first of four aspects of the preliminaries to the ritual for receiving the vow]; transcending the two extremes of samsara and enlightenment by vowing to maintain the middle way. The practice of the enlightened mind, bodhicitta, involves two levels, the aspirational and the practical. Maybe now you’re thinking, “If we reject the suffering of the three realms of existence and avoid attraction to the quiescence of the hearers and solitary realizers, what is there for us to obtain? What we are to obtain is the state of bodhisattvahood, which is dependent on bodhicitta cultivated for the sake of self and others. It is only bodhicitta that leads beings from the suffering of existence to the state of fully enlightened buddhahood. We must avoid the two extremes: the quiescence of ordinary nirvana and the endless cycle of samsara. It is only through cultivating bodhicitta that we can truly follow the middle way.

Through cultivating bodhicitta you will purify all nonvirtue accumulated in the past, present, and future, and compassion and all noble qualities, including the ability to meditate in Samadhi, will blossom in your mind. As you dedicate yourself to the welfare of others, the [strength of your] vow will increase to the point where you are truly able to help sentient beings as limitless as space. You will be able to bring limitless beings to enlightenment, until the ocean of existence is emptied. The Buddha taught that without the cultivation of the precious bodhicitta, there is no chance to achieve the state of fully enlightened buddhahood. Therefore, for the purpose of all other living beings, with great enthusiastic joy you should give rise to the precious bodhicitta and engage in the actual practice.

Having adjusted your intention [in order] to begin the actual practice, supplicate the objects from which you will receive the vow. Recognizing the spiritual teacher to be the Buddha, first offer the mandala to receive the bodhisattva vow. Then repeat the supplication to the spiritual teacher and request to be a recipient suited to receive the vow and to accomplish the training for the benefit and welfare of all living beings.

Next, go for refuge in the sublime supports: the Buddha as the embodiment of the three kayas, the dharma as the representation of all scriptural transmissions and realization, and the Sangha as those who have attained the irreversible path of the sublime ones. From this moment until enlightenment, in order to liberate all parent sentient beings from their suffering, develop compassion. Realize that [in order] to accomplish your goal, aside from reliance on the Three Jewels of Refuge, there is no other support for refuge. It would be impossible for you to bring all beings to liberation without the buddha, dharma, and sangha. With irreversible faith and devotion, repeat the vows of refuge.

According to the Mahayana path, we take refuge in the teacher who shows us the path to liberation: that is the buddha. We engage on the path of Mahayana practice by cultivating the precious bodhicitta until we realize buddhahood: that is the dharma. The sangha is the spiritual community that is on the same path as we are on, assisting in the accomplishment of our mutual goals.

Next is the method for accumulating merit. Visualize in the space in front a magnificent throne supported by eight lions, where your teacher sits, indivisible with Lord Buddha Shakyamuni. The eight arhats and a vast assembly of buddhas and bodhisattvas surround him like masses of clouds that fill the ten directions. Imagine countless emanations of yourself filling the entire pure realm of your environment, which includes the entire universe. You and countless emanations of yourself and all parent sentient beings join together to fill [all of] space. With humility, reverence, and faith, you and they all bow down and pay homage to the objects of refuge in the space in front. [Here you] prostrate by touching the five places of your body to the ground. This is the branch of prostration, a powerful antidote for pride. Having pride means having the attitude of cherishing yourself by thinking you are so great and special. Performing prostrations purifies that egotistic attitude.

Now visualize that you and innumerable emanations of yourself present boundless offerings. Offer all of your wealth and endowments, including the root of all virtue in this lifetime, in all your past lifetimes, and in future lifetimes. Offer objects that are of this world and those that are transcendent. Imagine them to be inconceivable vast clouds of outer, inner, and secret offerings that completely fill space. In addition, offer the essential nature of reality.

The next branch involves [making] confession.

The next branch concerns rejoicing.

The next branch is that of requesting the buddhas to turn the dharma wheel.

Next is the branch of requesting the buddhas and bodhisattvas not to pass into nirvana.

The final branch of the seven entails the dedicating of merit. Amass all merit, especially the merit of reciting these seven, as well as all virtue and merit of the three times, and offer it for the welfare and liberation of all parent sentient beings. [The practice of] dedicating merit is the antidote for having many degrees or levels of doubt.

The second aspect related to the ritual is that of bestowing the vow, which has two parts: training the mind and receiving the vow. To train the mind, one begins by thinking of all parent sentient beings that have remained in cyclic existence from time immemorial until now and that have been extremely kind as one’s own parents in the past. Consider how they suffer unceasingly. Then think, “In order to alleviate the suffering of all these beings, I will give myself, my life, my wealth, and my endowments, and without ever giving up, I will work unceasingly to free sentient beings from suffering. I will happily take upon myself whatever suffering they are enduring.”

The actual bestowal of the vow follows.

Begin the stages of training by establishing the three moralities. The first morality, which is the basic morality of bodhisattva training, is to abstain from harming others. The second morality is to practice to amass great virtue, which means constantly practicing the six paramitas of generosity, morality, patience, diligence, meditation, and the wisdom of knowing the nature of emptiness. The third morality is to accomplish the purpose of others, which means directing all effort and actions toward the sole purpose of repaying the kindness of parent sentient beings and establishing them in the state of fully perfected buddhahood. Keeping all this in mind, you take the vow.

When you recite the verses of the vow, you should be in the state of the three recognitions. The first recognition is to have strong faith and devotion in the gurus, buddhas, and bodhisattvas because of knowing their noble qualities. The buddhas and bodhisattvas possess omniscient knowledge concerning the details of the relative lives of all sentient beings. Not an instant goes by where they do not simultaneously know the nature of all phenomena. The second recognition is to have tremendous compassion for all parent sentient beings, to feel completely responsible for repaying their kindness, based on all the reasons explained earlier. The third recognition is to work unceasingly and tirelessly to establish all parent sentient beings in the state of fully perfected buddhahood.

To take the vow, kneel, press your palms together, and feel certain that the buddhas and bodhisattvas of the ten directions abide in the space in front of you. Give rise to the three recognitions. With strong, fervent regard and the aspiration to accomplish your vow, recite the verses of the vow. When you complete the third recitation, feel certain that you have received the bodhisattva vow.

Upon receiving the vow, you should rejoice. Consider that you have taken countless rebirths with innumerable bodies, and that not until now, in this present rebirth, have you had the opportunity to really cultivate the enlightened mind with the vow to guide all beings to liberation. With that in mind, rejoice in taking this vow, and feel you have finally extracted the purpose of your human life.

The following are the concluding stages of dedication [the third and final aspect of the ritual itself]: To begin, consider the benefits of taking the bodhisattva vow. Although the benefits are so vast they cannot be enumerated, a few of them will be mentioned here. When cultivating bodhicitta and taking the bodhisattva vow, you are elevated from the rank of an ordinary individual to become a son or a daughter of the bodhisattvas. Now you are an object of homage for gods and ordinary human beings.

Even though you [may] lose mindfulness, if you never lose the bodhisattva vow, the force of bodhicitta will always bring you back to your original vow. The more you become accustomed to the bodhisattva vow, [the more] your negative tendencies and habits will be transformed and absorbed into the continuum of bodhisattva training.

The four stages involved in receiving the bodhisattva vow include receiving the vow, maintaining the vow, practicing the six paramitas, and achieving equanimity, which means purifying the mind from partiality or attachment and aversion. With these four stages [complete], the noble qualities and benefits are ineffable.

These few points provide a very brief, highly synthesized enumeration of the benefits of the bodhisattva vow, benefits that are otherwise inconceivable and inexpressible. If we tried to express any form these benefits could be likened to, even the sky would be unable to contain that.

Keeping all that in mind, recite the verses of rejoicing in your personal good fortune, followed by the verses of others rejoicing with you. Invite all beings to be present, including all the buddhas and bodhisattvas, and ask them to bear witness as your guests on this occasion of receiving the bodhisattva vow. As you recite the verses, think that all beings rejoice along with you.

Once you receive the vow, you must know how to guard it from deteriorating. This brings us to the teaching on how to ensure that the vow does not degenerate, which involves the three things to know—namely, how to keep the vow, how to train, and how to stop external forces and circumstances that may hinder you in your ability to keep the vow.

First, the instruction on how to keep the vow concerns the cultivation of aspirational bodhicitta and the training in practical bodhicitta.

The second part concerning how to keep the vow involves the training in practical bodhicitta. Here you must reject the two categories of downfalls, which are the root and branch downfalls. Those are downfalls that can occur within the context of the various categories of vows one takes. For example, there are five root downfalls that pertain to rulers, five to ministers, and five to beginners. There are also vows for those who practice on a common level. Any individual who has taken the bodhisattva vow is capable of committing a downfall. However, these instructions do not pertain to any individuals who had a mental impairment or deficiency or were unconscious and therefore didn’t know what they were doing when they took the vow.

Next is the discussion on how to repair the vow if it degenerates and how to continuously cultivate and maintain the vow. [This is the third of the four main aspects related to receiving the vow.] The three ways that a vow deteriorates are by losing the foundation for the aspirational mind, through rejecting the vows by returning them, and by allowing a root downfall to occur. In the first and second cases, the vow is completely lost and must be taken again in order to be restored. In the third case, if you commit a root downfall, you must confess it immediately. If you postpone [your] confession of a downfall, that downfall will become more and more difficult to purify. Apply the four powers, and in the presence of the Three Jewels of refuge, confess your downfall. Pray to purify any negativity accumulated through the downfall, and then perform purification practices.

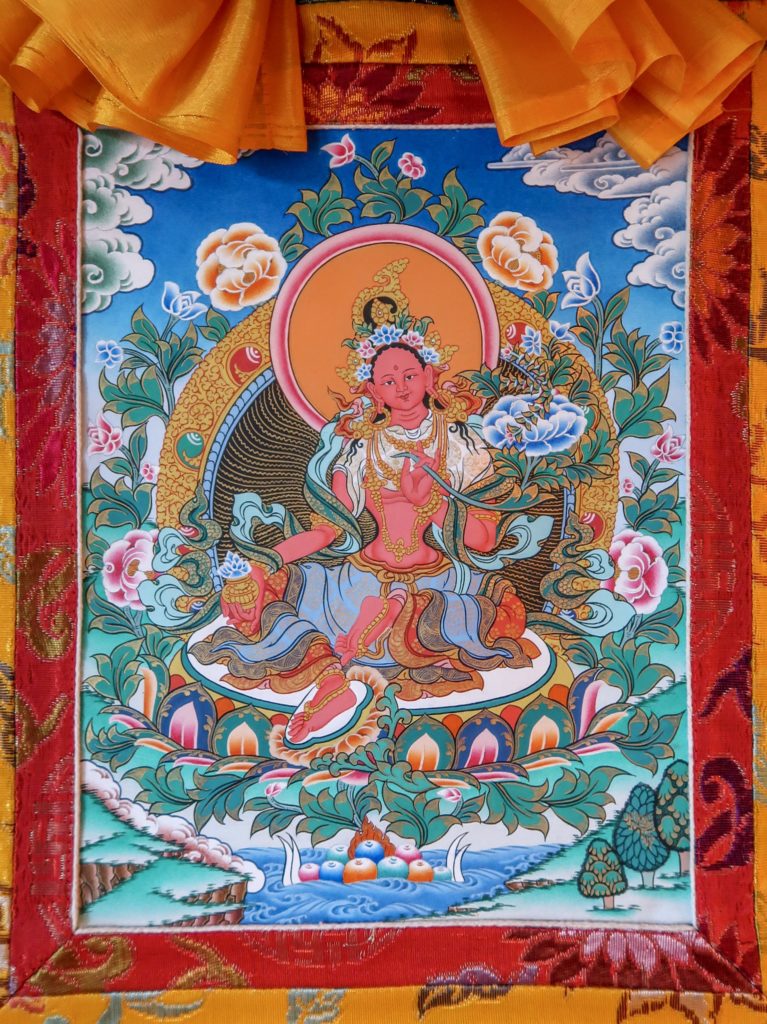

Once you have received the bodhisattva vow, you may take it again either if you have lost it or [in order] to ensure that it does not diminish. To retake the vow on your own, consider that you are in the presence of the buddhas and bodhisattvas. With strong faith and devotion, feeling they are present, take the bodhisattva vow directly from them. Otherwise, you can use a support of the Buddha, such as a statue for enlightened form, a scripture for enlightened speech, or a stupa for enlightened mind. If you do not have any of these supports, you can use the power of your own mind in order to take the vow.

The reason we retake the bodhisattva vow is because we are habituated with the five passions. We always do the opposite of what should be done. We always turn things into negativity. The little bud of our buddha nature, which is just beginning to open, should blossom when exposed to the blessings of the sun and the refreshing showers of dharma. Instead, it dries and closes due to [our] negative habits that obscure the circumstantial blessings that come through the dharma. If we encourage ourselves by continuously reaffirming pure intentions and by taking the bodhisattva vow over and over again, that will give us the power and strength to rise up despite all the difficulties imposed by the influence of our passions. Then, by focusing on the vow and training, we will obtain the confidence to abandon self-concerned fixations. Emphasis shifts from the self to the needs of others. Once our bodhisattva vows become strong, accomplishing whatever prayers or aspirations we hold in our hearts will be very easy.

The three dharmas to adopt are to rely on a spiritual teacher, to make offerings to the Three Jewels, and to never abandon compassion for any sentient being. The first of the four recognitions to accept is to examine yourself to see whether you have the potential to uphold the vow and to maintain the training. The second is to examine to see whether an action is virtuous or not. If you determine it to be virtuous and fail to accomplish it, or if you contradict it or remain indifferent, then in all three of these cases there will be a downfall.

[Third,] in order to constantly guard the vow, you must be learned in the teachings on bodhisattva practice as found in the scriptures, particularly those [teachings] that discuss the subject of cultivating bodhicitta. [Fourth,] you must know how to be conscientious and mindful, so that [your] bodhisattva training will not deteriorate. If your training is free from deterioration, that indicates you are practicing mindfulness.

Although there are countless ways of knowing how to guard the vow to ensure that it will not be lost, they can be synthesized into three. First, the bodhisattva training must be internalized as much as possible. Second, the internal training must be expressed externally to meet the needs of beings by bringing them the gift of dharma. Finally, there must be the pure view of the pure lands of the buddhas. From now on, at all times and in all situations, with loving-kindness and compassion, you must do your best to always be of benefit to all sentient beings equally. No matter what, you must never abandon any living being for any reason. In addition, you must never be biased towards some and against others. From this time forward you must consider all beings impartially and with loving-kindness and compassion, and you must do your best to always increase your virtuous deeds, which you dedicate to the service and benefit of others. This is how you will be able to keep your bodhisattva vow.

It is especially important to always cultivate mindfulness. Once you have taken the bodhisattva vow, if you are mindful of it, then you won’t forget to direct your every effort toward the practice of dharma. It is also important to cultivate conscientiousness, which will stabilize your ability to be mindful. Finally, it is important to be careful in all the different circumstances of life. Mindfulness, conscientiousness, and care are extremely important.

[Once you have taken it] you will have the bodhisattva vow in your mind. You will no longer be an ordinary world individual, as you will have entered the path of the bodhisattvas to become a son or daughter of the buddhas. If you keep your bodhisattva vow, without allowing it to degenerate, then you are truly a bodhisattva. If you drink a cup of water from the ocean, you can say that you drank the ocean; likewise, if you enter the path of the bodhisattvas, you can say that you are a bodhisattva. With faith and devotion, please do your best to keep this vow.

The Bodhisattva Vow

Dedication Prayers

[1] [While the word in the term bodhisattva vow is commonly used in its singular form, it is also often used in its plural form, bodhisattva vows. Both the singular and plural forms of the term in fact represent a series of vows. Readers will find both forms used throughout the commentary.—Ed.]

From “THE PATH of the Bodhisattva: A Collection of the Thirty-Seven Practices of a Bodhisattva and Related Prayers” with a commentary by Kyabje Pema Norbu Rinpoche on the Prayer for Excellent Conduct

Compiled under the direction of Venerable Gyatrul Rinpoche Vimala Publishing 2008